Somebody's Heart Is Burning (13 page)

I looked up in surprise.

“I guess it depends what you mean by culture, Nadhiri,” I said carefully. “Obviously the U.S. is a blend of many cultures. But if you define culture in terms of a common mythology, common symbols—”

“What is an American?” she asked suddenly.

“What do you mean?” asked Katie, after a short silence.

“What do you think of, when you think of the word ‘America’?”

The condescension in her voice irked me, and I answered sharply, “A lot of things. An imperfect experiment. A military-industrial bully. I don’t know! Baseball, hot dogs, apple pie and . . . oh, whatever.” I was suddenly tired. “What are you even asking? It’s not one thing. You know that. Culture, counterculture. It’s a dance, an exchange. Just like anywhere.”

“And ‘American’?” she said to the group, ignoring my response. “What is the image in your mind when you think of an American? Do you picture someone like me?”

“I picture a person with a United States passport,” I said. “In case you haven’t noticed, we come in all shapes and sizes.”

“I guess you want us to say we think of a white male,” said Jan.

“The only real Americans,” she said, with the exaggerated patience of a teacher speaking to a particularly slow student, “are the Native Americans, most of whom were massacred.”

Well, no shit,

I thought, stung by her tone and the elementary political point. Was this supposed to be news?

“But when they teach us ‘American’ history in school, it’s all about white men.”

Breathe,

I told myself.

She doesn’t know you. This is your chance

to show her you’re not the enemy.

“That’s right,” I said. “It’s disgusting.”

“We were speaking about McDonald’s hamburgers,” interjected Jan. “That’s what we meant by American cul—”

“I don’t recognize any United States,” said Nadhiri, still sounding like a lecturer. “I see only Divided States. I am part of a Black nation that intends to establish its autonomy within the territory that claims that name.”

“Within the U.S.?” I asked incredulously. “How’s that gonna work?”

“We will create two or three Black-only states.”

“Which ones?” I sputtered. “And how do you plan to get the current residents to leave?”

“Why do you white liberals always get so hostile when you talk about race?”

“Me, hostile?” I was flabbergasted. “What about you? And from the word ‘go’!”

“I try to mind my own business, but you’re like a stalker, in my face, in my face . . .”

“I was trying to connect with you, but you’re so full of hate—”

“Hate? You think I hate you? I don’t care enough to hate you. I didn’t come here for you. What is it with your egos?”

“And I’m not liberal, I’m . . . progressive.” I heard how stupid it sounded as it came out of my mouth. “Radical,” I added, feebly. “I believe in radical change, from the root.”

“Radical?” she snorted. “I bet you believe in integration.”

I paused for a moment, then said uncertainly, “Yes, I do.”

“When are you love-and-peace hippies gonna figure it out? Integration doesn’t work. Shit’s worse than it ever was. At least under slavery they fed us.”

Jan and Katie had gone, though I didn’t notice them leave. I looked at Nadhiri’s face, half in shadow, half glowing pale, reflecting the pregnant moon.

I was so flustered, my tongue caught in a thick net of rage, that I could barely speak. “That kind of thinking’s just . . . Who— who can it benefit? That—it—you’re working against . . . the future, what is actually . . . It’s not a choice—races are mixing. That’s what’s true. If you like it or . . . If we don’t . . . If we don’t learn to deal with each other, it’ll all just explode in violence.”

“Get it,” she said coolly. “It’s already happening.”

The foundation for the women’s center we were building was uneven and had to be redug. A nearby baobab had spread its brawny roots farther than expected, forcing us to move the whole structure a few feet farther away. We spent the morning knocking down bricks we’d painstakingly laid the day before. Itchy with sweat and sticky red mud, we stood, panting, surveying our loss.

Facts approached us on a path through the high grass, the flesh of his heavy arms shaking as he ran. His forehead dripped; his white T-shirt was plastered to his skin. He held a folded piece of paper in his hand.

“Sistah Nadhiri,” he said. “Telegram from home.”

Facts’s round face glistened. He moved the paper away as she reached for it.

“Come,” he said. “We will read it back in camp.”

But Nadhiri grabbed the paper and scanned it. All expression dropped from her face. She stared, frozen, at the document in her hand.

“Sistah, what has happened?” asked Brown.

“Uh,” she said, a funny, pedestrian sound, as though she were clearing her throat. “Uh.” She turned and walked away from us, down the path through the yellow grass. She walked about four steps, then stopped for a long moment, stood absolutely still. Then she broke into an awkward, loping run.

“Keep working,” said Facts, going after her.

Brown threw down his shovel and followed.

The rest of us stood, looking quizzically at each other. Finally Castro, the home secretary, said, “The camp leader has said ‘keep working,’ therefore let us continue to work.” So we picked up our shovels and worked.

I heard from Katie, who heard from Jan, who heard from Facts that Nadhiri’s father was killed the night before in a random stabbing on the streets of Washington, D.C. “Stabbed in the neck,” Katie said. Facts accompanied Nadhiri to Wa and put her on a bus to Accra. Brown offered to go with her, but she said no. She left for the United States the next day. None of us heard from her again.

Castro said to me, “This bad thing happened to our sistah Nadhiri because she does not like white people. She is a racist. So, she is punished.”

Jan said, “I did not like her, but I would not wish such a thing on anyone.”

Katie said, “It’s terrible, isn’t it? Just terrible.”

Brown stared at me, but moved away when I approached.

And me? I wanted to lose myself in Brown’s smooth body, catch myself up in the touch and smell of him, where everything might make sense. But that fantasy was gone. Nadhiri stood between us—a raging, sorrowful ghost. Before she left, I’d pursued her relentlessly, though I scarcely knew why. Now I wanted to be free of her, but I couldn’t make her go.

7

Somebody’s Heart

Is Burning

Many months later, I lie on a hardwood floor in Katie’s cold London

apartment, looking at pictures of Ghana. I’m wearing one of her

sweaters, a thick Shetland wool that still smells like sheep.

“These!” Katie says. “These! Two entire rolls. I don’t get it.”

I flip through the pile, nostalgia tightening my chest. Amid hundreds

of perfect shots—faces so crisp you can see the pores, mud huts with each

blade of thatch standing out in sharp relief, silver waves caught on the

crest—twelve blurry photos. Two girls in pink dresses skid by, baskets on

their heads, a shimmer of motion. A plain cinderblock building slides

sideways out of the frame. Elongated cars, unreadable storefronts, and

more skewed women, always in motion, wrapped in bright cloth. Several

times, a dark blurred face hovers large in the corner of the frame, as though

someone had taken his own photo, holding the camera at arm’s length.

“I don’t get it,” Katie says again.

I shrug. “You left the lens cap o f?”

We look down at the photos spread across the floor.

“What town is it?” I ask.

“Wa.”

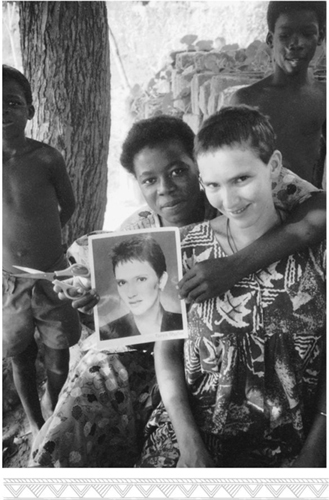

“What did we do in Wa?” I shuffle through for other Wa photos,

and find one of myself sitting with freshly cropped hair amid a gaggle of

grinning Ghanaian children. I’m holding up a ridiculous 8 x 10 glamour shot of myself, backlit and soft, taken a year before in another life—

a photo within a photo. Behind me stands a bright-eyed young woman

with a smile at once exuberant and demure.

“Christy,” I say, and Katie groans with recognition.

“Of course! Christy.” She reflects a moment, smiles, shakes her head

sadly. “Sweet Christy.”

We met Christy in Wa, capital of the Upper West Region, on a humid night after a blistering November day. Nadhiri had left the Kaleo camp, and though she wasn’t forgotten, things had settled down considerably.

Meanwhile, Katie and I had become fast friends. She was a gangly artist with a dry sense of humor and an impish grin that sparked intermittently, utterly transforming her sensible English face. On this particular day, the two of us had escaped the afternoon’s labor in Kaleo for an unapproved romp in the Big City. We’d spent the guilty hours sitting at a wooden picnic table in a shady open-air mineral bar, pressing frosty Pee Colas (the Ghanaian version of Coke) to our flushed foreheads, writing in our journals and reveling in our truancy.

We were standing on the dusty road out of Wa, waiting for transport back to Kaleo, when a girl jumped off a crowded

tro-tro

and headed straight toward us. The sun was setting, and everything was bathed in an orange glow. She was dressed in a red Western skirt and red and black striped blouse, impeccably clean and crisp. She looked like a cheerful employee in a Burger King commercial, only her smile was bigger, brighter.

“Friends!” she called. “Remember me? One week ago I showed you the post office.”

“What a coincidence,” Katie said.

In the two weeks since I’d arrived in Kaleo, Katie and I had come into Wa, the regional capital, four or five times. Each time, people approached us on the street:

Remember me? I o fered to carry

your bags when you got off the bus. Remember me? I sold you nice bread.

It had become a running gag we teased each other with, inventing new ones:

Remember me? I chased you down the block with a stick

of fried meat. Remember me? I almost ran you over with my bicycle.

“You are in Kaleo, yes?” Christy asked. “I know the white lady there. Sharon. Peace Corps. She said you would come today.”

“How could she know?” I asked lightly.

“Yes,” said Christy, cryptically. “I know so many white people. This man, Mac. VSO. He was one year in Wa here.” She reached into her bag and pulled out a photograph. It showed her, beautifully dressed in an intricate blue and gold African print, standing beside a short, scruffy young man in T-shirt, glasses, and dusty khaki pants.

“Mac,” she said proudly. “My friend. He has promised to send a letter.”

I smiled encouragingly.

“Please. I can help you,” Christy continued. “You will come to my house and greet my mother.”

“Oh, we’d love to,” said Katie, “but I’m afraid we’ve got to get back. They’re expecting us at the volunteer camp.”

“Yes,” said Christy, smiling sweetly. “There is never another lorry tonight. Tomorrow.”

“We thought we’d get a taxi,” I said, and miraculously, one appeared. Christy stepped onto the dirt road, waving her arms. The car pulled up in a cloud of dust. Peering through the window in the fading light, I saw it had no control panel, only a mass of wires. Two men shared the front seat with the driver, while two women with babies on their laps argued in the back. A young boy was sandwiched between them. Christy stepped to the window and began speaking to the driver in Wala. Soon she was shouting and gesticulating, her speech punctuated by cries of

“Eh!”

Finally she stepped back, waving her hand disdainfully at the taxi, which drove away.

“He will rob you,” she said. “Because you are white, he will charge you 3,500 cedis.”

Katie and I looked at each other. About five dollars—a fortune, in Ghanaian terms, for a half-hour cab ride.

“We do need to get back,” said Katie.

“He is a thief. My brother has a taxi. He will send you to Kaleo for 600 cedis. Come,” said Christy. She took my backpack, swung it onto her back, and reached for the camera that hung around Katie’s neck.

“Oh no, it’s okay,” said Katie, stepping back.

“Come,” Christy repeated. Laughing, she grabbed the camera strap and hoisted it over Katie’s head. She set off down the dusty road. We followed.

One thing about Africa: at night, it’s dark. In a village, if there’s no party going on, a twinkle of candlelight after 10 P.M. is a rare sight. You could walk right by a village and never know it was there. Even in a small city like Wa, which has electricity, many neighborhoods depend on kerosene lanterns, which disappear into the huts after dark.

On this occasion, the moon was a delicate sliver. As we moved outside of the central area, paved roads gave way to dirt ones, then narrowed to paths. Cinderblock houses were replaced by groupings of round mud huts. Lulled by the motion of my feet and the gentle caress of the cooling air, I followed Christy down the dirt paths, through high grass and over puddles. A gentle breeze had arisen, and the night air was pleasantly cool. I had no idea where I was going, and after a few minutes I forgot to care.

“Are we almost to your brother’s?” Katie’s voice startled me. We’d been walking a long time and seemed to be outside of town. It had been awhile since we’d seen a road, and I wondered vaguely how a taxi could get out here.

“Yes,” said Christy.

Soon we entered a compound of four or five round mud huts with thatched roofs that looked freshly trimmed, surrounded by smooth mud walls.

“Here,” said Christy proudly. “I have brought you to greet my mother.”

“I thought we were going to your brother’s,” said Katie.

“Yeah,” I chimed in, slightly alarmed.

“Yes,” Christy said. “First we chop rice. Here is my mother.”

A woman in traditional dress, with a leathery, smile-creased face, came out of the house. She was holding a baby, which she quickly passed off to Christy. She grasped our hands warmly and shouted, “You are welcome.” We responded with the word

anola

, “good evening” in the Wala language, which pleased her so much she repeated it several times, laughing loudly. I saw where Christy had gotten her brilliant smile. Four children, ranging in age from about two to twelve, hovered around the circle of light cast by her lantern, pointing at us and giggling. Katie and I looked at each other.

“You know—” I started to say, but Christy cut me off.

“We chop rice!” She gestured to a table.

I glanced at Katie again and shrugged. We sat down. Christy’s mother sat beside us. She didn’t eat, but watched closely as we consumed the rice balls and spicy groundnut soup. Whenever we slowed down, she smiled broadly and gestured for us to keep going.

“This is really trying,” Katie murmured in my ear.

“Christy,” I said, after we’d finished eating and a polite interval had passed, “we really do need to get going. People at the camp will worry about us.”

“Yes,” said Christy, smiling and making no move.

“Really,” I said.

“Really,” said Katie.

“Yes,” Christy said again. Reluctantly, she stood up, spoke to her mother in Wala.

“Thank you,” I said to her mother, also in Wala. She crowed with delight. I said to Christy, “Please tell her it was delicious.”

“Yes.”

Underway, I again lost myself in the rhythm of the walk. Lost in thought, I was only dimly aware of the neighborhoods we passed through, mostly made up of decoratively painted mud huts with glimmers of kerosene lamps coming through the windows. Occasionally we’d pass a small group of men gathered beneath a thatched overhang talking and laughing, with bottles in their hands. After about twenty minutes, Katie looked at me and raised her pale eyebrows to the hairline.

“Ah, Christy . . .” I began.

“Very soon, sistahs,” she said with such gentleness that I felt reassured.

We came to another walled compound, where a snarling dog kept Katie and me very much at bay. I’d decided against investing $300 in rabies shots before leaving the United States, and that decision haunted me now.

“It is okay,” Christy laughed. She made a calming gesture toward us, “Small, small.”

She entered the courtyard while Katie and I hovered outside, clinging to each other’s hands in solidarity. Next to the house stood a rusty vehicle.

Christy came back out. “My brother has traveled to Bolga for books. He will not return for some days.”

Katie threw me a “now what?” look, as though the whole thing were my fault.

“Christy, we’re getting really tired,” I said, suddenly feeling it. “I think we’re ready to invest in that taxi ride. Can you please direct us to the taxi park?”

“Taxi?”

“Yes, we’re willing to pay the 3,500 cedis.”

“Oh no, no, they will rob you,” she said. “Do not worry. We will visit the pastor. He will drive you.”

“Thank you,” I said firmly, “that’s very kind, but I think we’d rather pay. I’m afraid the people at the camp will be concerned about us. We weren’t even supposed to leave the camp in the first place!”

Christy stared at me.

“They’ll worry,” I repeated, with some urgency.

“No. No. Do not worry. Come.” She started off again, purposefully.

I scampered after her.

“But if the pastor’s not there,” I said, “you’ll take us back to the taxi park immediately, right?”

“Yes,” she said seriously, looking straight into my eyes.

The walk to the pastor’s house took us back to a more populated area, with cinderblock houses and dirt roads wide enough to accommodate cars. I took this as a positive sign and glanced hopefully at Katie, but she stared resolutely forward, avoiding my gaze.

The pastor’s house was dark. When Christy knocked, a woman came out of an adjoining house, calling to her. Four children of various sizes followed her and, seeing Katie and me, began calling out,

“Tubabu! Tubabu!!”—

white person in yet another tongue—all the while screaming with laughter.

“Don’t tell me,” Katie said, when Christy approached. “The pastor has traveled.”

“Yes,” said Christy, smiling sweetly.

“Now we go to the taxi park, right, Christy?” I asked.

“It is late. The taxis have gone home. You will sleep at my house.”

A band of frustration tightened around my temples. “Let’s at least look, okay? That was the deal.”

“Yes,” said Christy. “We will visit the forest manager. He has a car. He will surely send you to Kaleo.”