Somebody's Heart Is Burning (3 page)

Adjin told me there was a woman connected with the hotel who would do the laundry for me.

“How much will it cost?” I asked him.

“Let me see the items.”

I plopped the bag on the counter.

“It’s not so much,” I said. “A skirt, a shirt, a pair of pants. . . .” I pulled the pieces out one by one. “And a bunch of little stuff.” I waved my hand toward the underwear and socks at the bottom.

Adjin looked the items over, then said, “It will cost you 500 CFA. You can collect them this evening.”

I headed downtown to change money. As I walked across the bridge, I looked down and saw a man standing on the stony riverbank, peeing into the river. I decided to leave for Ghana and my next volunteer project as soon as possible.

I walked among Abidjan’s rectangular high-rises, none of which gleamed. The air was humid as the Moroccan bathhouse, the temperature pushing a hundred degrees. Raw sewage ran down the side of the street, its odor mingling with exhaust and the faint scent of rotting vegetables. Next to the gutters, women sat stirring large metal pots of pale mush over charcoal burners or roasting skewers of gristly meat. They grabbed at my arm as I went by, scolding me in French,

“Venez, venez.”

Come.

I didn’t want to come. I didn’t want to touch their food, let alone eat it. I wanted to go home. But that was a place—and a person—to which I might never go back.

Getting service in the bank required assertiveness. Crowds of Africans and foreigners roiled around the windows with no semblance of a line. After spending half an hour in their midst with no visible progress, I began to push. As I braced my body against the human mass, a voice next to my ear croaked in melodic English, “Now you get the idea.”

I looked up at a towering Italian with curly silver hair, a Jimmy Durante nose, and a vocal cadence that made every statement a punch line. His name was Luigi, and he was vacationing in West Africa with two friends, all of them members of the Italian left, formerly the Communist party. He offered me a ride to Accra, the capital of Ghana.

“Don’t take the bus,” he said. “The buses are horrible. Filthy and crowded. Always breaking down.”

“Not very proletarian of you,” I said.

He looked startled for a moment, then bellowed with hilarity.

“When I make holiday, I become bourgeois!”

I’d thought to take public transportation and meet locals, but there’d be plenty of time for that in Ghana. I agreed to meet Luigi and his friends at their hotel the next morning.

That night the laundry wasn’t back.

“She will bring it tomorrow morning,” said Adjin.

“What time?” I asked, “because I’m meeting some friends at ten.”

“Fine, fine.”

The next morning, Adjin said, “She will bring it soon. Sit and wait. Small, small.” He laughed, making the same calming gesture with his hand that Jean-Pierre had made in the taxi. “Give me your address, and when you are back in your country, we will write to each other.”

I looked at him in surprise. We hadn’t exchanged ten words, and now he wanted to write to me?

“I’ll give it to you when I get the laundry,” I told him. I decided to meet the Italians and come back later.

“Where do you go now?” Adjin asked.

“I told you I was meeting friends at ten.” I looked at my watch. “It’s ten.”

Adjin really laughed at that one.

“You people,” he said at last, wiping his eyes, “you live by the clock.”

An hour later, I pulled up to the hotel in the back of a rented Peugeot. Luigi and his friends got a tremendous kick out of the boarded-up windows and the hand-painted “Hôtel” sign. I felt oddly slighted by their derision.

“They’re doing some repairs,” I explained huffily as I climbed out.

At the top of the stairs, Adjin greeted me with a beaming smile.

“The laundry is here,” he announced triumphantly.

“Do I get a discount for lateness? Just kidding.”

He handed me the bill. The total was 1,700 CFA.

“Hey,” I said. “This isn’t what we agreed on! You said 500.”

Adjin shrugged. “I didn’t see everything. All the slips.”

Every pair of underwear was itemized by the word “slip.”

“Well, I showed you what was here. This is more than three times what you said it would be.”

He shrugged again.

“This is what the woman charges.”

This wasn’t right. I had to resist this stuff. Not give in to guilt. Otherwise I’d be taken for a ride every step of the way. I’d seen it happen often enough.

“I’m going to pay what we agreed on,” I said. “Five hundred CFA.”

“But the price, it is not up to me,” said Adjin. “It is the woman who does the laundry. If you don’t give it to me, I must pay her from my own pocket.”

“You should have thought of that when you quoted me a price. I can’t afford this.” I slapped the bill. “If I’d known it would be this much I would have washed it myself.”

“Oh!” he said, with some surprise.

“I’m not rich, you know. I’m not a tourist. I’m a volunteer.”

“Why don’t you stay and speak to her yourself. She will come soon.”

“I can’t stay,” I said, exasperated. “My friends are waiting for me in the car.” I paid him the 500 CFA and turned to go. The laundry, folded and wrapped in brown paper, was heavy in my hands.

“It’s a little damp,” he said. Then he called after me, “You forget.”

I turned around. He had a big smile on his face.

“You have forgotten to leave me your address.”

I didn’t understand this guy at all. Sighing, I went to the bar and wrote out my address.

“Are you sure you will not speak to her?” he asked as I left.

I set the laundry beside me on the back seat as we drove away from the hotel. I refused to feel guilty. 1,700 CFA was over five dollars—not a lot at home, but a small fortune here. I didn’t want to be a dumb tourist, conned and conned again. If I was going to draw this trip out as long as I hoped to, every dollar counted.

“What is the matter, comrade?” Luigi asked jovially. “The cat has captured your tongue?”

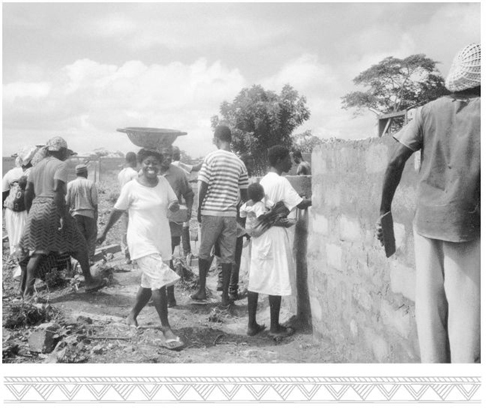

As we pulled out of town we passed a broad hillside, completely covered in laundry. Shirts, pants, dresses, and bedsheets were spread across the high grasses as far as the eye could see. In the river below, women knelt on flat rocks, wringing and scrubbing, their bodies swaying back and forth. Suds drifted lazily downstream in the brown water.

Ivory Coast is one of the wealthier countries in West Africa, and the roads are very well kept. Our Peugeot wound its way over smooth black tarmac amid a spectacular tropical tangle: festooning vines, palms with wide, flat leaves, gangly saplings with frizzy heads. Men and women tromped along the sides of the road, carrying bundles of sticks and baskets of bananas on their heads. In the midafternoon we stopped at a restaurant, ducking beneath the thatched overhang just as the rain hit. For a moment I thought of Michael, how he loved that time of day, the way the greens and yellows popped out in the dying light. I drank orange Fanta from a rusty-necked bottle and munched popcorn as the boys played checkers. And for a moment, I touched something . . . happiness?

Why here? Why now?

Why did I run halfway across the globe if this was all it took—just to sit, in the company of others, with rain, laughter, mild air, fragrant earth?

Late that night, deep in the rain forest between Abidjan and Accra, in a room furnished exactly like the one I’d slept in the night before, I unwrapped the brown paper packages. My light-colored clothes gleamed in the dark room. They were spotless. Every trace of Moroccan grime, dust that I’d thought permanently ground in, was gone. Someone must have spent hours, to succeed so thoroughly where I had repeatedly failed. Each item, every shirt and sock and pair of underwear, lay neatly pressed against the brown paper, brighter and more beautiful than when it was new.

3

The Girl

Who Drank Petrol

When I think of Hannah, I always see her in the same spot. She’s near

downtown Accra, striding along a red dirt path above the beach. Flecks

of ash dance in the air. Beside the path a woman sits on a low stump,

roasting plantains on an iron grill, while far below the raggedy silver

ocean laps at the pale sand. Hannah walks fast, feet turned out, cheeks

pink with exertion, curly golden hair bouncing, chest and chin up, bright

green eyes fixed straight ahead. She is purposeful and oblivious, at home

in her city, her Ghana, her world.

The first time I saw the Dutch volunteer called Hannah, she was sitting on the sun-bleached wooden steps of the volunteer hostel at high noon, surrounded by African men. I’d arrived in Ghana from Ivory Coast the night before and was making my first tentative sojourn into the achingly bright day. The assembled men shouted boisterously, cheerfully one-upping each other, vying for Hannah’s attention. She reclined against the top step, all pink cheeks and yellow curls, flirting and sassing like some kind of postmodern Scarlett O’Hara. I was just about to scoot past her onto the footpath into town, when she turned to me abruptly and said, “Did you know I almost died?”

“Really?” I asked uncertainly.

“Yes!” she said brightly. “Only two weeks ago! I had malaria, but it was the kind where you are not aware that you have it, and you become more and more . . . how do you say . . . like a slow and creeping worm? You walk like this,” she stuck out her arms like a zombie, “and laugh all the time like this,” she demonstrated a vague, high-pitched giggle, “and you have no desire to eat anything. I ate no food for five days. Then when I went to the hospital, the doctor said if I had waited one day longer I would have died.” Her accent was soft and rounded, difficult to place.

“Our sistah was looking sooooo skinny!” one of the African men chimed in. “We make her chop

fufu

six times a day now, so she will be plump and beautiful again.” He poked her in the side.

“Chop

fufu

?” I said.

“Chop,” said Hannah, gesturing toward her mouth and chomping her jaw up and down. “

Fufu

is Ghana food—you must try some very soon.” The man poked her again and she giggled, “Stop it, Gorby!”

“Gorby?” Everything felt bewildering in the hard, flat light.

“My camp name,” he said, extending a strong, slender hand. “Claude Mensah, a.k.a. Mensah Mensah Gorbachev, at your service.” He grinned at me with such genuine warmth that I giggled in response.

“But we just call him Gorby,” said Hannah. “Don’t we?” She rubbed her hand across his close-cropped hair. “And he is my dear, dear friend. Gorbachev is his camp name. And this is Ninja, Momentum, Ayatollah, and Castro.” I shook hands all around, dizzied by the wattage of smiles. “At camp, the Africans take foreign names and the foreigners take African names. Have you been to camp yet?”

I shook my head. “I just got here last night.”

The work projects, which took place in the rural areas, were called camps. Foreign volunteers paid $200 for a year’s membership and then participated in as few or as many camps as they chose during that time. At camp, the volunteers were given room and board. When not at camp, they were welcome to stay here, in the Accra hostel, for as long as they liked. The hostel was a low-ceilinged wooden building, painted olive drab like a military barracks, which housed both a volunteer dormitory and the organization’s offices. The dormitory was a long, low-ceilinged room, which fit about thirty bunk beds. Each upper bunk had a hook above it on which the volunteer could hang a mosquito net. Those on the lower bunks attached their nets to the metal lattice of the bed above. The overhead fan worked sporadically, and the rough wooden floor bestowed many splinters on tender pink soles. Sunlight filtered in through small, screened windows. In midsummer, when the hostel was packed with volunteers, the bunks were supplemented by mattresses on the floor.

The hostel was for foreigners only. Ghanaian volunteers were expected to live at home when not participating in camps, although they were welcome to visit during the day. Ghanaians who complied with certain criteria could participate in the camps free of charge. No one seemed to know exactly what those criteria were, but all the Ghanaian volunteers were literate, spoke good English, and had families that were financially able to spare them. With a few exceptions, they were city youth, getting a taste of the countryside. Some of them seemed as alien to the lives and customs of the villagers as we foreigners were.

A few local young men who were not volunteers hung around the hostel during the day, practicing their English and hoping to develop friendships with foreigners that would lead to marriage, employment, or at the very least sponsorship for a journey abroad. These men were clean-cut and solicitous, and many of the foreign women were all too eager to take advantage of the opportunity for roadside romance (and if that’s all it turned out to be, the men didn’t seem to mind too much either). As a brunette, I didn’t get quite the attention the blondes did, but I got enough. Too much, even. I was still far too confused about the relationship I’d left behind to think about flirting. Michael’s and my letters had slipped back into a tone of such intimacy it was as if we were still together. On my stronger days, this felt like a burden—I worried that my homesick heart was writing checks my itinerant body wouldn’t keep. But on days when I felt most unrooted, it was a tremendous comfort to know that he was there.

Periodically throughout the day, Mr. Awitor, the head of the organization, emerged from an inner office to chase away nonvolunteers with harsh words in one of the local languages. He often added in English—presumably for our benefit— “If I see your face here again, I will surely telephone the police.”

“We don’t mind them,” the foreign volunteers insisted, but he simply shook his head and walked back inside, murmuring under his breath that we would surely mind when our costly cameras and sunglasses went missing. The young men always reappeared an hour or two later anyway. Though Mr. Awitor’s tone was menacing, they’d learned by now that the threatened phone call was never made.

Some foreigners participated in one camp and simply stayed on at the hostel for the rest of the year, bumming around Accra and smoking potent local marijuana, called “bingo” or “wee.” Hannah, however, had been in Ghana for three months and already participated in four camps.

“We must choose your name!” Hannah clapped her hands with delight. “What shall we call her, Gorby?”

“We must call her Korkor,” he said, “like my baby sistah.”

“Korkor,” I said. It sounded like kaw-KAW. “What does it mean?”

“It means second-born, in Ga,” said Gorby.

“Are you second-born?” asked Hannah.

“To my mother I am.” I was about to explain that my father had older children from a previous marriage, but Hannah interrupted.

“Perfect! Gorby is . . . how do you call it . . . Soo-kick?”

“Psychic,” I said.

“Psychic! Gorby is psychic!”

“What’s your camp name?” I asked Hannah.

“Mine is Abena,” she said, “Tuesday-born in Fanti. Everyone here has a day name. But then there are also nicknames and family names and Christian names. Africans have so many names, it is very confusing.”

“Not to us,” said the man called Momentum.

“Only to girls from Holland,” added Gorbachev. He flashed her an adoring grin.

Later Hannah confided in me that back home in Amstelveen, the suburb of Amsterdam where she grew up, she’d never considered herself attractive. She had not been popular in school, she told me. She was always isolated. Boys picked on her, girls whispered about her, and she had few friends.

“But you’re so beautiful!” I stammered. “Not to mention smart, and sweet, and vivacious. You would’ve been very popular at my high school, I can promise you that.”

She looked at me warily. “I don’t think I should thank you for telling me lies. I may be smart, but I am not beautiful.”

“You’re—”

“Stop it,” she said sharply, and something in her tone prevented further protest. “I know what I am. Anyway, it is all past. I am not in Holland now. I am in Ghana, and here I will be a new Hannah, a completely new girl.”

I never found out what the old Hannah was like, but this new girl was a charmer. She insinuated herself into my brittle heart the way a child might, and in fact she was like a child, begging for attention, pouting when she didn’t get it, pointing out her own best attributes at full volume, basking in the world’s love. Among the volunteers, she was the favorite daughter of Africans and foreigners alike, doted on and pampered. She was a baby, really, not even twenty, and though there were others around that age (I was practically the grandmother of the group at twenty-six going on twenty-seven), there was something about her that made you want to protect her, to take care.

Hannah had a flair for drama. Once she leaned over in the night to take a swig from her water bottle and got a big swallow of gasoline instead. She ran to the bathroom and spent the rest of the night vomiting. The burning sensation lingered in her throat throughout the following day.

“I drank petrol!” she crowed to the group on the steps the next day. “You must tell your children and grandchildren this story, so that the girl who drank petrol will become a legend. You must tell them that after that day this girl had the power to light a fire with only her breath.”

In Accra I was initially put off, as I had been in Abidjan, by the gaping holes in the sidewalk, the open sewers running down the sides of the streets, and the curbside food stands swarming with flies. The fumes of gasoline, human waste, and charred meat nauseated me. I was beleaguered as well by boisterous strangers who accosted me on the street, shouting, “What is your name? Let me be your friend! Give me your address! Bring me to your country!” I wondered sourly whether these overtures constituted the legendary Ghanaian friendliness.

But within two weeks I no longer noticed the sewage or the flies, and I was gobbling up street food like it was going out of style. I relished it all—the dark green

kontumbre

with its texture of creamed spinach; the thick, savory groundnut stew (Ghanaian for peanut) with sticky rice balls; salty

Jollof

rice flavored with bits of egg and fish; tart, juicy pineapple; sweet oranges stripped of their peels but still clothed in their white felt under-skins; starchy cocoyams;

kenke

;

banku

;

shitoh

;

akieke . . .

All the stews were heavy with palm oil, its drowsy flavor reminiscent of coconuts and cashews. But far and away my favorite street food was

keli-weli

, a spicy-sweet concoction made of small chunks of plantain fried to a crisp in palm oil, then sprinkled amply with ginger and chili pepper for a sharp, tangy bite.

Simply put, I loved Accra. While embracing the amenities of running water and electricity, it maintained a character all its own. No New York–style high-rises to be found here. Instead it unfolded, neighborhood by colorful neighborhood, a curious mixture of African and European influence, opening outward from the center like an elaborate tropical bloom. Accra was alive. Every city block pulsated with energy, from the solid cement buildings of the downtown area to the tin-roofed shacks of the poorer neighborhoods, from the sweltering maelstrom of the Makola Market to the crumbling castle that housed the government offices. In any one of these places, you were as likely to see a man dressed head to toe in full African regalia as you were to see a woman in jeans, tube top, and high-heeled shoes. And the colors! Brilliant shades of orange and red, turquoise and lilac, fuchsia and teal. The African fabrics would make a flamingo look drab. The prohibitions against combining reds and pinks or circles and stripes were absent here. Fabrics of every description lived side by side in delirious dissonance, a dizzying visual feast. The hairstyles too were astonishing. Some adorned the women’s heads like helmets, with sharp spikes sticking out in every direction. Others were elaborate multi-tiered sculptures, their interlacing layers balanced against each other like houses of cards. Still others were interwoven with beads and ribbons, which complemented the colorful outfits with extra splashes of light.