The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (16 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

The Pastorius saboteurs were:

- Ernest Peter Burger, who had worked as a machinist in Detroit and Milwaukee and been a member of the Michigan National Guard

- George John Dasch, alias George Davis, alias George Day, who at age thirty-nine was the oldest of the group, had been a waiter in New York, and had served in the U.S. Army Air Corps

- Herbert Hans Haupt, who had worked for an optical firm in Chicago and at twenty-two was the youngest of the saboteurs

- Heinrich Heinck, alias Henry Kanor, who had been employed as a waiter in New York City

- Edward Kerling, alias Edward Kelly, who had been with a New Jersey oil corporation and had been a butler

- Hermann Neubauer, alias Herman Nicholas, who had been a cook in Chicago and Hartford hotels

- Richard Quirin, alias Robert Quintas, who had worked in the United States as a mechanic

- Werner Thiel, alias John Thomas, who had been employed in Detroit automobile plants

Masterminding the elaborate sabotage scheme had been pudgy, bullnecked Lieutenant Walter Kappe, who had beat the propaganda drums for Nazi-front groups in New York City and Chicago in the 1930s. Returning to Germany in 1937, he had been given a commission in the Abwehr, the Third Reich’s cloak-and-dagger agency.

Kappe had recruited the eight saboteurs and put them through a rigorous routine of secret writing, incendiaries, explosives, fuses, timing devices, grenade-pitching, and rifle shooting. Each man had to memorize scores of targets in the United States. They rehearsed phony life stories over and over, backgrounds that were documented with bogus birth certificates.

They Came to Blow Up America

77

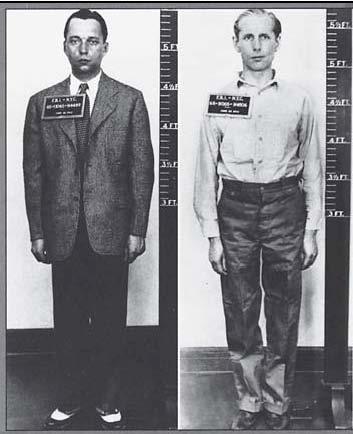

Operation Pastorius ringleaders were Ernest Burger (left), a former member of the Michigan National Guard, and George Dasch, who had served in the U.S. Army Air Corps. (FBI)

On May 23, 1942, the saboteurs were divided into two teams and given their boom-and-bang assignments in the United States.

Team No. 1 would be led by the “old man,” George Dasch, and include Burger, Heinck, and Quirin. It was to destroy hydroelectric plants at Niagara Falls, New York; blow up Aluminum Company of America factories in East St. Louis, Illinois; Alcoa, Tennessee; and Massena, New York; blast locks in the Ohio River between Louisville, Kentucky, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and wreck a Cryolite plant in Philadelphia.

Team No. 2 would be under the command of Edward Kerling, and his companions would be Haupt, Neubauer, and Thiel. It was to cripple the Pennsylvania Railroad by blowing up its station at Newark, New Jersey, and Horseshoe Bend near Altoona, Pennsylvania; disrupt facilities of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroads; send New York City’s Hell Gate railroad bridge crashing into the East River; destroy the canal and lock complexes at St. Louis, Missouri, and Cincinnati, Ohio; and demolish the water-supply system in greater New York City, concentrating on suburban Westchester County.

The Nazi saboteurs were to make no effort to conceal the fact that they were on a violent rampage in the United States. They were to constantly seek opportunities to blow up public buildings in order to promote panic.

On direct orders from Führer Adolf Hitler no expense was to be spared in Operation Pastorius. When preparing to board the two submarines at the German base at Lorient, France, Lieutenant Kappe had doled out a small fortune of $175,000 (equivalent to about $2 million in the year 2002) to pay bribes to accomplices and for other needs.

Once the sabotage network was established, Walter Kappe himself would slip into the United States as a sort of German supreme commander for boomand-bang operations. His headquarters would be in Chicago, a city he knew well. He would keep in contact with and issue orders to his scattered bands of saboteurs through coded advertisements in the Chicago Tribune, a large circulation newspaper.

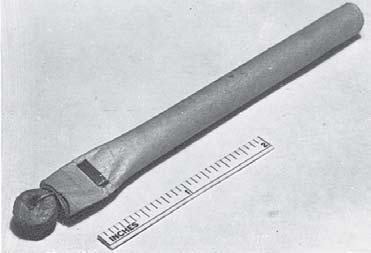

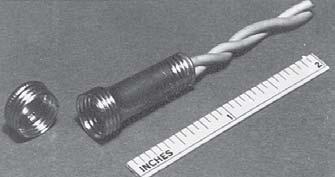

Now, on the deserted shores of Long Island and Florida the eight Pastorius saboteurs—four in each team—buried their marine uniforms. They distributed among themselves ingenious sabotage devices: bombs disguised as lumps of coal and wooden blocks, special timing gadgets, TNT carefully packed in excelsior, rolls of electric cable, a wide array of fuses, and incendiary bombs that looked identical to pencils and fountain pens.

Hardly had Team No. 1 landed in the murky fog than George Dasch glanced around and felt a surge of alarm. Coming toward the four intruders was the muted glow of a flashlight, carried by twenty-one-year-old Coast Guardsman John Cullen. Unarmed, he was making a routine beach patrol.

Seaman Second Class Cullen, too, had grown alarmed and stood glued to the spot. In the darkness, he could discern several men talking excitedly—in German. Dasch grabbed the sailor’s arm and snapped, “You got a mother and father, haven’t you? Wouldn’t you like to see them again?” Then the saboteur thrust a wad of currency into the startled Cullen’s hand. “Take this and have a good time,” Dasch said. “Forget what you’ve seen here.”

Cullen sensed that he had stumbled onto some sinister venture that was far beyond his ability to cope. Step by step he backed off, then whirled and raced away.

Back at the Amagansett Coast Guard station, the excited Cullen roused four of his mates and rapidly told them of his encounter on the fog-shrouded beach. The others were skeptical: no doubt Cullen was pulling a trick to relieve the lonely monotony. Then Cullen showed them the wadded bills— $265 worth—that Dasch had thrust into his hand. Now fully awake, the four Coast Guardsmen armed themselves and, along with Cullen, rushed to the site of the confrontation. There they uncovered the cache of explosives and the German uniforms.

Meanwhile, Dasch and the other three saboteurs caught a Long Island Railroad train to New York City. There they split. Dasch and Burger checked into the Governor Clinton Hotel on West 31st Street, while Heinck and Quirin registered at the Martinique.

Soon after Dasch and Burger reached their hotel room, Dasch said that he planned to notify the FBI of Operation Pastorius. “If you don’t agree, I’m going to kill you!” Dasch explained, pointing a pistol at his crony’s head. Burger assured the team leader that he had no objection.

They Came to Blow Up America

79

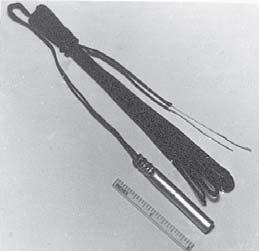

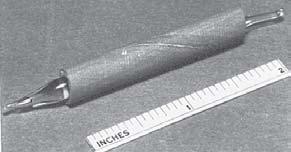

Capsule containing sulphuric acid encased in rubber tubing for protection.

Tools brought ashore by Operation Pastorius saboteurs. (FBI)

Early the next morning Dasch took a train to Washington. At 10:15

A.M.

on June 19—one week after Team No. 1 had come ashore—Dasch telephoned FBI headquarters. “My name is George John Dasch, and I have landed in a German submarine and have important information,” he stated. “I am in room 351 at the Mayflower Hotel.”

Within minutes two G-men arrived and listened in amazement as the former New York City waiter, in the vernacular of the U.S. underworld, sang like a canary. Every two hours, for two days, a fresh stenographer arrived at room 351 to record the incredible story of the Nazi saboteurs who had come to blow up America.

Dasch disclosed the U.S. industrial and transportation targets, described each of the other seven saboteurs in detail, and gave the names and addresses of their likely contacts.

Meanwhile, the seven members of Team No. 1 and Team No. 2 still on the loose scattered to cities across the eastern United States. But fourteen days after the intruders had landed, all had been collared by the FBI.

Five days later, on July 2, President Franklin Roosevelt appointed a military tribunal to hear the case, the first one of its kind in the United States since the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865. During the secret trial, all eight defendants swore that it had never been their intention to commit sabotage and that they had volunteered for the mission as a ploy for getting back to their loved ones in the United States.

All the dark invaders were found guilty, and on August 8 they were sentenced. George Dasch received a term of thirty years in prison, and Ernest Burger was given a life term. At noon the other saboteurs were electrocuted and buried in unmarked graves on a government plot in Washington.

8

Artillery Confrontation in Oregon

W

HILE MUCH OF THE NATION’S FOCUS

was on Nazi hijinks in the eastern United States, a Japanese submarine, the I-25, surfaced about 20,000 yards offshore from Fort Stevens, a complex at the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon. It was just after darkness had settled in on June 21, 1942.

At its leisure, the submarine’s crew fired some twenty rounds up and down the beach, perhaps seeking out Battery Russell, an artillery outfit equipped with ten-inch guns built in 1900. Colonel Carl S. Doney, battery commander, did not order the fire to be returned: His ancient weapons would fire only 16,000 yards. Bright orange flashes would have given away the unit’s position.