Somebody's Heart Is Burning (6 page)

4

Yao

Love, baskets of love for the baby Yao. Gardens of it. Oceans. In a village swarming with children, each of them vital and mercurial enough to

remind your heart that it can split wide open, Yao has made an impression on us all. Each day, men and women, African and foreign volunteers alike, set down our shovels for a moment, wipe the dust and sweat

from our eyes, and watch Minessi as she strolls by, tall, dark, and regal,

with Yao strapped to her back. Yao swivels his little head, working hard

to take us all in with his enormous dark eyes. And what eyes! Compassionate enough to forgive a world’s transgressions, alert enough to

awaken a planet asleep.

Forgive my gushing. I’m in love.

My first camp found me building teachers’ quarters in the village of Afranguah, in the Central Region. Unlike some of the projects I’d heard about, this one had the full support of the villagers and seemed destined to reach completion. The village women worked enthusiastically beside us, carrying buckets of water on their heads, pulling up weeds, hammering nails. Though the doors and window frames were made of wood, our primary building material was cement, which we mixed ourselves and molded into bricks, then left overnight to dry. At first it was unclear to me who was in charge—people just seemed to know what to do—but gradually a kind of hierarchy emerged. The camp leader could be seen from time to time consulting a piece of graph paper and instructing some of the experienced Ghanaian campers, who then passed on instructions to the more skilled Western volunteers. If I was assertive, some task or other would eventually trickle down to me. I soon discovered that I could just as easily sit in the shade doing nothing all morning without anyone caring or even noticing. I did my best to avoid this temptation.

On the second day, I approached a volunteer called Ballistic, who was planing some wooden boards.

“Can I try that?” I asked.

“You cannot do it,” he said, without looking up.

“I’d like to try,” said I, bristling.

At which he reiterated, “You surely cannot do it.”

I got on his case then, asking him how he’d like it if he asked me to teach him an English song, as he had the previous day, and I responded that he couldn’t learn it? After that he became my committed teacher and remained so for the next several hours, resulting in numerous uneven boards and two very sore arms.

It was the month of June, right in the middle of Ghana’s long rainy season, ostensibly the coolest time of the year. Even so, the midday sun was so excruciating for us Westerners that our workday had to be arranged around it. On an average day, we rose around five-thirty, started work by six-thirty, and broke at eleven-thirty. If it was overcast, or breezy enough to be tolerable, we’d return to work around two for a couple more hours. The rain usually hit in the late afternoon, washing away the heat and leaving the evening fragrant and cool.

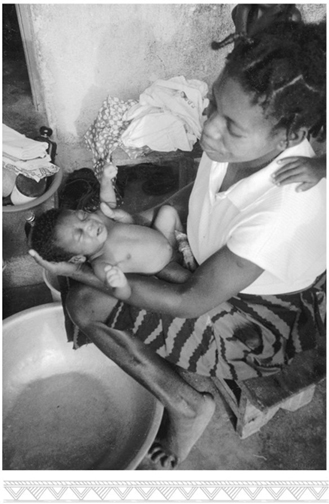

Every afternoon, as soon as we finished work, I’d tear back to the schoolhouse where we slept, grab a bucket of water and a calabash bowl, and duck behind the woven reed screens we’d set up for privacy. There, I’d shed my clothes and dump calabashes of water on myself while I soaped off the day’s grit, leaving a few inches in the bottom of my bucket for a final whoosh of cool. Then, while the other foreign volunteers hung around the camp trading travel stories, I’d scoot down to Minessi’s hut to spend some time with baby Yao before the evening meal.

Afranguah was a village of several hundred souls, with neither running water nor electricity. The inhabitants were poor, but not destitute. The children were bright and energetic, thin and scrappy, without the swollen bellies and patchy, red-tinged hair that signal malnutrition. The village had a deep borehole with a pump attached which yielded clear, sweet-tasting water, thanks to a far-reaching cooperative effort between the Ghanaian government and several international aid organizations.

An unpaved road ran through the center of town, surrounded by rectangular cinderblock houses smoothed over with stucco and topped off by corrugated tin roofs. Paths leading away from the center led to more cinderblock houses, interspersed with rectangular mud huts. My favorite of these huts had big yellow flowers growing out of its thatched roof. The surrounding countryside was lush and verdant, thick with vines and a jumble of deciduous trees. The jungle, a European volunteer told me, had been chopped down hundreds of years before and replaced by this secondary growth. The landscape was lovely, with its fecund red-brown earth, but it lacked the rain forest’s primordial complexity.

Minessi lived in one of the small stuccoed houses gathered around the center of town. She could usually be found in the communal courtyard outside her hut, washing laundry or preparing

fufu.

The women of Afranguah made

fufu

by pounding boiled cassava or yam in a large bowl, made from a scooped-out tree stump, until it acquired a smooth elasticity. While the Ghanaians loved

fufu

, most foreigners found it an acquired taste, due to the peculiar consistency. The proper way to eat it was to take a fistsized handful and swallow it down without chewing. Since doing this produced a gag reflex in the uninitiated, we novices took smaller bites, chewing it like gum until it broke apart.

The women threw their entire bodies into the pounding

.

Using heavy wooden pestles four to five feet long, they repeatedly flung their arms high above their heads and brought them down with tremendous force. Each time I watched Minessi do this, I was struck by the extraordinary grace and dignity of her movement. While most of the women in the village were short and stocky, Minessi’s figure was tall and tapered, with wide hips and a long, elegant neck. Her arms were lean, sinewy ropes. Her pounding looked like a ritual expulsion—a fierce, elegant dance.

On a typical day, Minessi would look up from her pounding as I approached. She’d smile her languid, unhurried smile and unstrap Yao from her back. Her near-black skin was smooth and lustrous; her wide-set eyes tilted slightly upward. It was obvious where Yao got his looks. The schoolteacher Amoah, an effusive, genial man whose hut was next to Minessi’s, would greet me each day with a warm cry of “Sistah Korkor, you are welcome!” Amoah’s three children would run up to me, and we’d trade exuberant greetings in Fanti. Then I’d sit on the low stool in front of Minessi’s hut, take Yao in my arms, and rock him, singing softly in his ear. He’d explain a few things to me in his own language, a kind of universal babyspeak, which resembled neither English nor Fanti so much as the call of a rapturous bird.

Minessi spoke a bit more English than the other women in Afranguah, which is to say that her vocabulary extended beyond basic greetings. Our conversations went something like this:

MINESSI: You like Yao!

ME: Yes, I do.

MINESSI: You like Yao too much!

Then she’d begin to laugh. Her laughter was like a thunder-storm, starting as a rumble, low and distant, occasionally building to a full-on roar. Soon I’d be laughing with her, and Yao too. The three of us spent a lot of time like that, laughing together for no reason at all.

“Minessi, listen,” I said one day, holding Yao’s mouth close to her ear. His breathing was raspy and labored. Minessi listened for a moment, then looked at me, confused.

I imitated the breathing, exaggerating it for effect. She gave me a long, wary look, then shrugged. I let the subject drop, but not before kissing Yao’s silky forehead and whispering in his ear that he was trying to scare me, and he should cut it out right away.

Two days later, as Minessi took her daily stroll past the construction site, she stopped and gestured to me. I set down the short pile of cement blocks I was balancing precariously on my head and skipped over. She looked at me for a moment with an anxious, indecisive expression, then whispered in my ear that she would like some money to buy medicine for Yao. Could I bring some to her house tonight?

Sure, I told her, how much did she need?

But she didn’t want to talk about it now, in front of everyone. She hurried away before I had a chance to kiss Yao.

When I arrived at Minessi’s house that afternoon, she was neither pounding nor sweeping. She was sitting on the front step, quite still, with Yao in her lap. Amoah saw me approach and called out “Sistah Korkor!” as usual. Hearing this, Minessi sprang up and dragged a stool out of her hut for me to sit on. She then disappeared again and returned with a plate of

kenke

and

shitoh. Kenke

was another Ghanaian staple, made from fermented cornmeal. It had a grainy texture, which was much more palatable to me than

fufu

’s odd plasticity, and a flavor that reminded me of sourdough bread.

Shitoh

was a sweet, dark paste, like plum sauce with a bite.

Minessi handed me the plate and gestured that I should eat, while Yao reached out his arms to me and gurgled in his throat like a dove. After I’d eaten, I swung him onto my lap. He looked up with a smile of pure delight, then stuck his fingers in my mouth and coughed. Minessi stood watching, not saying a word.

“Minessi?” I said at last. “You wanted some money for medicine?”

She glanced over at Amoah, who was playing with his children and seemed not to hear.

“Yes,” she said softly.

“How much do you need?” I asked.

Silence.

“Please tell me, Minessi. I want to help. I want to help Yao.”

“Please, you give 1,000 cedis,” she blurted.

I looked at her for a moment in astonishment, then exhaled a short sigh of relief. Less than two dollars stood between my darling and his medicine.

“That’s fine, Minessi. No problem at all.”

I reached beneath the waistband of my cotton skirt for my money belt and pulled out a small, sweaty wad. Minessi stared as I peeled off two 500-cedi notes, then watched my hands as I replaced the rest. She dropped her eyes.

“Thank you,” she said, not looking up.

A week later, our time in Afranguah was coming to an end, and Yao’s breathing was no better. It scraped and croaked. I asked Minessi whether she’d gotten the medicine, and she nodded. I told Yao to get with the program and shape up. I hugged Yao and Minessi and Amoah and Amoah’s three children. Everyone squirmed and laughed uncomfortably in my embrace. I told them I’d be back to see them after my next project.

Back in Afranguah after a month’s dusty labor in the Eastern Region, I couldn’t wait to see Yao. I wedged myself into a packed

tro-tro

for the bumpy ride from Saltpond Junction to Afranguah. In Afranguah a cadre of children greeted me with enthusiastic shouts. They accompanied me as I dumped my luggage in the cinderblock house belonging to the town minister, Billy Akwah Graham (his father met the American preacher in person once and was deeply impressed), and ran down the hill to Minessi’s mud hut with its corrugated tin roof.

Minessi was in the courtyard, pounding

fufu

with a long wooden pestle. She laughed when she saw me with my entourage and shouted, “Eh! Sistah Korkor! You are welcome!” I ran to hug her. Yao was on her back, and I covered his little head with kisses. Minessi leaned the long stick against the scooped-out wooden bowl and unwound the cloth that held Yao to her back. She handed him to me.

I looked deep into his soulful eyes and was shocked to find them glassy. Then Yao coughed: a wrenching, guttural cough that sent a shudder through his whole body. I looked up at Minessi in alarm. She started at my expression, taking a step backward.

“Yao is worse, Minessi, he’s worse.” A shrill panic came into my voice. “What happened to the medicine?” I asked.

“It is finished,” she said. “Every day, one spoon.”

She went into the hut and brought out a bottle, empty and carefully washed, with the label still on it. Examining it, I saw that it was a kind of drugstore cough syrup, cherry flavored for children.

“Oh, Minessi, who gave you this?”