The 30 Day MBA (17 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

TABLE 2.3

Â

Using discounted cash flow (DCF)

$/£/⬠| Discount factor | Discounted | |

Cash flow | at 15% | cash flow | |

A | B | A Ã B | |

Initial cash cost NOW (Year 0) | 20,000 | 1.00 | 20,000 |

Net cash flows | |||

Year 1 | 1,000 | 0.8695 | 870 |

Year 2 | 4,000 | 0.7561 | 3,024 |

Year 3 | 8,000 | 0.6575 | 5,260 |

Year 4 | 7,000 | 0.5717 | 4,002 |

Year 5 | 5,000 | 0.4972 | 2,486 |

Total | 25,000 | 15,642 | |

Cash surplus | 5,000 | Net present value | (4,358) |

The formula for calculating what a pound received at some future date is:

Present Value (PV)

=

$/â¬/£P

Ã

1/(1

+

r)

n

where $/£/â¬P is the initial cash cost, r is the interest rate expressed in decimals and n is the year in which the cash will arrive. So if we decide on a discount rate of 15 per cent, the present value of a pound received in one year's time is:

Present Value

=

$/â¬/£1

Ã

1/(1

+

0.15)

1

=

0.87 (rounded to two decimal places)

So we can see that our $/£/â¬1,000 arriving at the end of year 1 has a present value of $/£/â¬870; the $/£/â¬4,000 in year 2 has a present value of $/£/â¬3,024 and by year 5 present value reduces cash flows to barely half their original figure. In fact, far from having a real payback in year 4 and generating a cash surplus of $/£/â¬5,000, this project will make us $/£/â¬4,358 worse off than we had hoped to be if we required to make a return of 15 per cent. The project, in other words, fails to meet our criteria using DCF but might well have been pursued using payback.

Internal rate of return (IRR)

DCF is a useful starting point but does not give us any definitive information. For example, all we know about the above project is that it doesn't make a return of 15 per cent. In order to know the actual rate of return we need to choose a discount rate that produces a net present value of the entire cash flow of zero, known as the internal rate of return. The maths is complex but Microsoft has a neat template (

http://office.microsoft.com/engb/templates/internal-rate-of-return-irr-calculator-TC001234202.aspx

) that will crunch the numbers for you. They also have a whole host of other templates that you can reach by typing their name â payback period, present value, discounted cash flow and so forth.

Using this spreadsheet you will see that the IRR for the project in question is slightly under 7 per cent, not much better than bank interest and certainly insufficient to warrant taking any risks for.

Budgeting is the principal interface between the operating business units and the finance department. As a staff function (see

Chapter 4

for more on line and staff functions), the finance department will assist managers in preparing a detailed budget for the year ahead for every area of the organization and is in effect the first year of the business plan. MBAs are invariably expected to play a role in facilitating the process within their departments. Budgets are usually reviewed at least halfway through the year and often quarterly. At that review a further quarter or half year can be added to the budget to maintain a one-year budget horizon. This is known as a ârolling quarterly (half yearly) budget'.

Budget guidelines

Budgets should adhere to the following general principles:

- The budget must be based on realistic but challenging goals. Those goals are arrived at by both a top-down âaspiration' of senior management and a bottom-up forecast of what the department concerned sees as possible.

- The budget should be prepared by those responsible for delivering the results â the salespeople should prepare the sales budget and the production people the production budget. Senior managers must maintain the communication process so that everyone knows what other parties are planning for.

- Agreement to the budget should be explicit. During the budgeting process, several versions of a particular budget should be discussed. For example, the boss may want a sales figure of $/£/â¬2 million, but the sales team's initial forecast is for $/£/â¬1.75 million.

- After some debate, $/£/â¬1.9 million may be the figure agreed upon. Once a figure is agreed, a virtual contract exists that declares a commitment from employees to achieve the target and commitments from the employer to be satisfied with the target and to supply resources in order to achieve it. It makes sense for this contract to be in writing.

- The budget needs to be finalized at least a month before the start of the year and not weeks or months into the year.

- The budget should undergo fundamental reviews periodically throughout the year to make sure all the basic assumptions that underpin it still hold good.

- Accurate information to review performance against budgets should be available 7 to 10 working days before the month's end.

Variance analysis

Explaining variances is also an MBA-type task so performance needs to be carefully monitored and compared against the budget as the year proceeds, and corrective action must be taken where necessary. This has to be done on a monthly basis (or using shorter time intervals if required), showing both the company's performance during the month in question and throughout the year so far.

Looking at

Table 2.4

, we can see at a glance that the business is behind on sales for this month, but ahead on the yearly target. The convention is to put all unfavourable variations in brackets. Hence, a higher-than-budgeted sales figure does not have brackets, while a higher materials cost does. We can also see that, while profit is running ahead of budget, the profit margin is slightly behind (â0.30 per cent).

TABLE 2.4

Â

The fixed budget ($/£/â¬

000

's)

Heading | Month | Year to date | ||||

Budget | Actual | Variance | Budget | Actual | Variance | |

Sales | 805 | 753 | (52) | 6,358 | 7,314 | 956 |

Materials | 627 | 567 | 60 | 4,942 | 5,704 | (762) |

Materials margin | 178 | 186 | 8 | 1,416 | 1,610 | 194 |

Direct costs | 74 | 79 | (5) | 595 | 689 | (94) |

Gross profit | 104 | 107 | 3 | 820 | 921 | 101 |

Percentage | 12.92 | 14.21 | 1.29 | 12.90 | 12.60 | (0.30) |

This is partly because other direct costs, such as labour and distribution in this example, are running well ahead of budget.

Flexing the budget

A budget is based on a particular set of sales goals, few of which are likely to be exactly met in practice.

Table 2.4

shows a company that has used $/£/â¬762,000 more materials than budgeted. As more has been sold, this is hardly surprising. The way to manage this situation is to flex the budget to

show what, given the sales that actually occurred, would be expected to happen to expenses. Applying the budget ratios to the actual data does this. For example, materials were planned to be 22.11 per cent of sales in the budget. By applying that to the actual month's sales, a materials cost of $/£/â¬587,000 is arrived at.

Looking at the flexed budget in

Table 2.5

, we can see that the company has spent $/£/â¬19,000 more than expected on the material given the level of sales actually achieved, rather than the $/£/â¬762,000 overspend shown in the fixed budget.

TABLE 2.5

Â

The flexed budget (

$

/

£

/â¬

000

's)

Heading | Month | Year to date | ||||

Budget | Actual | Variance | Budget | Actual | Variance | |

Sales | 753 | 753 | â | 7,314 | 7,314 | â |

Materials | 587 | 567 | 20 | 5,685 | 5,704 | (19) |

Materials margin | 166 | 186 | 20 | 1,629 | 1,610 | (19) |

Direct costs | 69 | 79 | (10) | 685 | 689 | (4) |

Gross profit | 97 | 107 | 10 | 944 | 921 | (23) |

Percentage | 12.92 | 14.21 | 1.29 | 12.90 | 12.60 | (0.30) |

The same principle holds for other direct costs, which appear to be running $/£/â¬94,000 over budget for the year. When we take into account the extra sales shown in the flexed budget, we can see that the company has actually spent $/£/â¬4,000 over budget on direct costs. While this is serious, it is not as serious as the fixed budget suggests.

The flexed budget allows you to concentrate your efforts on dealing with true variances in performance.

The following website, SCORE (

www.score.org/resources/sales-forecast-1

), has a downloadable Excel spreadsheet from which you can make sales and cost projections on a trial and error basis. Once you are satisfied with your projection, use the profit and loss projection (

www.score.org/resources/3-year-profit-and-loss-projection

) to complete your budget.

Seasonality and trends

The figures shown for each period of the budget are not the same. For example, a sales budget of $/£/â¬1.2 million for the year does not translate to $/£/â¬100,000 a month. The exact figure depends on two factors:

- The projected trend may forecast that, while sales at the start of the year are $/£/â¬80,000 a month, they will change to $/£/â¬120,000 a month by the end of the year. The average would be $/£/â¬100,000.

- By virtue of seasonal factors, each month may also be adjusted up or down from the underlying trend. You could expect the sales of heating oil, for example, to peak in the autumn and tail off in the late spring.

See also

Chapter 11

, Quantitative and qualitative research and analysis, for more on forecasting.

- Measuring markets

- Assessing strengths and weaknesses

- Understanding customers

- Segmenting markets

- The marketing mix

- Selling

- Researching markets

B

usiness schools didn't invent marketing but they certainly ensured its pre-eminence as an academic discipline.

Principles of Marketing

and

Marketing Management

, seminal books on the subject by Philip Kotler (

et al

) of Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, have been core reading on management programmes the world over for decades. The School's marketing department has rated at the top in all national and international ranking surveys conducted during the past 15 years. (You can see Kotler lecture at this link:

www.anaheim.edu/Resources

> CEO Video Interviews).

Marketing is defined as the process that ensures the right products and services get to the right markets at the right time and at the right price. The devil in that sentence lies in the use of the word âright'. The deal has to work for the customer, because if they don't want what you have to offer the game is over before you begin. You have to offer value and satisfaction, otherwise people will either choose an apparently superior competitor or, if they do buy from you and are dissatisfied, they won't buy again. Worse still, they may bad-mouth you to a lot of other people. For you the marketer, being right means that there have to be enough people wanting your product or service to make the venture profitable; and ideally those numbers should be getting bigger rather than smaller.

So inevitably marketing is something of a voyage of discovery for both supplier and consumer, from which both parties learn something and

hopefully improve. The boundaries of marketing stretch from inside the mind of the customer, perhaps uncovering emotions they were themselves barely aware of, out to the logistic support systems that get the product or service into customers' hands. Each part of the value chain from company to consumer has the potential to add value or kill the deal. For example, at the heart of the Amazon business proposition are a superlatively efficient warehousing and delivery system and a simple zero-cost way for customers to return products they don't want and get immediate refunds. These factors are every bit as important as elements of Amazon's marketing strategy as are its product range, website structure, Google placement or its competitive pricing.

Marketing is also a circuitous activity. As you explore the topics below, you will see that you need the answers to some questions before you can move on, and indeed once you have some answers you may have to go back a step to review an earlier stage. For example, your opinion as to the size of the relevant market may be influenced by the results achieved when you segment the market and assess your competitive position.

Getting the measure of markets

The starting point in marketing is definition of the scope of the market you are in or are aiming for. This comes from the business objectives, mission and vision that form the heart of the strategy of the enterprise. These are topics covered in

Chapter 12

on strategy. For most MBAs for most of the time these will be a âgiven' and as such will not inhibit your ability to apply the marketing concepts explored in this chapter. So, for example, if you are working in, say, Body Shop, McDonald's, IBM, a Hospital Trust or the Prison Service, the broad market thrust of your current business will be self-evident. Later you may want or need to change strategic direction, but effective marketing is concerned fundamentally with dealing with a defined product (service)/market scope. These concepts apply to any marketing activity, but you will find that understanding them is made easier by applying them to the business you are in, or have some appreciation of.

Assessing the relevant market

Much of marketing is concerned with achieving goals such as selling a specific quantity of a product or service or capturing market share. MBAs are frequently set the challenging task of measuring the size of the market. Now in principle this is not too difficult. Desk research (see in âMarket research' later in this chapter) will yield a sizeable harvest of statistics of varying degrees of reliability. You will be able to discover that the consumption, say, of bread in Europe is £10 ($16/â¬11) billion a year. But first you need a definition of bread. The industry-wide definition of Bakery includes sliced

and un-sliced bread, rolls, bakery snacks and speciality breads. It covers plant-baked products; those that are baked by in-store bakers; and products sold through craft bakers.

Assessing the relevant market then involves refining global statistics down to provide the real scope of your market. If your business operates only in the UK the market is worth over £2.7 ($4.2/â¬3.03) billion, equivalent to 12 million loaves a day, one of the largest sectors in Food. If you are operating only in the craft bakery segment then the relevant market shrinks to £13.5 ($21.16/â¬15.16) million; this contracts still further to £9.7 ($15.2/â¬10.9) million if you are, say, operating only within the radius of the M25 ring road.

CASE STUDY

Â

Google fits in

Google China, founded in 2005, was headed by former Microsoft executive, Kai-Fu Lee, until 4 September 2009. The Chinese government operated, and still does, a level of censorship on all communication media, alien to Western culture. To enter the Chinese market Google had to operate a form of uncomfortable self-imposed censorship known as the âGolden Shield Project'. The effect of this was that whenever people in China searched for keywords on a list of blocked words maintained by the government, google.cn displayed the following at the bottom of the page (translated): âIn accordance with local laws, regulations and policies, part of the search result is not shown.'

By the start of 2010 Google had only a third of the search-engine market in China, where the market was dominated by local giant Baidu. Though its sales revenues continued to rise, it was finding business hard going. On 12 January 2010, Google and more than a score of other US companies recognized that they had been under cyber attack from organizations based in mainland China. On 12 January 2010 Google declared it was no longer willing to censor content on its Chinese site after discovering that hackers had obtained proprietary information and e-mail data of some human-rights activists. On 22 March, Google decided to stop censoring Chinese internet searches and shifted its search operations from the mainland to an unfiltered Hong Kong site, in effect reversing its original decision to comply with local conditions. There is little evidence that this marketing strategy has been effective since Google Inc's share of China's online-search market had, by 2012, declined to barely 15 per cent. Baidu, the market leader's share, was 78 per cent and Sogou Inc held just short of 3 per cent.

The importance of market share

The relevant market will be shared by various competing businesses in different proportions. Typically there will be a market leader, a couple of market followers and a host of businesses trailing in their wake. The slice that each competitor has of a market is its market share. You will find that marketing people are fixated on market share, perhaps even more so than on absolute sales. That may appear little more than a rational desire to beat the âenemy' and appear higher in rankings, but it has a much more deep-seated and profound logic.

Back in the 1960s a firm of US management consultants observed a consistent relationship between the cost of producing an item (or delivering a service) and the total quantity produced over the life of the product concerned. They noticed that total unit costs (labour and materials) fell by between 20 and 30 per cent for every doubling of the cumulative quantity produced. (See

Chapter 12

for more on the experience curve effect.)

So any company capturing a sizeable market share will have an implied cost advantage over any competitor with a smaller market share. That cost advantage can then be used to make more profit, lower prices and compete for an even greater share of the market, or invest in making the product better and so stealing a march on competitors.

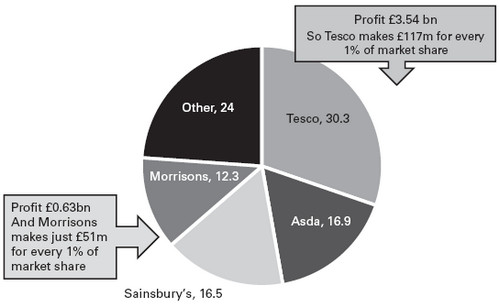

Figure 3.1

demonstrates clearly the advantage of market share in the supermarket business. Tesco, the market leader, made over twice as much profit per percentage point of market share as Morrisons.

FIGURE

3.1

Â

Market share UK supermarkets

2011â12

Competitive position

It follows that if market share and relative size are important marketing goals, you need to assess your products' and services' positions relative to the competition in your relevant market. The techniques most used to carry out this analysis are SWOT and perceptual mapping.

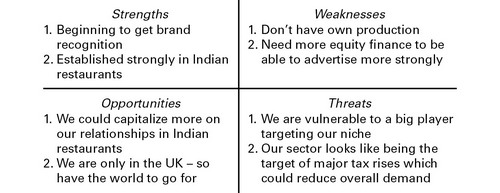

Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT)

This is a general-purpose tool developed in the late 1960s at Harvard by Learned, Christensen, Andrews and Guth, and published in their seminal book,

Business Policy, Text and Cases

(Richard D Irwin, 1969). The SWOT framework consists of a cross, with space in each quadrant to summarize your observations, as in

Figure 3.2

.

FIGURE

3.2

Â

Example SWOT chart for a hypothetical Cobra Beer competitor

In this example the SWOT analysis is restricted to a handful of areas, though in practice the list might run to a dozen or more areas within each of the four quadrants. The purpose of the SWOT analysis is to suggest possible ways to improve the competitive position and hence market share while minimizing the dangers of perceived threats. A strategy that this SWOT would suggest as being worth pursuing could be to launch a low-alcohol product (and sidestep the tax threat) that would appeal to all restaurants, rather than just Indian (widen the market). The company could also start selling in India using the international cachet of being a UK brand. That would open up the market still further and limit the damage that larger UK competitors could inflict.

SWOT is also used as a tool in strategic analysis and indeed it was so used by General Electric in the 1980s. While it is a useful way of pulling together a large amount of information in a way that is easy for managers to assimilate, it can be most effective when used in individual market segments, as a strength in one segment could be a weakness in another. For example, giving a product features that would enhance its appeal, say, to the retirees market may reduce its appeal to other market segments.

Perceptual mapping

Perceptual or positioning maps are much used by marketing executives to position products and services relative to competitors on two dimensions. In

Figure 3.3

the positions of companies competing in a particular industry are compared on price and quality, on a spectrum from low to high.

FIGURE

3.3

Â

Perceptual mapping