The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (7 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

“This country is the most highly organized for peace that you can imagine,” Dill wrote to Field Marshal Alan Brooke, chief of the Imperial General Staff in London. “At present this country has not—repeat not—the slightest conception of what war means, and their armed forces are more unready for war than it is possible to imagine.”

Closing his gloomy analysis, Dill declared: “The whole organization belongs to the days of George Washington.”

19

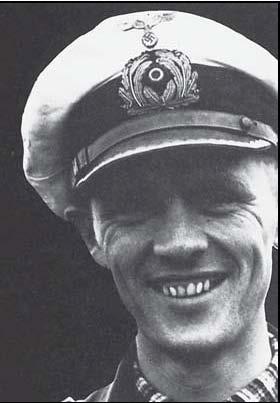

Lieutenant Reinhardt Hardegen took his U-boat into New York harbor early in 1942. Eventually his crew sank twenty-three Allied ships, most of them along the eastern seaboard of the United States. (National Archives)

Nazi U-Boat in New York Harbor

B

LOND, AUDACIOUS KRIEGSMARINE

(German Navy) Lieutenant Reinhardt Hardegen was steering his U-boat in the blackness toward New York harbor. It was January 13, 1942, the first day of Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat), a plan conceived and launched by Grossadmiral Karl Doenitz, chief of the submarine service. His goal was to blockade America’s Atlantic ports and cut her crucial shipping lanes to the British Isles.

Doenitz had selected Reinhardt Hardegen and eleven other bold U-boat skippers to stalk America’s eastern seaboard, directing Paukenschlag from the submarine base in Lorient, France. As reports flowed in from harbor spies in New York, Boston, Norfolk, and other eastern ports, the U-boat chief, like a chess master adroitly moving pawns, shifted his underwater wolves into position to intercept departing ships.

Now, at midnight, Lieutenant Hardegen’s U-123 surfaced off the port of New York. He and his crewman were astonished by the dazzling sight before them. Even though the United States had been at war for more than a month, Manhattan was aglow with thousands of lights that twinkled through the night like fireflies.

“It’s unbelievable!” Hardegen exclaimed to Second Officer Horst von Schroeter. To dramatize how close the U-123 was to America’s largest city, Hardegen quipped in a radio signal to Lorient: “I can see couples dancing on the roof garden atop the Astor Hotel in Times Square.”

With daylight approaching, the U-123 nestled silently on the ocean bottom of Wimble Shoal, a few miles south of New York City. Throughout the day, Hardegen’s radio man reported sounds of ships overhead. “Gott!” the skip

The Salesman’s Luck Runs Out

27

per exploded. “Can you imagine what we could do with twelve U-boats in here [New York harbor]?”

20

A Journalist Prowls the

Normandie

E

DMOND SCOTT, A REPORTER

for a New York City newspaper, PM, was assigned to a curious investigation. He was to masquerade as a longshoreman and look into repeated reports that the waterfront was wide open to sabotage. It was mid-January 1942.

Dressed in work clothes, Scott got a job with a crew hired to lug furniture aboard the French ocean liner Normandie at Pier 88 on the Hudson River. Taken over by the U.S. Navy and rechristened the Lafayette, the huge vessel was being converted into a badly needed transport, and some fifteen hundred civilian workers were swarming about on her.

Scott was appalled by the almost total lack of security for this highly valuable ship. A private firm had been hired to guard the vessel, and anyone who had fifty dollars for a union initiation fee could become a stevedore and board the Normandie.

Alone and unchallenged, the disguised Scott prowled all over the ship, and he was struck by how simple it would be to set fire to the vessel. A pocketful of incendiary pencils, he visualized, could be used with devastating impact.

Eight hours after “longshoreman” Scott had boarded the Normandie, he had learned her destination, when she would leave New York, how many guns she would mount, and the thickness of armor being put over portholes—secret information obtained from loose-tongued workers and foremen.

Back at his newspaper, Scott handed his blockbuster story to editors. They were flabbergasted, calling the account a “blueprint for sabotage,” one that could advise enemy saboteurs how to destroy the world’s third largest ship (only a few feet shorter than the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth). So publication was held up.

However, the alarmed editors did report Scott’s amazing adventure to Captain Charles H. Zearfoss, the U.S. Maritime Commission’s antisabotage chief. He angrily denied the findings (the editors would say) and ordered: “Get your reporter off there before he gets shot!”

21

The Salesman’s Luck Runs Out

T

HIRTY-SIX-YEAR-OLD

Waldemar Othmer led the life of the average young American. A blond, blue-eyed personable man, he supported his wife and son by selling Electrolux vacuum cleaners in and around Norfolk, Virginia, site of the Navy’s largest base and headquarters of the Atlantic Fleet.

Neighbors were fond of Othmer, who always had a kind word to say and took his family to church each Sunday. He had volunteered his services to the Red Cross and each day raised an American flag in front of his modest house. Neighbors noticed that Othmer often was gone for several days at a time, but they presumed he was selling vacuum cleaners. What they didn’t know was that he was a slick Nazi spy.

In 1937, Othmer, a naturalized American of German birth, had returned to the fatherland on a visit. Impressed by Adolf Hitler’s cause, he volunteered to spy in America. His German controller instructed him to “lay low” in the United States (a sleeper agent) until he was called to active duty. That summons came in 1940 when President Roosevelt began rearming the nation to counter the Nazi threat.

Othmer had been ordered to serve his espionage apprenticeship at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where he passed his test with flying colors. Later he obtained a job as a civilian electrician at a Marine Corps training base in North Carolina, and then he was told to establish a residence in Norfolk.

From his vantage point in the Virginia port—he often paid visits to the naval base without undue challenge—Othmer was able to pass on to his German controllers in Hamburg the status of American and British warships and merchant vessels being repaired there and when they sailed.

In 1943, Othmer’s days of betraying his adopted country came to a sudden halt. Arrested by FBI agents, he was tried in court, found guilty of espionage, and sentenced to twenty years in prison.

22

Part Two

America under Seige

Joe Louis Contributes Huge Purse

S

IX WEEKS AFTER PEARL HARBOR,

Joseph Louis Barrow did what no other boxer had done before or since: he risked a million-dollar-plus heavyweight championship to make a major financial contribution to his country. Known professionally as Joe Louis, the Brown Bomber, as he was called, was going to put his title on the line against a promising fighter, Buddy Baer. At two hundred and thirty pounds, the challenger would outweigh the champion by twenty-five pounds. In his bout against Baer, Louis would donate his $100,000plus purse (equivalent to $1.2 million in 2002) to Navy Relief for needy families of sailors.

Born to cotton-picking parents in tiny Lexington, Alabama, Louis had won the world title in June 1937 when he knocked out James Braddock in the eighth round in Chicago. Sports writers claimed Louis had the fastest hands ever for a heavyweight.

On the afternoon of the fight, the Navy held a luncheon, and Louis was asked to speak to the twenty-five-hundred guests. Poker-faced (as he always was during his fights) and soft-spoken, he said that he was going to join the Army. “We will win the war,” he added, “because we are on God’s side.”

That night the champion demolished Buddy Baer in the first round. The next morning Louis was sworn into the Army as a private.

1

A Grieving Father Joins Navy

O

N JANUARY 4, 1942,

fifty-one-year-old Walter Bromley called at a Seattle recruiting station and tried to enlist in the Navy. He was rejected. Six years too old.

Bromley persisted, and a few hours later the Navy recruiter was suddenly struck with blurry vision and he wrote on the application that Bromley was forty-five. Minutes later he was sworn into the service, possibly the oldest seaman in the Navy.

Bromley had explained that his two sons had been killed at Pearl Harbor.

2

31

Self-Appointed Do-Gooders

W

ITH THE BULK OF

America’s young men in uniform or about to enter the armed forces, do-gooders in the civilian sector took it upon themselves to stand guard over the morals of the GIs. The Minnesota Anti-Saloon League passed a resolution—unanimously of course—that called for the War Department to establish so-called “dry zones” around Army camps.

Church groups fired off letters to members of Congress about the evils of Demon Rum and demanded that prostitutes not be permitted any closer to military installations than five miles.

Other segments of American society, however, were not eager to “eliminate” prostitution around military bases—if such a goal actually could be achieved. Many leaders in the armed forces felt that young men required sexual activity, that the urge was uncontrollable. Large numbers of local government officials looked on prostitution as an industry that brought heavy revenue to the city halls.

In early 1943, headlines in the sensationalist press screamed that venereal disease had reached epidemic proportions around military bases and demanded that Washington take action to wipe out this plague.

No doubt responding to pressure from Congress, whose members were being bombarded with letters from worried mothers, Surgeon General Thomas Parren published a report that scalded armed forces leaders for not doing enough to halt the spread of venereal disease, which he called the “number one saboteur of our defense.”

Parren’s document gave detailed and lurid descriptions of “our country’s newly organized panzer prostitutes.”

Newspapers, even so-called staid ones like the New York Times, eagerly published long excerpts from the racy Parren report.

President Roosevelt, always the consummate politician, instructed the Army and Navy to take action to curb the nation’s “number one saboteur.” Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox responded by holding a private session with the House Committee on Naval Affairs, on February 23, 1943.

Knox, a former publisher of the Chicago Daily News, brought with him an article from the current issue of American Mercury, a small-circulation magazine, entitled: “Norfolk—Our Worst War Town.” The piece detailed how easy it was to obtain illicit liquor and sex in and around Norfolk, site of the nation’s largest naval base. In that Virginia city of some 200,000 population, the Navy had its largest supply depot and the headquarters of the Atlantic Fleet.

Immediately after the session with Knox, Naval Affairs Committee Chairman Carl Vinson appointed a seven-person panel, headed by Ed Izac, to rush to Norfolk and hold hearings. The only woman in the group was Margaret Chase Smith, whom the media promptly dubbed the Vice Admiral. Forty-five years of age, she had become a Republican member of the House in 1940.

A Hollywood Victory Committee

33

Smith sat at the end of a long table at the hearing in Norfolk, decidedly uncomfortable about being surrounded by only men and the topic—sex and whores. In that era, such gross subjects were not discussed in front of refined ladies.

Smith was deeply disturbed by the lurid disclosures. Norfolk officials testified that professional prostitutes were no longer the main source of venereal disease proliferation. Taking the place of the whores as the primary source of contagion were young girls, some only twelve to fourteen years of age.

Labeled “good-time Charlottes,” “patriotic amateurs,” or “khaki-wackies,” these girls, the Norfolk chief of police testified, were “unable to resist a man in uniform.”

Margaret Smith was horrified to learn of the steps being taken by law enforcement officers to “control” venereal disease around the naval base. Civilian curfews resulted in the arrest of women “with no visible means of support,” leaving it to the police officer to determine if the women were “promiscuous.”