The Battle of Midway (Pivotal Moments in American History) (52 page)

Read The Battle of Midway (Pivotal Moments in American History) Online

Authors: Craig L. Symonds

Tags: #PTO, #Naval, #USN, #WWII, #Battle of Midway, #Aviation, #Japan, #USMC, #Imperial Japanese Army, #eBook

Consequently, Nagumo now knew that there were two undamaged American carriers out there somewhere, and thus that there was no realistic hope of forcing a surface engagement. With only the

Hiryū

and its ten Kates, plus perhaps a score of Zeros, it was evident that it was now time—indeed past time—for the Kidō Butai to cut its losses and run for i.t Nevertheless, Nagumo approved Yamaguchi’s decision to send Tomonaga and the ten Kates out to do what they could.

One factor in that decision may have been that Admiral Yamamoto had at last put his oar in. He had considered breaking radio silence at 7:45 a.m. that morning, when the

Yamato

had picked up the report by Petty Officer Amari that there were ten American ships to the northeast. At the time, Yamamoto had turned to his chief of staff and said, “I think we had better order Nagumo to attack at once.” But in the end he had decided not to interfere, and now he very likely regretted it. At 12:20 Yamamoto broke radio silence to send a series of orders directing Kondō’s battleships and heavy cruisers to close on the Kidō Butai from the south and Kakuta’s two carriers off the Aleutians to abort their mission, send the transports back to Japan, and steam south. Rather than cut his losses, Yamamoto was prepared to double down in the hope of winning the pot. As for Nagumo, by dispatching Tomonaga’s handful of torpedo bombers against the Americans at 1:30, he had staked everything on their success.

21

When Tomonaga took off from the

Hiryū

, he knew that he would not be coming back. During the attack on Midway that morning, his left-wing fuel tank had been punctured and was no longer serviceable. Consequently, though he had enough gas to find the enemy, he would not have enough to return. He joked with his fellow pilots that with the Americans only ninety miles away, he would have enough fuel to make it, but everyone recognized it as bravado. Yamaguchi himself came down to the flight deck to shake Tomonaga’s hand and tell him goodbye, and to remind him that it was essential to find and cripple a second American carrier. One had been badly wounded, perhaps sunk, but there were two more out there.

22

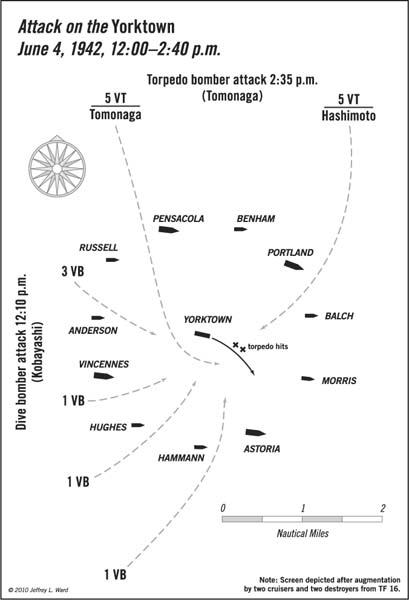

After leading his small squadron eastward for not quite an hour, Tomonaga saw the wakes of an American task force on the surface. At the center of that task force was an apparently undamaged carrier making an estimated twenty knots and launching aircraft. Clearly this could not be the cripple that Kobayashi’s dive-bombers had left dead in the water and burning only two hours ago. He used hand signals to indicate the target and split his ten planes into two divisions to conduct a classic anvil attack. Despite outward appearances, his target was indeed the

Yorktown

, returned to operational status by her efficient damage-control teams. Consequently, instead of hitting a second carrier, Tomonaga’s Kates were about to expend their fury on the same carrier that Kobayashi had hit, while the two carriers of Task Force 16 remained undiscovered and unharmed.

Tomonaga led one division of five planes against the

Yorktown

’s starboard side, while Lieutenant Hashimoto Toshio took the other five planes out to the left to attack its port side. As the Kates bore down on the

Yorktown

, Thach’s eight Wildcats were struggling to get airborne. The

Yorktown

’s own 5-inch guns had already started firing when the first of the Wildcats rolled down the deck, and the pilots could feel their jolting recoil as they took off. On the one hand this launch at the last possible moment was fortuitous because, with only twenty-three gallons of gas, the Wildcats were spared having to burn fuel flying out to the contact. On the other hand, it also meant that the air battle took place inside the envelope of the antiair fire from the escorts of the task force. That escort was even more powerful now than it had been two hours before, for Spruance had sent two cruisers

(Pensacola

and

Vincennes)

and two destroyers

(Benham

and

Balch)

to reinforce

Yorktown

’s screen. Consequently, Wildcats, Zeros, and Kates maneuvered and shot at each other from close range as thousands of rounds of ordnance flew past them from the screening cruisers and destroyers. It was like fighting an air battle in the middle of a target range.

23

One of the Wildcats was piloted by a 22-year-old ensign with the unlikely name of Milton Tootle IV, the son of a prominent St. Louis banker. Tootle’s plane had barely cleared the deck in his takeoff when he made a hard right turn and saw a Kate making its torpedo run on the

Yorktown

. Tootle did not even have time to crank up his landing gear before he fired a long burst at the Kate and shot it down. When he pulled up, however, he entered the free-fire zone of the

Yorktown

’s own antiaircraft battery, and his plane was hit by friendly fire. As his cockpit filled with smoke, he knew he was too low to bail out, so he climbed to 1,500 feet before jumping. His whole flight had lasted less than five minutes.

24

Jimmy Thach almost didn’t get airborne at all. He flew the only Wildcat that had been fully fueled, which made it heavier, and in the light winds, it virtually fell off the end of the flight deck; Thach had to nurse it up into the air. As he began to gain altitude, he too saw an enemy torpedo plane streaking in toward the

Yorktown

, and he turned to go after it. As he closed in, he saw that its tail bore “a bright red colored insignia shaped like feathers … that no other Japanese aircraft had.” It was Tomonaga’s command plane, flying very low, barely fifty feet off the water, and heading straight for

Yorktown

’s starboard side. Thach made a side approach and triggered a long burst of .50-caliber bullets. The Kate began to smoke, and flames issued from the engine, but Tomonaga somehow held his course. Thach recalled that “the whole left wing was burning, and I could see the ribs [of the plane] showing through the flames,” but still Tomonaga flew on. Thach was impressed in spite of himself. “That devil still stayed in the air until he got close enough and dropped his torpedo.” Only after that did Tomonaga’s plane smash into the sea and disintegrate. No doubt Tomonaga died satisfied that he had done his full duty. But despite his sacrifice, his torpedo missed, as did those of the other planes in his section.

25

Hashimoto’s second division had better luck. Threading their way through the heavy antiair fire, four of the Kates in his section managed to get close enough to launch their torpedoes. That morning, Petty Officer Hamada Giichi had watched the destruction of

Kaga, Akagi

, and

Sōryū

from the deck of the

Hiryū

and had resolved to make the Americans pay. Now, after his pilot dropped his torpedo and pulled out over the

Yorktown

’s flight deck, Hamada leaned out of the cockpit and shook his fist at it. The Americans who saw him yelled and gestured back. It was an intensely personal moment in a battle dominated by impersonal weapons. Within seconds, at 2:43 p.m., the first torpedo struck the

Yorktown

flush on the port side at about frame 90.

26

“It was a real WHACK,” Ensign John “Jack” Crawford remembered. “You could feel it all through the ship. … I had the impression that the ship’s hull buckled slightly.” The blast knocked out six of the ship’s nine boilers and opened a large hole in the hull fifteen feet below the water line. Fires spread into the other boiler rooms and knocked out all propulsion. The

Yorktown

began to slow and take on a slight list. Then, just moments later, a second torpedo struck near frame 75. The two strikes were so close together that combined they created a single giant sixty-by-thirty-foot hole in the

Yorktown

’s port side. The inrushing sea flooded the generator room and knocked out power throughout the ship; the emergency generators failed too, and the ship went dark. The

Yorktown

continued to lose way and the list became more pronounced. Soon she was again dead in the water. Eventually the ship heeled over at a 26-degree angle—so steep that it was difficult to walk on the flight deck. Commander Clarence Aldrich, the damage-control officer, reported to Buckmaster that without power none of the pumps feeding the fire hoses were working, nor could he effect counterflooding to prevent the

Yorktown

from listing further. Charles Kleinsmith, whose crew had kept boiler number one in operation after the first attack, had been killed. Lacking power, unable to fight the fires, and fearing that the big flattop “would capsize in a few minutes,” trapping the whole crew underwater, at 2:55, Buckmaster ordered abandon ship.

27

There was no panic. Men came up from the darkened spaces below, some carrying the wounded. The kapok-filled life vests were stowed in giant canvas bags suspended from the overhead on the hangar deck, and they spilled onto the deck in a heap. As they had on the

Lexington

in the Coral Sea, men stripped off their shoes for swimming and lined them up on the deck. Because Buckmaster feared the ship might roll over at any moment, he directed the men to evacuate from the starboard (high) side. From there, it was some sixty feet from the flight deck to the sea, and the men had to lower themselves down knotted ropes thrown over the side. One recent graduate of the Naval Academy began to lower himself with his legs splayed out at a 45-degree angle as he had been taught to do in gym class. Then, appreciating that this was not gym class, he wrapped his legs tightly around the rope as he continued his descent. Seaman E. R. “Bud” Quam successfully lowered himself down into the sea, then found that the water soaking into his heavy anti-flash overalls made them heavy and threatened to drag him down. He was floundering badly when a pair of strong arms pulled him out of the water and into a rubber raft. He looked up at his rescuer and was astonished to see that it was Peter Newberg, a high school classmate from Willmar, Minnesota.

28

Morale remained high, even in the water. Those bobbing in life vests put out their thumbs to those in the rafts, as if hitching a ride. A few called out “Taxi! Taxi!” and there was a lot of joshing and joking—one group began singing “The Beer Barrel Polka.” The escorting destroyers closed in to pick up the survivors, and eventually some 2,280 men were recovered; USS

Balch

alone picked up 725. Buckmaster wanted to ensure that he was the last one off the

Yorktown

. All alone, he conducted a tour of the spaces that were still above water to make sure that no one had been overlooked. With the

Yorktown

listing near 30 degrees and the decks and ladders slippery with oil, he had to move “hand-over-hand” to stay vertical. By now the water was lapping at the hangar deck. Buckmaster made his way to the stern, stepped off into the sea, and swam away from the ship. He was soon picked up and taken on board Fletcher’s new flagship, Astoria.

29