Somebody's Heart Is Burning (2 page)

In a culture where the body is usually covered, I was surprised by the women’s absolute lack of inhibition. They sat, mostly in pairs, pouring the water over their heads with small plastic pitchers, then scrubbing each other’s backs—and I mean

scrubbing.

Over and over they attacked the same spot as though trying to get out a stubborn stain, leaving reddened flesh in their wake. They sprawled across each other’s laps. They washed each other’s fronts, backs, arms, legs. Some women washed themselves as if they were masturbating, hypnotically circling the same spot. Two tiny girls, about four years old, scoured their grandmother, who lay spread-eagled on the floor, face down. A prepubescent girl lay in her mother’s lap, belly up, eyes closed, relaxed as a cat, while the mother applied a forceful up and down stroke to the length of her daughter’s torso. At the steamy heart of the baths, where the air was almost suffocating, a lone young woman reclined, back arched and head thrown back, soaping her breasts in sensual circles. With her stomach held in and her chestnut hair rippling down her back, she appeared serene and majestic—a goddess in her domain.

Abdelati’s sister, whose name was Samara, was amazed at my spiky, close-cropped hair. She called to a couple of other girls, who scooted over on their bottoms and ran their fingers through it, giggling.

“Skinny!” she exclaimed, poking at my belly.

“Il faut manger!”

She made eating gestures with her hands.

Turning me around, she went at my back with her washcloth mitt, which felt like steel wool.

“Ow!” I cried out, “Careful!”

This sent her into gales of piercing laughter, which drew the attention of the surrounding women. They joined her in appreciative giggles as she continued to sandblast my skin.

“You must wash more often,” she said, pointing to the refuse of her work—little gray scrolls of dead skin that clung to my arms like lint on a sweater.

When it came time to switch roles, I tried to return the favor, but after a few moments Samara became impatient with my wimpiness and grabbed the washcloth herself, still laughing. After polishing the front of her body, she called over a friend to wash her back. The girl scrubbed valiantly, while Samara giggled and sang.

“What was it like in there?” asked Miguel, when we met again outside. He looked pink and damp as a newborn after his visit to the men’s baths. I wondered whether his experience had been anything like mine.

“I’d like to tell you all about it,” I said eagerly, “but . . .” I paused for emphasis, then leaned in and whispered, “I don’t think Eva would approve.”

When we got back to the house, Abdelati’s mother, older sister, and uncle greeted us at the door.

“Please,” said the mother, “Abdelati is here.”

“Oh, good,” I said, and for a moment his face danced in my mind—the warm brown eyes, the smile so shy and gentle and filled with radiant life.

We entered the lovely tiled room we’d sat in before, and a handsome young Arab man in crisp Western pants and bright white button-down shirt stepped forward to shake our hands.

“Bonjour, mes amis,”

he said cautiously, his eyes darting uncertainly from my face to Miguel’s.

“Bonjour.”

I smiled, slightly confused.

“Abdelati—est-ce qu’il

est ici?”

Is Abdelati here?

“Je suis Abdelati.”

“But . . . but . . .” I looked from him to the family and then began to giggle tremulously. “I-I’m sorry. I’m afraid we’ve made a bit of a mistake. I-I’m so embarrassed.”

“Qué? Qué pasó?”

Miguel asked, urgently. “I don’t understand. Where is he?”

“We got the wrong Abdelati,” I told him, then looked around at the assembled family who’d spent the better part of a day entertaining us. “I’m afraid we don’t actually know your son.”

For a split second no one said anything, and I wondered whether I might implode right then and there and blow away like a pile of ash.

Then the uncle exclaimed heartily,

“Ce n’est pas grave!”

“That’s right,” the mother chimed in. “It doesn’t matter at all. Won’t you stay for dinner, please?”

I was so overwhelmed by their kindness that tears sprang to my eyes. For all they knew we were con artists, thieves, anything. Would such a thing ever happen back home?

Still, with my plane leaving the next morning, I felt the moments I could share with the first Abdelati and his family slipping farther and farther away.

“Thank you so much,” I said fervently, “It’s been a beautiful, beautiful day, but please . . . Could you help me find this address?”

I took out the piece of paper Abdelati had given me back in Kenitra, and the new Abdelati, his uncle, and his brother-in-law came forward to decipher it.

“This is Baâlal Abdelati!” said the second Abdelati with surprise. “We went to school together! He lives less than a kilometer from here. I will bring you to his house.”

And that is how it happened, that after taking photos and exchanging addresses and hugs and promises to write, Miguel and I left our newfound family and walked briskly through the narrow streets with this new Abdelati as our guide, until we arrived at the home of our old friend Abdelati just as the last orange streak of the sunset was fading into the indigo night. There, I threw myself into the arms of that dear and lovely young man, exclaiming, “I thought we’d never find you!”

After greetings had been offered all around, and the two Abdelatis had shared stories and laughter, we waved goodbye to our new friend Abdelati and entered a low, narrow hallway, lit by kerosene lamps.

“This is my mother,” said Abdelati.

And suddenly I found myself caught up in a crush of fabric and spice, gripped in the tight embrace of a completely veiled woman, who held me and cried over me and wouldn’t let me go, just as if I were her own daughter, and not a stranger she’d never before laid eyes on in her life.

2

Dirty Laundry

Sometimes I think I’ll never go back to the U.S. The words are

seductive, and once in a while I play them in my head, a tantalizing refrain:

never go back, never go back. Of course it’s all drama, because what do

you fill that “never” with? You still have to spend the rest of your life

somewhere.

I couldn’t escape Michael. My time in Morocco, consuming as it was, had not erased the memory of our parting. He’d held me so tightly at the airport that I could feel his heart knocking against the wall of his slender chest. He wouldn’t let go until they’d called final boarding three times. When I finally managed to pull away, he ducked his head in embarrassment, his eyes leaking tears.

I blamed myself for leaving, but I blamed him, too. In recent months, he’d started talking marriage, and talk of marriage made me extremely uncomfortable. He knew this, but he wouldn’t stop.

After countless hours of negotiations, accusations, recriminations, and apologies, we’d agreed to leave things open while I was away. We’d stay in touch, of course, but we were free to see other people, and there were no guarantees on either side about what would happen when I returned. The length of my trip was indefinite; I didn’t want to feel constrained by the idea that he was waiting for me.

I hadn’t counted on the wiliness of memory. I’d go almost an entire day without thinking of him, and then I’d turn a corner and there he’d be, his sudden, cheeky grin reflected in the face of a policeman or trinket hawker, his loose-limbed walk adorning a museum guard. His letters arrived at the Moroccan work camp every few days. Each one was quintessentially Michael: quirky, humorous, tender, filled with misspellings and the whimsical poetry of daily life. Although reading them made me homesick and confused, I felt anxious and impatient on days when they didn’t arrive. I tried to keep a tone of neutrality in the ones I sent back—to let him know that I missed him without raising false expectations. It was a difficult line to walk.

I arrived in West Africa tired and cranky. I hadn’t slept well the night before, and Abdelati’s six-year-old sister had burst into my room at five-thirty in the morning with a pot of tea. The flight itself had been an exercise in nausea control.

A con artist accosted me in front of the airport in Abidjan, the capital of Ivory Coast. He’d emerged from a small army of men who hovered outside the sliding glass doors of the baggage claim, jockeying for the attention of travelers. He was a slim African man in his early twenties, dressed in what a cynical volunteer once called “third world chic”—dark blue jeans with bright orange stitching up the sides and a carefully pressed St. Louis Cardinals T-shirt. I made the mistake of meeting his eyes. After that, there was no shaking him.

“

Bonjour, Madame.

My name is Jean-Pierre. Let me take you to your hotel. They know me; I will help you to get a better price,” he said to me in French.

“I’ve got no money for you, okay,

pas d’argent.

”

“I don’t want your money. I help you choose the hotel. If I bring you there myself, they give me commission.”

“I already know which hotel I’m going to.”

A boozy expat on the plane had looked through my guidebook and steered me away from the hotel I’d circled in Treicheville, the “African” quarter.

“Too dangerous,” he’d said. “Stay in the Central Section, or at least here, this one’s right next to the Central Section.” He poked a stubby finger at the page. “Anywhere else, they’ll sniff you out and rob you in a New York minute.” He laughed.

Although I pegged him as a racist, I decided to go with his suggestion for my first few nights. Later I would stay in the African parts of town. I hadn’t come to Africa to avoid Africans.

I got into a taxi. Jean-Pierre was next to my open window, still talking.

“Please,” he said. “This is how I live. I show tourists to the hotel, I get commission.”

“I’m not a tourist. I’m on my way to do some volunteer work in Ghana.”

“You pay nothing! The hotel, they pay.”

I sighed, and taking that as a yes, he got in. The taxi took off without setting the meter or agreeing on a price.

“Wait,” I said, “

attend

,” and Jean-Pierre, sitting beside me, repeated the phrase in a local language. How could an airport taxi driver not speak French?

“Tell him he has to set the meter,” I told Jean-Pierre. I’d read this in my guidebook:

“In Abidjan, make sure they set the meter.”

He spoke to the driver, who just kept driving. Then he turned to me.

“There is no need,” he said. “He knows the price.”

“There is a need,” my voice grew shrill, “because if he doesn’t set it, I’m getting out.”

“Small, small.” He laughed, making a calming gesture with his hand. He spoke to the driver some more. The driver barked with laughter, then slapped the meter. It came on, its electronic digits bright and reassuring. I settled back in my seat.

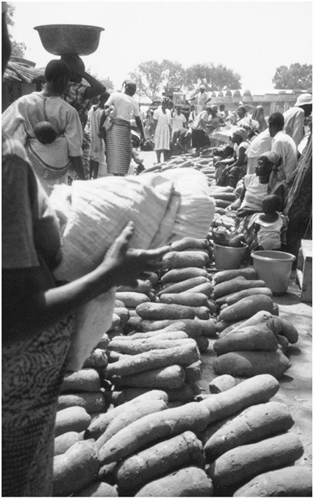

I was too tired to take in the rows of dilapidated wood and cardboard shacks and the women wrapped in bright, dissonant cloth with bundles on their heads. Too weary to crane my neck at the colorful markets with their expanse of tables piled high with everything from vegetables to virility potions to auto parts. I’d traveled enough in the “developing world” that these things seemed strangely familiar. Even the thick tropical vegetation reminded me of someplace else.

Jesus,

I thought,

what’s happened

to me? It’s my first day in sub-Saharan Africa and already I’m bored.

I did notice the peeing, though. It seemed every man in the city had sought out the most conspicuous corner he could find on which to urinate. Again and again I saw them, poised like statues in that telltale wide-legged stance, facing the wall. I leaned back in my seat.

There’s a river around central Abidjan, like a moat. As we approached the bridge to enter the downtown area, the driver suddenly swerved into a gravel parking lot.

“Ici,”

said the driver.

A hand-painted wooden sign reading

“Hôtel”

was propped against the door of an enormous stone rectangle of a building. The windows on the ground floor were boarded up.

“Are you sure this place is open?” I asked Jean-Pierre.

“Bien sûr!”

He jumped out and opened my door.

I paid the driver and he peeled off, covering me in dust.

Jean-Pierre grabbed my backpack and headed through the door.

“Improvements,” he said, gesturing at the boarded-up windows.

The stairway was narrow and dark after the bright gray outdoors. We climbed two flights and entered a deserted lobby with dirty green carpeting, a sagging sofa, and a counter that looked like a bar. At least there were windows—that stairwell made me feel claustrophobic.

A man popped up behind the counter as though he’d been crouched there, waiting. He did not seem to know Jean-Pierre. I told him I’d like a room and asked the price. Before he could answer, Jean-Pierre jumped in, speaking to him in the local language. The man answered him curtly. He turned his attention to me.

“Please, the cost is 4,000 CFA,” he said. The price, roughly thirteen dollars, was slightly more than the guidebook said. Expensive for this part of the world, but I was prepared to splurge on my first night. He reached under the bar and got a key and a form to fill out. I was ready to drop from exhaustion.

“Can I put my things in my room?” I asked. “I’ll be back in a minute.”

“Please,” the man at the desk said. Jean-Pierre accompanied me down a short, unlit hallway.

“See,” he said proudly. “I got you a good price.”

I said nothing. I dumped my things, locked the room, and headed back to the desk. I had two things on my mind: shower and laundry. I hadn’t done laundry since the volunteer project ended, and all my clothes were stuffed in my backpack in fetid lumps.

I paid the man at the desk, who introduced himself as Adjin. I thanked Jean-Pierre, and turned toward my room.

“Pardon,”

said Jean-Pierre, “you have forgotten my commission.”

“Jean-Pierre,” I said, “you told me the hotel pays the commission.”

“No! You pay the special, low price. Then you pay me commission. I got you a good price.”

I turned to Adjin.

“Did you give me a special price?” I asked.

Adjin frowned, and Jean-Pierre burst into a string of words. Adjin ignored him.

“You paid the regular price,” he told me.

“You see,” I said to Jean-Pierre, “I don’t owe you anything.”

“But I have helped you to get here!”

I handed him 300 CFA. “Goodbye,” I said.

“Uh!”

He made a high-pitched sound of disbelief.

“Jean-Pierre, I’m tired. You said you didn’t want anything from me. That is enough.”

I refused to feel guilty about the pained, vexed look in his eyes. Michael would’ve given him more money, even if he knew he was being ripped off. He was like that, generous as rain, giving of himself until there was nothing left. It was healthy to move the money through, he said, otherwise you got constipated. Consequently, I sometimes had to loan him the rent.

I went to my room, shut the door, and locked it. It was a basic room: a single bed with a mosquito net hanging above it, suspended from the ceiling by a rope and a wooden ring. A ceiling fan, a wooden chair, a tiny barred window facing a cement wall. But the bathroom held an overhead shower with running water, albeit cold. That was more than I’d had in a month. I showered, lay down on my bed, and slept.

When I emerged in the late afternoon, I asked Adjin if he knew of a place where I could do my laundry. I’d spent much of the last month on my knees in the dirt, and my light-colored cotton clothes were covered with ground-in grit. I’d scrubbed and scraped at them, but it had done nothing to lighten the dingy gray. I figured that in Abidjan, which the guidebook called the “gleaming high-rise capital” of Ivory Coast, I’d treat myself to a spin with a washing machine.