The Battle of Midway (Pivotal Moments in American History) (56 page)

Read The Battle of Midway (Pivotal Moments in American History) Online

Authors: Craig L. Symonds

Tags: #PTO, #Naval, #USN, #WWII, #Battle of Midway, #Aviation, #Japan, #USMC, #Imperial Japanese Army, #eBook

Spruance also got word of the two “battleships” west of Midway, and his task force now possessed a robust strike force of more than sixty bombers with the addition of Wally Short’s Scouting Five from

Yorktown

and the return of Ruff Johnson’s Bombing Eight from Midway. Spruance did not launch at once, however. Battleships were valuable targets but not as important as carriers, and another report at 8:00 a.m. indicated a crippled Japanese carrier off to the northwest. It was, in fact, the

Hiryū.

Despite the torpedo from the

Makigumo

that was supposed to have sunk her, the

Hiryū

continued to drift along, powerless but afloat. Moreover, forty or so men from the engine rooms who had been overlooked when she was abandoned had made their way up to the flight deck and were still on board. Spruance did not know any of this; all he knew was that there was still an enemy carrier out there, and he wanted to go get it.

The

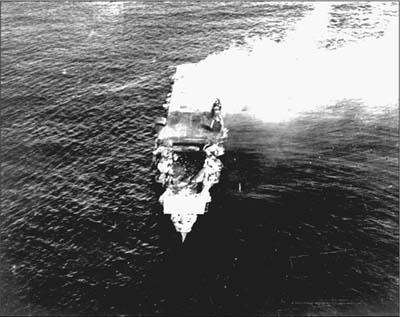

The

Hiryū

, as photographed by a scout pilot from

Hōshō

on June 6. When Yamamoto learned that the

Hiryū

was still afloat, he dispatched the destroyer

Tanikaze

to finish her off. (U.S. Naval Institute)

Yamamoto found out that the

Hiryū

was still afloat about the same time that Spruance did. At 7:20 that morning, a search plane from the small carrier

Hōshō

, which was accompanying Yamamoto’s Main Body, sent in a sighting report of the

Hiryū

, including the information that there were still men on board her who had waved when the scout plane flew past. The pilot’s backseat gunner took pictures of the crippled carrier, still smoking and with a gigantic hole in her forward flight deck, but on an even keel and in no apparent danger of sinking. Yamamoto was displeased, for now he had to order a destroyer to go back and rescue the men on the carrier and then ensure that the

Hiryū

was sent to the bottom. Ironically, as Spruance was pondering sending a force to find and sink the

Hiryū

, the Japanese destroyer

Tanikaze

was dispatched on a mission to accomplish precisely the same goal.

13

Conflicting sighting reports led Spruance to hold off from attacking immediately, and by the time these reports were sorted out, it was early afternoon. Another problem was that the sighting reports put the

Hiryū

some 230 miles away, and the need to turn away from the target into the wind to launch meant that it would be closer to 270 miles away by the time the strike force set out. Though this was well beyond the ideal range of the Dauntless dive-bombers, Browning wanted to launch at once. He pointed out that if Task Force 16 steamed toward the target during the outbound flight, it would reduce the length of the return trip. Moreover, he wanted all the planes to carry 1,000-pound bombs, which were unquestionably more effective than 500-pound bombs, but which significantly reduced the fuel efficiency—and therefore the range—of the bombers. The planes on

Enterprise

that would be assigned this task were mostly refugees from the

Yorktown

, and the two squadron commanders, Dave Shumway and Wally Short, were leery of lugging 1,000-pound bombs to a target more than 250 miles away. After talking it over between themselves, they decided to talk to the CEAG, Wade McClusky, who was down in sick bay recovering from his wounds of the day before. McClusky listened to their concerns and agreed that the order was unwise. He got out of bed to go with them back up to the bridge to see Browning.

14

Browning was annoyed at having his orders challenged. He was not only the senior aviator on board, in his mind he was the representative—in spirit, if not in fact—of the absent Bull Halsey, and he refused to reconsider. As McClusky put it, “Browning was stubborn.” Unintimidated by his blunt refusal, McClusky pressed the issue. He reminded Browning that most of the planes in his own squadron had run out of gas returning from their attack on the

Kaga

and

Akagi

the day before—and those targets had been only 170 miles away. He pointedly asked Browning whether he had ever flown an SBD carrying a 1,000-pound bomb and a full load of gas from a carrier deck. Browning admitted that he had not. McClusky then formally requested a one-hour delay in the launch in order to close the range, and, further, that the bomb loads on all the planes be changed to 500-pounders. Browning was starting to reject McClusky’s request when Spruance, who had been quietly listening nearby, interrupted him, saying evenly, “I will do what you pilots want.” Browning was furious to be publicly overridden. Without another word, he left the bridge and stalked off to his cabin. A contemporary likened it to Achilles sulking in his tent.

15

Spruance’s decision meant not only an hour’s delay in the launch but rearming all the strike planes with 500-pound bombs, which took additional time. As a result, the strike against the

Hiryū

was not launched until after 3:00 in the afternoon. The

Hornet

launched first—and this time Stanhope Ring made sure that he was not left behind. He led Walt Rodee’s VS-8 and Ruff Johnson’s VB-8 (plus one orphan from Wally Short’s VS-5), thirty-two planes altogether. At about the same time, Shumway and Short led thirty-three planes from the

Enterprise.

Thus a total of sixty-five bombers headed out to finish off the crippled

Hiryū.

Though none of them knew it, the

Hiryū

had already sunk, going down without any further assistance from either American bombs or Japanese torpedoes shortly after 9:00 that morning, less than twenty minutes after the last sighting had been called in. Stanhope Ring was bound on another “flight to nowhere.”

*

The Americans flew low in a long scouting line to ensure that they did not miss the target. When they reached the reported coordinates at twilight, around 6:00 p.m., “the enemy was nowhere in sight.” Grimly determined, Ring pressed on. At 6:20, he spotted a single vessel, initially identified as a light cruiser but which was in fact the destroyer

Tanikaze

bound on the same mission he was: to find and sink the

Hiryū.

Ring led his air group past the

Tanikaze

, looking for bigger game. After flying more than three hundred miles and seeing nothing, Ring decided to go back and sink that light cruiser. It was the first enemy ship he had seen since the battle began, and he was not going back this time without striking a blow. He reported the sighting to both Shumway and Short, and since neither of them had found a target either, all sixty-five American dive-bombers prepared to attack the hapless

Tanikaze.

Her captain, Commander Katsumi Tomoi, may have wondered what he had done to merit such attention.

16

Katsumi had been skeptical of his assignment from the outset. When ordered to return to the

Hiryū

, rescue her crew, and then sink her, he considered the mission “suicidal.” Now he announced to the crew on the ship’s loudspeaker that they “should be prepared to die with dignity.” At the same time, however, he was determined to make the best defense he could. He ordered lookouts to lean out the bridge windows, facing almost straight up, and to report the flight path of each approaching American bomber. They would call out, “Dive-bombers approaching from aft starboard!” and Katsumi would order the helmsman: “Port helm. Full speed.” When another dove from the port side, he reversed helm. “I never saw a ship go through such radical maneuvers at such high speed,” Ring later wrote.

17

In the gathering darkness, the American dive-bomber pilots jostled among themselves to attack this one lone destroyer. One by one, sixty-five American dive-bombers plunged down to release their bombs, and they pressed the attack to the limit—the lookout on the

Tanikaze

later recalled that the bombers dove so low he could see the pilots’ goggles and white scarves. In spite of that, all the American bombs missed. Whether it was the small size of the target, the gathering darkness, or Katsumi’s maneuvers, not a single bomb hit home.

*

Lieutenant Abbie Tucker of Ruff Johnson’s squadron managed a near miss that damaged the

Tanikaze

’s hull near the waterline, but that was it. Moreover, Sam Adams, perhaps still in his blue pajamas, was shot down by antiair fire. He and his backseat gunner, Joseph Karrol, were never found. Because Adams was an especially popular member of Short’s VS-5, this loss significantly dampened the mood on the return trip. Johnny Nielsen thought, “We

might better have lost a cruiser than lost Sam.”

18

Returning low on gas after a very long flight, the pilots now had to find the carriers in the dark, and most of them had never attempted a night landing, even in training. At 7:30, worried that the pilots didn’t have time to look for the task force, and knowing they would be low on gas, Spruance ordered both carriers to turn on their big 36-inch searchlights, pointing them straight up like beacons despite the danger of attracting the attention of Japanese submarines. The searchlights were turned off at 8:00, but the

Enterprise

kept her sidelights burning for another two and a half hours.

*

As a result, Adams was the only pilot who failed to return, though in the dark some of the pilots landed on the wrong carrier. Only after the strike force was back aboard did Spruance learn that several of the planes from

Hornet

had flown off with 1,000-pound bombs despite his orders to carry 500-pounders. He said nothing at the time, but the news added to a lengthening list of concerns he had about the

Hornet’s

performance in the battle, and about Mitscher’s capacity for command.

19

This time, instead of heading east during the night hours, away from the enemy, Spruance ordered the task force to maintain a westerly course, though he did so at a reduced speed, both to avoid running into Japanese battleships in the dark and to conserve fuel. Then he went to bed.

20