Somebody's Heart Is Burning (9 page)

“What a jerk!” I said.

“Eight years I was with him. Now I am twenty-seven years old. You see? He has wasted my years. I should have traveled before him. I should have been in Europe long time now.”

“What do you mean?”

“I have given him the money to go. Then, some months later, I should have followed him. My father, he had seven fishing boats. Now he has died and my stepbrothers have lost five of them with drinking. But before, I managed the affairs. I saved. I gathered 600,000 cedis, and my brother was bringing this money to Accra to arrange the visa and the plane tickets, when he was in an accident with the

tro-tro

and died. When we went to claim the body, the money was not there. Now my brother has left me with five children to provide. So I have lost my chance. I have lost my chance and my man, too.”

I looked at her in surprise, searching for something to say. I’d never imagined such a story, never sensed her underlying despair. “You’ll meet someone better,” I said, taking her hand. “Someone who values you.”

She shrugged. “I don’t want them now, these men. I see what they are. Two have betrayed me. Now the other, from before, he begs me to come back. But he has betrayed me last time, with a woman. All his friends say, ‘Santana, come back to him,’ because I used to cook for them, long time. They all love me; they remember. But I say no, he has betrayed me once, he will do it again.”

I nodded sympathetically.

“What about your man?” she asked suddenly. “Your sweet Michael.”

“What about him?”

“Why have you left him?”

“I . . . I wanted to travel . . .”

“You will go back to him?”

“Maybe. I don’t know.”

She lifted an eyebrow.

“I don’t know, Santana, I’m not sure.” I felt suddenly defensive.

“Does he beat you?”

“No,” I laughed. “No, he doesn’t beat me.”

“He goes with other women, then?”

“No. No. I mean, now, maybe, because I said we should leave things open, but when we were together, no.” The thought that he might be seeing other women now brought a painful tightness to my throat.

“So why, then? What is wrong? You think African men are more costly because you must go far to find them?”

“No! I just . . . I don’t know. I love him but . . . it’s complicated.”

“It is not complicated. He is natural resource. He needs to grow rare.”

“Stop it, Santana, I—” I stopped midsentence. How did she always manage to drive me nuts? My mind formed the words I might use to explain the situation to a friend back home:

I love

him, but I’m not sure I’m in love with him. I’m not sure he’s the one.

The words seemed unbearably childish, mere semantic diddling. I could never say them to Santana, not with that knowing smile on her face. Not in the wake of what she’d just told me.

“

Anyway,

” I continued. “We were talking about

you.

Where can we find

you

a better man?”

She shook her head. “No more man for me. My heart, it has closed.” She smiled. “Now I only torture men. I may be Ghana woman, everywhere resource, but I am more strong than they. I have no need of them, and this makes them crazy. All this they want,” she turned around slowly, swaying her hips, “but they can never have.”

“The woman is the p-property of her husband,” said Santana’s cousin Ema, short for Emanuel. He was laughing, but he was angry. I was angrier. I’d heard enough of this kind of talk during my time here to build up a reservoir of frustration. We were sitting on the weathered wooden floor around a low table, over the remains of

kenke

and pepper sauce. Santana sat beside me, silent for a change. We had all washed our fingers in a bowl of water and wiped our mouths with our wet hands. My tongue burned from the chili.

“A woman is a human being,” I said, fighting to keep my voice even. “An equal human being. Not property.”

Ema laughed again. “A woman is not equal to a m-man. See this m-muscle?”

“Physically, women and men are different,” I said. “Different strengths and different capabilities. Intellectually, they are equals.”

“But if the m-man is stronger, then the m-man must d-dominate,” Ema insisted. “That is how it is in nature.”

The topic under discussion was whether or not men had the right to beat their wives. Looking at small, slender Ema, with his gentle hands and slight stutter, it was hard to imagine him dominating anyone.

“Then does a strong man have a right to dominate a weaker man?” I asked. “Should a strong man make a weaker man his slave?”

“We are t-talking about the way things are, not the way they should be.”

“No, we’re talking about our opinions. You didn’t say, ‘Many men in Ghana treat their wives as property.’ You said, ‘The woman is the property of her husband,’ implying that you felt that was just fine.”

How we’d segued onto this topic from Christianity, I wasn’t sure. Ema had spent the entire afternoon trying to save me, a phenomenon I’d grown accustomed to during my time in Ghana. The country was brimming with fanatical Christians of every imaginable stripe. The missionaries had done their work thoroughly, and every vehicle had a religious slogan painted on the side; every business had a name like “God Is Love Beauty Saloon” (

sic

) or “Blood of Jesus Carpentry Shop.” I enjoyed flaunting my agnosticism, driving the faithful to increasingly heroic measures in their efforts to convert me. Throughout the day, I’d maintained a faintly ironic tone while Ema begged, pleaded, cajoled, and railed. Now, with the wife-beating discussion, the tables had turned. He was relaxed, content to disagree, while I was desperate to convert him to my point of view.

“History is against you,” I told him angrily. “Women are rising all over the world.”

“Ghana m-must not be part of the world, then,” he retorted.

Santana rolled her eyes. “Let the man think what he wants,” she said, pronouncing the word “man” with visible disdain.

In public, Santana treated me like a pet parrot. She’d taught me a few phrases of Fanti, most of them scatological, and as we made our daily rounds through town, she made me repeat them over and over, eliciting roars of laughter from everyone we met.

“Santana, please,” I begged her. “Stop. Just stop for a while.”

“Yes,” she would say, but within five minutes she’d demand that I do it again. “Why not make some laughter?” she asked.

“Because I’m tired of being a sideshow.”

“You are not side. You are the main show in Apam!”

My body was another point of contention. Santana was obsessed with my skinniness. During meals, I sat on the floor around a low table with the adult members of the family, each with our ball of

fufu

or

kenke

, sharing a pot of stew. Santana watched me eat as though it were the most intriguing performance she’d ever seen. If I ate slowly, she berated me to speed up. If I ate quickly, she forced another ball of

kenke

or

fufu

on me.

I’m not a large person, and in the heat, my appetite had diminished. Furthermore, in spite of years of feminist self-education, I have as much body image baggage as the next American female. Being forced to eat past the point of fullness brought up all my adolescent angst. My attempts to explain this to Santana played like a ludicrous cross-cultural Abbott and Costello:

ME: Santana, please don’t pressure me to eat more. When I eat too much, I feel bad about myself. Do you understand?

(Santana nods.)

Good. Thank you.

(I finish

my ball of

kenke,

sit back, and relax. Santana shouts something to one of the young girls, who brings another ball of

kenke

and sets it on my plate.)

ME: Santana! Didn’t you hear what I just told you? If I eat too much, I start to hate myself. I feel disgusting.

SANTANA: You hate my food!

ME: It has nothing to do with your food!

SANTANA: It shames me to have a skinny guest. We must make you fat and beautiful.

ME: (

voice rising in panic

) I don’t

want

to be fat and beautiful.

SANTANA: They will say I am starving you. That I am a bad hostess. Eat!

ME: I can’t eat another bite. I refuse to eat this

kenke.

SANTANA: (shouting) Thank you for refusing what I give you!

Meanwhile, the children hovered silently, eyeing the

kenke.

But the biggest issue was money. Santana liked to keep me guessing. Here I was, staying in her family’s home, eating their food, going everywhere with her. When I offered direct compensation, she always said no. To make up for this, I went out and bought things—large bags of rice, tins of milk, packages of sugar—and brought them to her home as gifts. Periodically, however, she spontaneously commanded me to pay for something: a

tro-tro

ride, a shopping trip, a visit to the hairdresser.

This irritated me beyond logic. I wanted consistency. The seeming arbitrariness of it made me feel off-balance, out of control. My feelings ricocheted wildly. One moment I was sure Santana was the most generous person I’d ever known. The next I had the distinct feeling she was taking advantage of me.

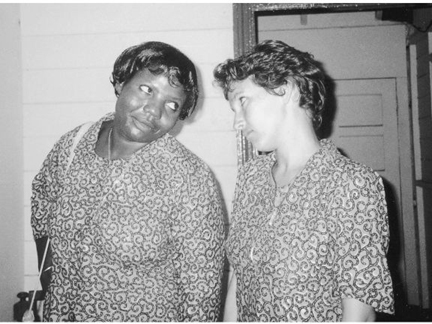

One day we dropped in on the local dressmaker. It turned out Santana had already chosen fabric and engaged the woman to make matching outfits for us. The patterns were drawn up; we had only to be measured.

The gesture moved me deeply. The fact that the material she’d selected was a neon green print with swirling yellow vines on it did nothing to dampen my enthusiasm. But when we went to pick up the finished dresses, Santana ordered me to “pay the woman.”

Again the agonizing litany: Was Santana my friend, or was she just trying to get things from me? Had she ordered the dresses as a means for us to bond, or because she wanted a new dress?

The day after the incident with the dressmaker, we shopped for the ingredients for a garden egg stew, dressed in our twin outfits. A garden egg is a popular Ghanaian vegetable that resembles a small, ovoid zucchini.

“I want to learn how to make the stew, so I can cook it for my friends back home,” I told Santana with excitement. “And I want to photograph every step of the process, to document it.”

In the cheerful chaos of the market, Santana knew everyone. She knew which woman to buy the garden eggs from, which the peppers, which the

kenke

, the palm oil, the small cube of bouillon to add flavor to the stew. We picked our way among spread-out blankets piled high with brightly colored vegetables. Women grabbed at our skirts and called out to us in passing, “Santana, buy this!

Obroni

, nice, nice.”

The shopping trip took hours. With each vendor Santana bartered endlessly, shouting, haggling, cajoling, shaking fistfuls of tiny red peppers, tomatoes, or rice in the seller’s face. Santana and the saleswomen played out a complicated drama, in which they sometimes seemed like bitter enemies, sometimes best friends. Even after an agreement had been reached, Santana would cop a coy look and ask the seller to add a few extra of whatever it was, as a bonus. The woman usually complied, a rueful expression on her face. They parted, finally, shouting half-humorous threats.