The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (10 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

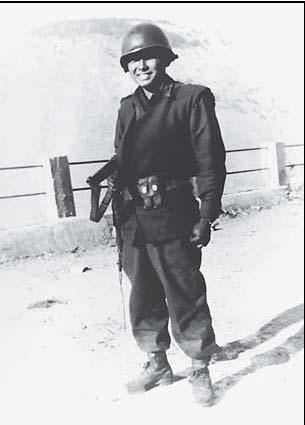

A “dangerous subversive” looks in bewilderment at an armed guard. No incident of betrayal by Japanese Americans ever occurred. (U.S. Army)

out to be false rumors seeped out that Japanese civilians in the Hawaiian Islands had pinpointed targets for the air armada.

Americans reacted with a gut impulse for revenge, and erupted in a rage against General Hideki Tojo, the warlord, and the Japanese nation as a whole. In their fury, American civilians turned on some of their own neighbors and fellow citizens—the 125,000 men, women, and children of Japanese birth or descent who lived in the continental United States. Nearly all of them resided on the West Coast, mainly in California. Some 70,000 had been born on U.S. soil, a fact that made them bona fide citizens.

In the shock and terror that followed the debacle at Pearl Harbor, General John DeWitt, in charge of West Coast defenses (which were virtually nonexistent), snapped: “A Jap’s a Jap! It makes no difference if he is an American or not!”

DeWitt had plenty of company. Milkmen refused to deliver their products to Japanese Americans (known as Nisei); grocers refused to sell them food; insurance companies cancelled their policies. The state of California revoked their licenses to practice law or medicine.

At first, the Japanese Americans were encouraged to leave California voluntarily and go inland to other states. Some eight thousand Japanese Americans followed the suggestion, thereby triggering angry voices from politicians and the media.

“If the Japs are dangerous in California, they are likewise dangerous in Nevada,” declared the Nevada Bar Association. Said Governor Chase Clark of Idaho, “I don’t want them taking seats in our universities.”

“Japs are not wanted or welcome in Kansas,” said Governor Payne Ratner, who ordered the state patrol to bar them from using the highways.

The thousands of wandering Japanese Americans were harassed at every turn. Many restaurants refused to serve them and ordered them out. Some eating places hung signs in their windows that read: “We poison rats and Japs.” Gas station employees wouldn’t fill their tanks with fuel. Small town cops threw some of the refugees in jail for “loitering” or as “suspicious subjects” before releasing them the next day.

In the weeks ahead, angry voices were raised across the United States, a resounding chorus demanding that every man, woman, and child of Japanese descent be evacuated from the West Coast. Perhaps the most powerful voice was that of Walter Lippmann, whose syndicated columns on politics and foreign affairs were carried in hundreds of newspapers.

Harvard-educated Lippmann may well have been the nation’s most influential journalist. It was said that Washington politicians read his columns as though Moses had brought them down from the mountain. Among Lippmann’s most ardent fans was President Franklin Roosevelt.

In those confused early days of the war, Lippmann wrote a strident column:

It is a fact that the Japanese navy has been reconnoitering the

Pacific Coast. . . . It is a fact that communication takes place

between the enemy at sea and enemy agents on land.

I submit that Washington [meaning President Roosevelt] is not

defining the problem on the Pacific Coast correctly and that it is

failing to deal with the practical issues.

The Pacific Coast is officially a combat zone; some part of it

may at any moment be a battlefield. Nobody’s constitutional rights

include the right to reside and do business on the battlefield.

Lippmann had substituted rumor and theory for facts. Never had there been any known incident of anyone on the Pacific Coast signaling Japanese submarines offshore.

Other influential voices joined the evacuation cacophony, including California Attorney General Earl Warren and Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau.

J. Edgar Hoover, the Federal Bureau of Investigation chief, strongly opposed the mass upheaval, describing any such action as being “a capitulation to public hysteria.” Hoover told Morgenthau that arrests should not be made “unless there are sufficient fact [probable cause] upon which to justify the arrests”; that the rights of American citizens should be protected.

“We Poison Rats and Japs”

45

Hoover was a voice crying in the wilderness. No doubt responding to demands from influential public sources and segments of the media, President Roosevelt, on February 19, 1942, signed Executive Order No. 9066. It authorized Secretary of War Henry Stimson to “establish military areas” on the West Coast and “exclude from them any and all [suspicious] persons.”

The ink had hardly dried on Roosevelt’s order than a mass evacuation of Japanese civilians and Nisei began. They were given forty-eight hours in which to dispose of their businesses, homes, and automobiles before reporting, with whatever belongings they could carry as hand luggage, to fifteen Army-run Assembly Centers, as they were officially designated.

On arrival, the detainees were given medical examinations and identification cards and herded into hastily thrown-up barracks. They were penned in by barbed-wire fences and constantly watched by patrolling Army military police. At night, searchlights swept the bare ground outside the wire.

Altogether, with brutal swiftness, 110,000 people—nearly the entire Japanese and Nisei community in the West—had been driven out of their homes and into virtual captivity.

Incredibly, almost without exception, the young men endured the internment and its humiliation with their faith in the United States unimpaired. Many of the Japanese Americans insisted that they be allowed to prove their loyalty to the United States by serving in frontline combat. One of them behind barbed wire, Henry Ebihar, wrote Secretary of War Stimson: “I only ask that I be given a chance to preserve the principles that I have been brought up on and which I will not sacrifice at any cost. Please give me a chance to serve in your armed forces.”

In response to the clamor from the young men in the internment camps, Congress authorized the formation of an all-Nisei combat unit, and on January 28, 1943, the Army announced it would accept volunteers. Some twelve hundred signed up and eventually joined the newly formed 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Meanwhile in Honolulu, another Nisei, seventeen-year-old Daniel K. Inouye, graduated from McKinley High School, where he was an honor student, only four months after the Pearl Harbor catastrophe. Perhaps because of his youth, he was not regarded by older Caucasians as a suspected subversive or threat to the United States, although he received his share of snubs and insults.

The oldest of four children, Inouye was born in Honolulu. His father, Hyotaro, had immigrated to Hawaii as a child from a village in Japan, worked as a file clerk to support the family in what Daniel would later describe as “respectable poverty.”

Shortly after receiving his high school diploma, Daniel enrolled in the premedical program at the University of Hawaii. But he dropped out of college to enlist as a private in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, whose motto was “Go for Broke!”

Twenty-one-year-old Lieutenant Daniel Inouye, who would receive the Congressional Medal of Honor fifty years later for an action in which he was seriously wounded. (Courtesy Senator Daniel Inouye)

Mild-mannered, soft-spoken Dan Inouye proved to be a tiger in combat, a natural leader of men, and he was awarded a battlefield commission as a second lieutenant.

In late April 1945, Lieutenant Inouye was leading his platoon in an assault to capture a heavily fortified German position that included several machine guns and a company of grenadiers (infantrymen) in the Po Valley of Italy. A blistering firefight erupted. Swarms of bullets hissed and sang overhead.

Inouye began slithering toward three spitting machine guns. Moments later, a rifle grenade exploded next to him, and jagged chunks of red-hot metal tore into his right arm. Dazed, bleeding profusely, his arm hanging in shreds, the lieutenant continued edging toward the German force. Then bullets ripped into his stomach and legs.

Through superhuman effort, Inouye managed to pull a pin from a grenade, rise up and toss the lethal missile. It exploded in the midst of one machine-gun crew. Twice more he lobbed grenades, wiping out the other two automatic weapons. Then he collapsed, unaware that his feats had permitted his platoon to charge forward and seize that objective.

After a few weeks in Army hospitals in Italy, where doctors had saved his life, Lieutenant Inouye was flown to the United States and became a patient at the Percy Jones Medical Center in Battle Creek, Michigan. The facility focused on rehabilitation of seriously wounded soldiers. Two other patients there were Robert Dole of Kansas, and Phillip Hart of Michigan. None of these three maimed servicemen had any way of knowing that years later all would be serving together in Washington as U.S. senators.

Mysterious Malady on Ships

47

Inouye spent two years in Army hospitals, recovering from his wounds and from amputation of his right arm at the shoulder. During these long, lonely hours, he had plenty of time to ponder his future—if indeed a twenty-one-year-old Nisei veteran with one arm had a future.

Unhappy, morose, nearly despondent, and usually dependent upon others, Inouye tried not to think of tomorrow. Yet his thoughts came back to his role in the civilian world.

He pledged not to let his physical disability thwart him from achieving useful goals in the years ahead. So he decided to change career directions and go into law and politics, instead of becoming a physician.

9

Goal: Coalition of Africa and Japan

O

N FEBRUARY 28, 1942,

violent racial strife erupted in Detroit, a vital center for war production. At the Sojourner Truth housing project prospective Negro tenants were assaulted by white men armed with clubs, knives, and rifles. There were scores of injuries and more than one hundred arrests.

Two of the white men taken into custody were members of a hate group that had been distributing pro-Nazi propaganda in the project. However, the rabble-rousers igniting violence in the Detroit region were five black men. They included Robert Jordan, a West India native, whose goal was to form a coalition of Africa and Japan to dominate the world.

In Berlin, Adolf Hitler’s propaganda genius, Paul Josef Goebbels, used racial discord in the United States in the Nazi’s worldwide disinformation apparatus. The Sojourner Truth riot in Detroit triggered an enormous outburst of propaganda. Die Wehrmacht, the Nazi newspaper aimed at the German armed forces, published a full page of pictures on the Detroit violence.

10

Mysterious Malady on Ships

D

URING A THREE-WEEK PERIOD

beginning on March 1, 1942, a mysterious malady struck several cargo ships after they sailed out of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia bound for hard-pressed Soviet forces. Each vessel was making the dangerous trek separately.

The freighters were loaded with tanks, munitions, airplane parts, artillery pieces, and other war supplies. A few days out in the Atlantic, as though on cue, each ship foundered and was unable to continue to its destination.

Guns, tanks, and trucks broke loose, careened over the deck, smashed other war goods, and plunged into the heavy swells of an angry ocean. Crippled by the shifting loads, each vessel was forced to slow, and then turn around and head back to its home port. A few ships never made it.

One of the vessels, the SS Collmar, a sitting duck, was torpedoed and sunk with the loss of ten crewmen, as it limped along toward Philadelphia.

The National Maritime Union smelled Nazi skullduggery in American ports and launched an investigation. It was found that, in several instances, cotter pins had not been in place on the shackles holding the deck cargoes.

On March 26, Joseph Curran, president of the Maritime Union, testified before a House committee in Washington that the shifting cargoes had hardly ever been a problem in peacetime. “We, as seamen, have been sailing ships that carried heavy deck loads, sometimes as high as you could get them, and we never lost any of that cargo,” Curran declared. “We never had a problem with deck loads.”

11