The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (6 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

The RCAC operators contacted the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which sent an agent to the station. “Wish you’d monitor that wave length when you have time,” the G-man said. “If you hear anything, give us a call.”

About noon five days later, one of the operators telephoned the FBI man. “That station is sending again,” he said. “Sounds like a mobile marine unit at 6908 kilocycles, and it could be close to shore.”

Several FBI agents rapidly put in telephone calls to the Pan American Airways Station at Treasure Island, in San Francisco Bay, and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) monitoring stations at Portland, Oregon,

Rounding Up Subversive Suspects

21

and Santa Anna, near Los Angeles. These facilities were asked to tune in and take a directional reading on the mystery station. The telephone lines were held open.

In less than five minutes, the operator in the Pan American post said over the telephone lines: “According to my charting, that offshore station is sending from about eight miles off Point Mendocino, which is about two hundred miles northwest of here.”

The FBI agent immediately telephoned the information to the Pacific Naval Coastal Frontier headquarters, which promptly relayed the data to the PBY (amphibious airplane) on patrol.

Ten minutes later the navy post called back to report receipt of a message from the PBY: “Attacking enemy submarine.”

Two bombs were dropped, one landing behind the submarine and the other ahead of it. Then Army bombers arrived and dropped several depth charges on the now submerged submarine. Minutes later a large oil slick rose to the surface and spread over the water.

Men in the Army bombers felt they had destroyed the underwater vessel. But its fate would never be known for a certainty. As for the G-men who had worked on the case, they liked to think that they had played a key role in the destruction of a Japanese submarine.

15

Rounding Up Subversive Suspects

M

ONTHS BEFORE WAR ERUPTED

in the Pacific, J. Edgar Hoover, the peppery director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, had been getting his agency prepared for emergency operations. Now he put the FBI on a twenty-four-hour schedule. Annual leaves were cancelled. The entire force was faced with its greatest challenge—rapidly rounding up a few thousand subversive suspects from a list put together in recent months.

Prior to late 1939, when Hoover was designated by President Roosevelt to take sole control of the battle against spies and saboteurs, the United States had been a subversive’s paradise. Spies and saboteurs could and did roam the nation at will.

During the 1930s, Adolf Hitler’s espionage apparatus had invaded America with the most massive penetration of a major nation that history had known. Nazi agents stole nearly every military, industrial, and government secret. Hoover and his men had nailed scores of spies, but there were a large number still burrowed into the fabric of American society.

With the invasion of America’s West Coast a distinct threat in the early weeks of the war, Hoover was especially concerned that the Tokyo warlords had received a massive amount of military and industrial secrets obtained by

Lieutenant Commander Hideki Tachibana, who had projected himself as a language officer in the Japanese consulate in Los Angeles.

Back in May 1941, the FBI reported to Secretary of State Cordell Hull, who had been born in a log cabin in the Tennessee mountains, that G-men had uncovered widespread espionage activities by Tachibana. His diplomatic post had allowed him to travel up and down the West Coast unchallenged.

Hull gave the green light to arrest Tachibana, and he was taken into custody. A few days later the new Japanese ambassador to the United States, Kichisaburo Nomura, pleaded with Hull to release Tachibana in the interest of promoting good relations between the two governments.

For whatever the reason, Hull, who no doubt had the approval of President Roosevelt, agreed to free the Japanese spy, who was promptly deported. No doubt he took with him a huge cache of American secrets.

Now, after the G-men around the nation had been put on the alert, they waited impatiently for the order. From San Francisco, Special Agent in Charge

N. J. L. Pieper telephoned Louis Nichols, an assistant FBI director in Washington, and said: “The boys are getting jumpy. Shouldn’t we get going?” “Not yet,” Nichols replied. “We’ve got to wait for the proper papers to be signed after President Roosevelt issues an emergency proclamation.”

In the meantime, Director Hoover, rated in public opinion polls as the second most popular American (just behind Roosevelt), had turned his office suite in the Justice Department Building into a militarylike command post. When the green light came from the White House, Hoover leaped into action. Hour after hour, he barked orders on the telephone as his agents fanned out across the nation and Hawaii, Alaska, and Puerto Rico.

Assisted by local police, sheriffs’ departments, and military intelligence officers, the G-men moved with speed and coordination. Within the first seventy-two hours after Pearl Harbor, 3,846 subversive suspects were taken into custody. Each had a hearing before a civilian board and was represented by a court-appointed lawyer.

16

A Feud over Wiretapping

A

LTHOUGH CONFRONTED BY

the most serious threat in America’s history, squabbles over jurisdiction broke out after President Roosevelt designated the FBI to “take charge of communications censorship.” J. Edgar Hoover promptly put a halt to all communications to Japan.

Federal Communications Chairman James J. Fly and his aides were outraged over what they considered to be an intrusion onto their bailiwick. Fly fired off a message to the communications companies, calling on them to ignore the FBI order. However, Fly’s order was ignored.

Mission: Halt Ambassador’s Hara-Kiri

23

Hard on the heels of that brouhaha, the FCC and the FBI got into another fuss over the FBI’s right to make security checks (that is, wiretaps) on messages being sent to Tokyo, Rome, Berlin, Moscow, and other world capitals. Hoover maintained that it was the responsibility of his agency to make these checks, because Roosevelt had designated the FBI to be in charge of security on home-front America.

Curiously, with the United States at war, Chairman Fly and his FCC bureaucrats held that wiretapping or interception of messages was illegal, an interpretation of the law not shared by Attorney General Francis Biddle, who was Hoover’s boss, and legal experts in the Justice Department. Biddle’s view was that authorized wiretaps and intercepts were legal as long as the information obtained was not divulged to unauthorized persons.

Friction intensified when Fly and the FCC refused to turn over to the FBI the fingerprint cards of some 200,000 radio operators and communications employees. Fly pointed out that the prints had been taken only to check the citizenship of the workers and that turning over the prints might be regarded by the people fingerprinted as a serious breach of faith on the part of the FCC. Besides, Fly stated, the workers’ union leaders objected to the transfer.

Attorney General Biddle fired off a sharp letter to Fly. “The evidence is strong that messages have been surreptitiously transmitted to our enemies by radio [from the United States],” Biddle stated. “Military attacks upon the territory of this country may have furthered and facilitated thereby. . . . I should hate to have something serious happen which might have been easily avoided.”

Fly continued to balk. The cards should not be kept in FBI files because “it would be unfortunate if the employees were subjected to disclosure of past misdemeanors and other crimes that had nothing to do with national security matters.”

Biddle was unmoved. “If there is anyone in a position to do real harm in the present states of affairs, certainly the radio operator is included,” he responded to Fly. “Unless the cards are filed with the FBI, a person could be discharged for subversion by one federal agency and hired by another with no one the wiser.”

Months later the FBI received the fingerprint cards from the FCC. No doubt President Roosevelt himself had intervened in the dispute.

17

Mission: Halt Ambassador’s Hara-Kiri

I

N WASHINGTON,

Assistant Secretary of State Breckenridge Long was charged with containing the diplomats who were in the Japanese embassy when war broke out in the Pacific. If furious Americans were to break into the building and kill Ambassador Kichisaburo Nomura, U.S. diplomats waiting repatriation

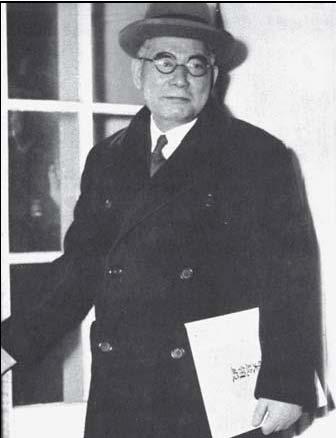

Japanese Ambassador Kichisaburo Nomura was reported to be planning hara-kiri while in U.S. custody. (National Archives)

in Tokyo might also be murdered. Consequently, heavily armed law enforcement officers guarded the Japanese embassy around the clock.

Ambassador Nomura and his staff had been trapped in the building for the first week after Pearl Harbor. The warlords in Tokyo had kept Nomura in the dark about the sneak attack, so such provisions as food soon ran out. A staff member telephoned for groceries and paid the deliveryman with a check. Soon the American was back with the check. Banks would not accept it. So forty people in the embassy pooled U.S. currency to pay the bill.

There were sleeping accommodations for only ten people, but four times that number were holed up in the embassy. So most of them had to sprawl on the floor at night without blankets or mattresses.

After the eight days of confinement, the Japanese delegation was moved to West Virginia and Virginia, where they were ensconced in luxury resort hotels to await an exchange for Americans in Japan.

A few days later Breckenridge Long received an alarming report: Nomura was preparing to commit hara-kiri, the historic ritual in which disgraced Japanese kill themselves.

Accelerating Long’s problem in dealing with his potentially explosive situation was the fact that the media got hold of the report and began speculating in print and on the air. Could the suicide be performed on foreign soil, or did it have to be done in Japanese controlled territory?

In this thorny situation, Long called on Charles Bruggmann, the Swiss minister in Washington, to intervene. He was a fifty-two-year-old career diplo

A Field Marshal Is Shocked

25

mat who was married to the sister of Henry A. Wallace, the vice president of the United States. The Swiss had met Mary Wallace in Washington and the couple was married the next year in Paris.

Unbeknownst to Breckenridge Long (or anyone else in Washington) Bruggmann had dispatched a series of telegrams to Bern, Switzerland, after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. These messages described in detail what had transpired in President Roosevelt’s office on the afternoon of December 7.

Bruggmann told Bern that the U.S. fleet was a twisted, smoking mass. This fact was to be kept from Japan. However, copies of the communications were stolen and sent on to Berlin by a German agent (code named Habakuk) who had been planted a year earlier in the Swiss Foreign Ministry in Bern.

Habakuk advised his superiors in Berlin that the information about the destruction of the U.S. fleet had to be authentic, because, he pointed out, Vice President Wallace had to be the source.

Within hours, Berlin flashed the high-grade intelligence to Tokyo. For the first time, the Japanese warlords knew that their sneak strike had been a rousing success.

Now, in Washington, Bruggmann was driven to the resort hotel where he pleaded with Ambassador Nomura not to kill himself because that action would cause grave consequences for many people. The Swiss might as well have saved his breath. Nomura soon made it clear that he had no intention of committing hara-kiri.

18

A Field Marshal Is Shocked

C

HRISTMAS 1941 WAS NEARING WHEN

Field Marshal John Dill arrived in Washington to take up his new duties as British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill’s liaison officer to the U.S. War Department. Accustomed to many months of wartime austerity in Great Britain, Dill was flabbergasted by the prosperous lifestyle of Americans and by the belief in official Washington that the Japanese and Germans could be quickly polished off without undue disruption of normal conditions on the home front.