The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (11 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

The FBI and the OSS Feud

D

URING THE EARLY MONTHS OF 1942,

William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, a wealthy Wall Street lawyer and Congressional Medal of Honor recipient in World War I, dashed about Washington and New York City like a demon possessed in a search of recruits. A few weeks before Pearl Harbor, Donovan had been appointed by President Franklin Roosevelt to a new post: Coordinator of Information (COI).

It was a deliberately vague title. Roosevelt, a consummate politician, had privately instructed Donovan to launch political warfare against America’s enemies, using the president’s unvouchered funds. Actually, Donovan was to be the nation’s first official spymaster.

Establishing the COI had been a landmark in U.S. history and was designed to fill a crucial need for a worldwide intelligence apparatus. In an often hostile and volatile world, the United States had been stumbling around without eyes and ears.

After Pearl Harbor, the energetic Donovan, who had connections worldwide, conducted a nonstop personal recruiting campaign for his fledgling cloakand-dagger outfit. At posh cocktail parties, in Wall Street law firm suites, in the cloistered halls of Ivy League universities, in multibillion-dollar banks and investment firms, and along countless byways and highways, the indefatigable spymaster gave his sales pitch.

Flocking to Donovan’s siren call was a strange mixed bag: multimillionaire bluebloods and union organizers, athletes and ministers, bartenders and missionaries, a former Russian general, a big-game hunter, a former advisor to a Chinese warlord, and professors. There were corporate executives, lawyers, editors, scientists, labor leaders, ornithologists, code experts, and anthropologists, wild-animal trainers, safe-crackers, circus acrobats, paroled convicts, and a bullfighter. Scores of rough-and-ready individuals were, as Donovan described

Hijinks on a Hospital Roof

49

them, “hell raisers who are calculatingly reckless, of disciplined daring, eager for aggressive action, and enjoy slitting throats.”

Understandably, two strong-willed men competing on the same turf— Bill Donovan and J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI—soon clashed. Their ongoing duel intensified in mid-January 1942, six weeks after Pearl Harbor. No doubt Donovan privately approved a caper in which his agents “penetrated” (that is, broke into at night) the Spanish embassy in Washington. The dark intruders busily photographed the top-secret codebooks and assorted official documents of Generalissimo Francisco Franco’s pro-Nazi government.

When Hoover heard about the intrusion on his domain he was furious but did not register a formal complaint with President Roosevelt.

Three months later, Donovan’s boys paid another nocturnal call at the Spanish embassy to practice their photographic skills. They were tailed to the site by FBI agents in two unmarked cars.

Waiting while the intruders broke into the building, the FBI men pulled their vehicles in front of the embassy and parked. A few minutes later, the G-men turned on their sirens, whose strident sounds pierced the black stillness.

For blocks around, citizens dashed into the streets to determine the reason for the shrill noise. Was Washington about to be bombed by German planes?

Then the FBI cars sped away, just before the “burglars” scurried hell-bent out of the embassy.

Learning of the squabble between two of his elite agencies, President Roosevelt issued strict orders that implied the “legal burglary” of embassies in Washington was to be the sole domain of the FBI.

Donovan reportedly accepted the executive decision with a shrug, and continued to expand his agency, whose name would be changed to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

The new designation stirred up the fussing-and-feuding pot. The U.S. Army’s chief of intelligence refused to even speak to a reserve officer and communicated with Donovan through an intermediary when absolutely necessary. Hoover and the head of the U.S. Navy intelligence were embroiled in a squabble of their own, but each managed to find time to take potshots at Wild Bill and his fledgling OSS.

12

Hijinks on a Hospital Roof

S

HORTLY AFTER PEARL HARBOR,

Navy Lieutenant Commander John “Pappy” Ford set up a small temporary office in Washington. A famed Hollywood movie director, Ford had been acclaimed with Academy Awards for such blockbusters as The Grapes of Wrath, Stagecoach, Young Mr. Lincoln, and How Green Was My Valley.

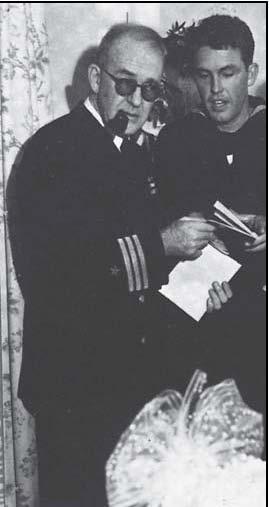

Famed Hollywood director John “Pappy” Ford (left) and a top assistant, Robert Parrish. Ford headed an OSS combat intelligence unit. (Courtesy of Robert Parrish)

Back in mid-1940, with America starting to partially mobilize in the wake of the threat of Adolf Hitler’s powerful military juggernaut, Pappy Ford, then forty-five years old and holding the reserve rank of Navy lieutenant commander, formed Field Photographic, an ad hoc unit without official Navy status. He signed up some of the biggest names in Hollywood: cameramen, sound-men, special effects, film editors, and script writers.

Ford organized his talented cinema civilians into a martial-type unit, taught them the basics of military discipline, then tried tenaciously to get Washington naval brass to absorb Field Photographic into the official reserves. For more than a year, Ford pleaded his case, but he was given the cold shoulder.

Ford was about to give up on his crusade as a lost cause when, just before Pearl Harbor, lightning struck from an unexpected source. Field Photographic was swept up intact by Bill Donovan, who felt that the moving-picture unit would be a valuable tool for cloak-and-dagger operations.

A few weeks later in Washington, Commander Ford called in two of his young petty officers, Robert Parrish and Bill Faralla, who had labored in the vineyards of the Hollywood movie industry. Ford instructed them to test a new type of combat camera that had been developed by Ray Cunningham, a technician at RKO Studios. The revolutionary moving-picture camera was mounted on a .30-.30 rifle stock; all the photographer had to do was point the camera and squeeze the trigger.

Hijinks on a Hospital Roof

51

Rising from his desk, Pappy Ford spit in the direction of a wooden box he kept in the corner for that function, lit his pipe, and said to Parrish and Faralla, “Give me a complete photographic report on the State Department Building next to the White House. Cover it from all angles, outside, inside, what have you. Don’t take any crap from anyone. If they give you a hard time, show them your OSS card.”

Parrish and Faralla, wearing their navy uniforms, entered a hospital across from the White House, climbed up stairs to the roof, and were accosted by a nurse. “Who are you men and what are you doing here?” she demanded to know, suspiciously eyeing the gunlike camera and other paraphernalia the strangers were carrying.

“We’re here on official business, Ma’am,” Parrish responded as Faralla flashed his OSS card. “We’re from the OSS.”

“Oh, yes,” the nurse replied. “The OSS. Well, continue with your work.” Faralla and Parrish were convinced that the dedicated nurse had no clue as to what OSS even stood for, much less what its function was. They set up a tripod, attached the odd-looking camera to it, and aimed what appeared to a marine on the roof of the State Department Building to be a machine gun. The sentry waved furiously, but the pair kept shooting moving pictures, including footage of a World War I machine gun “guarding” the White House.

Glancing back toward the State Department roof, Parrish froze as he saw a squad of marine reinforcements point their old bolt-action rifles at the unknown intruders on the hospital roof. With their first “combat photography” under their belts, Parrish and Faralla surrendered.

Parrish and Faralla were ensconced in a “detention chamber” in the subbasement of the State Department Building. There they remained incommunicado, from 4:30

P

.

M

. on Sunday until Tuesday at 11:00

A

.

M

. They were handled much as espionage suspects would be. Guards confiscated their OSS cards (“We never heard of no OSS,” one explained), the expensive combat camera (which was closely inspected for German and Japanese markings), and personal belongings.

Parrish kept telling the marine captain that the two men had been on a mission for Lieutenant Commander John Ford, the famous Hollywood director. The marine was unmoved. He said the suspects would remain until the camera-gun (as he called it) had been checked out by ballistic technicians. The film had been sent to other authorities to be developed and scrutinized.

Presumably John Ford had not been notified that two suspicious men claimed to be working for him because it was more than forty hours before Tom Early, a top aide to OSS boss Bill Donovan, arrived at the “jail.”

Faralla and Parrish were relieved to know that the visitor was the brother of Stephen Early, President Roosevelt’s press secretary. Hopes were quickly dashed. Tom Early advised the detainees that the marine captain was insisting that they be court-martialed by the Navy.

Finally, Commander Ford got into the act. He told the marine that his two men were only doing their jobs. “I think we should lock their film in a vault and dismiss any charges,” Ford declared. “Do you agree, Captain?”

After pausing briefly, the marine replied, “I agree, Commander.”

Bob Parrish and Bill Faralla were free men again.

Pappy Ford and Bill Donovan had hit it off from the beginning; each was a rugged individualist with a touch of the maverick in him. They would have been failures as diplomats for each said precisely what was on his mind. In mid-1942, Donovan called a meeting at OSS headquarters in Washington for precisely 8:00

A.M.

Hard-driving, hard-drinking Ford had been carousing the city until daylight, and when he walked silently into the conference room, his eyes concealed behind dark glasses, the others had already taken their seats.

“Commander Ford,” Donovan barked. “If you can see well enough, we’ll get started!”

“General,” Pappy replied evenly, “I can see one thing—you’ve got that ribbon for your Congressional Medal of Honor on the wrong place on your uniform!”

Donovan joined in the chorus of laughter.

13

Suspicions Run Rampant

I

N FEBRUARY 1942,

rumors continued to deluge home-front America. People in southern Florida spread the word that a German submarine captured offshore had a galley (kitchen) with milk bottles from a Miami dairy. Never mind that no German submarine had been captured. The tale was too good not to pass along. For many weeks home-delivery drivers from this dairy were the subjects of much suspicion—even scorn.

A good story can always stand elaboration, so in a variation of the Miami dairy yarn word raced through Virginia that bread from a Richmond bakery had been found on the “captured” U-boat.

No matter how absurd, these rumors were tracked down and deflated by the overburdened Federal Bureau of Investigation. But the probes did little, if anything, to shut off the rumor mills.

14

“German Officers” Stalk Harbor

S

UBVERSION WAS ON THE MINDS

of newspaper editors, and much ink was devoted to warn the public to be on the lookout for “suspicious persons.” Hoping to dramatize the lax security at war plants (and to sell more newspapers), two Philadelphia reporters donned the uniforms of officers of the Kriegsmarine (German Navy), complete with swastika armbands. It was early February 1942.

Commercial Radio’s First War

53

For the most of one day, the reporters stalked up and down the Philadelphia docks, stopping on occasion to point at a U.S. Navy ship and speaking with thick German accents. Not once were they challenged. The only time they received “official” attention was when a Philadelphia policemen told them that their automobile (a prewar German make) was parked illegally. When he saw that they were “navy boys,” the policeman did not give them a parking ticket.

15