The Battle of Midway (Pivotal Moments in American History) (59 page)

Read The Battle of Midway (Pivotal Moments in American History) Online

Authors: Craig L. Symonds

Tags: #PTO, #Naval, #USN, #WWII, #Battle of Midway, #Aviation, #Japan, #USMC, #Imperial Japanese Army, #eBook

Marc “Pete” Mitscher

was never officially called to account for his error-plagued performance at Midway. Spruance knew that Mitscher’s report was flawed, however, and he very likely suggested to Nimitz that Mitscher should no longer command a carrier task force. After the battle, Nimitz transferred Mitscher to the command of Patrol Wing Two, a shore-based billet, and Mitscher remained there in a kind of exile until December. In April 1943 he became commander of air assets in the Solomons and gradually worked his way back into Nimitz’s good graces. In January of 1944 he received command of the Fast Carrier Task Force, called Task Force 58 since it was associated with Spruance’s Fifth Fleet. Based on his success in that role, he was promosted to vice admiral in March. With overwhelming superiority over the enemy, Mitscher emerged as “the Bald Eagle” and “the Magnificent Mitscher,” winning several decorations. After the war, he became the deputy CNO for Air, and then, as a four-star admiral, commander of the Atlantic Fleet. Mitscher’s health was never good; he died in February 1947 at the age of 60 while still on active duty.

Miles Browning

’s postbattle career was as rocky and uneven as his performance at Midway. Aware of Browning’s many lapses during the battle, Spruance did not recommend him for a medal. When Halsey returned to active duty that fall, he made up for it by putting Browning in for a Distinguished Service Medal. The citation claimed that Browning was “largely responsible” for the American victory at Midway, an assertion that some historians have taken seriously but which is manifestly untrue. Halsey brought Browning back onto his staff, but after problems continued during the Solomons campaign, including a messy and public affair with the wife of a fellow officer, Secretary of the Navy Knox insisted that he be replaced. Browning got another chance as the commanding officer of the new-construction USS

Hornet

(CV-12), a replacement for the original

Hornet

(CV-8) which was lost in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands in October 1942. Once again, however, Browning’s volatility drew criticism, and he was removed for cause in May 1944. His only child, a daughter, gave birth to Cornelius Crane, who became a comedian and changed his name to Chevy Chase. Browning retired as a captain in 1947 and died in 1954.

Stanhope Ring

went ashore with Pete Mitscher when Mitscher became Commander of Patrol Wing Two. His punctiliousness and loyalty continued to win him promotions, and as the war neared its end in May of 1945 he got command of the new escort carrier USS

Siboney

(CVE-112), though by the time that ship arrived in Pearl Harbor, the war had ended. Ring also briefly commanded the USS

Saratoga

, but only long enough to steer her to Bikini Atoll where, in July of 1946, she performed her last service as a target ship for an atomic bomb test. Ring proved to be an excellent peacetime officer, and won promotions to rear admiral and then vice admiral before he died in 1963.

Clarence Wade McClusky

was granted leave back to the States to recover from his multiple wounds and was replaced as CEAG by Max Leslie. He returned to active duty later in the war and commanded the escort carrier USS

Corregidor

(CVE-58). He also served in the Korean War and commanded the Glenview Naval Air Station near Chicago. He was promoted to rear admiral upon his retirement in 1956 and died in 1976.

Richard Best,

who put bombs into two enemy carriers on the same day, had the most curious postbattle experience of anyone. After landing his airplane following his successful strike on the

Hiryū

, Best began to feel queasy and started vomiting. He went to see the ship’s doctor and told him that during the morning flight, when he had first put on his oxygen mask, he had smelled “caustic soda.” He thought that might be the cause of the problem. Best became weaker by the minute and had to be carried back to his room on a stretcher. He could not hold down any food and lost weight dramatically. Eventually he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and by August he was in a Navy hospital, where he stayed for two years. Best never flew again, and he retired on full disability in 1944. The disease was not fatal, however, and he lived in Santa Monica, California, until 2001, when he died at the age of 91.

John S. “Jimmy” Thach

returned to the United States to formulate a new set of air tactics for the fleet. Afterward, he served as operations officer for Vice Admiral John S. McCain (grandfather of the Arizona senator) and ended the war as a captain. He commanded the escort carrier

Sicily

(CVE-118) during the Korean War and afterward the full-sized carrier

Franklin D. Roosevelt

(CV-42). He was promoted to rear admiral in 1955, to vice admiral in 1960, and ended his career as a four-star admiral in command of U.S. Naval Forces, Europe. He died in 1981 just short of his 76th birthday.

Joseph Rochefort

’s singular contributions to the American victory at Midway went unacknowledged for many years. The work of the codebreakers was necessarily secret. (After the battle, the Chicago

Tribune

ran a headline proclaiming: “NAVY HAD WORD OF JAP PLAN TO STRIKE AT SEA”; King wanted to arrest the publisher for treason.) But Rochefort’s work went unacknowledged officially as well. Though Nimitz recommended him for the Distinguished Service Medal, King, after consulting with John Redman, turned down the nomination, justifying his decision by saying that Rochefort had been simply doing his job and that it was unfair to single out any one person for work performed by a team of cryptanalysts. Of course, by that standard, no one would ever receive a medal. Rochefort was as prickly as King. When King reassigned him to duties unrelated to cryptanalysis, Rochefort refused the assignment. Despite that, he ended up in California, supervising the construction of a floating drydock in Tiburon. In the spring of 1944 he went to Washington to work under Joe Redmond, John’s brother and the director of Naval Communications. There, his job was to run the Pacific Strategic Intelligence Section, assessing Japan’s naval and military capabilities as part of the planning for an invasion of the home islands. He retired as a captain in 1953. Only when the role of the code breakers was declassified in the 1970s did Rochefort begin to get his due. He died in 1976, and, a decade later, he was posthumously awarded the President’s National Defense Service Medal.

Yamamoto Isoroku

tried to be philosophical about the outcome of the Battle of Midway. Whatever he may have felt privately, he accepted full responsibility for its outcome. He remained at the head of the Combined Fleet mainly because replacing him would require public disclosure of the defeat—news of which the government kept secret. But the defeat at Midway cost Yamamoto his leverage with the Naval General Staff, and in any case his options were severely limited by the crippling of the Kidō Butai. After the string of defeats in the Solomons in late 1942 and early 1943, Yamamoto decided to tour the front to bolster morale. His itinerary was transmitted in code to the various bases he was to visit, and the message was intercepted and decrypted by the code-breakers. The question of what to do with that information went all the way to the desk of President Roosevelt. FDR told Frank Knox that if they had a chance to get Yamamoto, they should do it. As a result, long-range Army Air Corps P-38 Lightning fighters intercepted him, and Yamamoto died when his plane was shot down on April 18, 1943. Yamamoto was 59.

Nagumo Chūichi,

who was not by nature a cheerful man, became positively morose after Midway. Yamamoto had promised him a second chance and kept his word, appointing Nagumo commander in chief of what was called the Third Fleet, which included both

Shokaku

and

Zuikaku

, now redesignated as CarDiv 1. In August he tangled with Fletcher again in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons (August 24–25, 1942). Though Nagumo’s pilots inflicted significant damage on the

Enterprise

, they failed to put Henderson Field out of action, and the Americans sank the small carrier

Ryūjō.

After another battle off the Santa Cruz Islands in October, which cost the Americans the

Hornet

, Nagumo retuned to Japan to command the naval bases at Sasebo and Kure. Then in March of 1944 (the same month that Mitscher got command of the Fast Carrier Task Force), Nagumo was charged with the defense of Saipan in the Marianas, which was about to be targeted by Spruance’s Fifth Fleet. By now the disparity of forces between the two sides was overwhelming, and Nagumo’s only prospect was to make the Americans pay a heavy price for their conquest. American Marines went ashore on Saipan on June 15, 1944, and quickly drove inland. The Japanese fought furiously, as they did everywhere in the Pacific, but they were soon forced back into a tiny enclave where they fought from a number of small caves. Two years before, Nagumo had commanded the most powerful naval striking force ever assembled, effectively the ruler of the vast Pacific Ocean. Now, at age 57 and suffering from arthritis, he sat in a cave as his world collapsed around him. In a dark recess of that cave, he put his pistol to his head and pulled the trigger.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Because most of my earlier work focused on the nineteenth century, I am more indebted than usual to the many people who offered assistance and advice in the preparation of this book. My first debt, as always, is to my wife, Marylou, best friend and life partner, and also a superb editor and patient sounding board. As usual, she was a full partner in the writing of this book.

Of the several World War II scholars who generously shared their time and expertise, my greatest debt is to John B. Lundstrom, Jonathan Parshall, and Ronald W. Russell, each of them careful and meticulous scholars of the Pacific War. As I was working on Midway, John Lundstrom was writing a history of the Ninth Minnesota Regiment in the Civil War. We worked out a mutually useful arrangement whereby we read each other’s manuscripts and offered suggestions and ideas. I am sure that I gained much more from this exchange than John did, and I am grateful to him for his help. Jon Parshall, coauthor of the excellent book

Shattered Sword

, which focuses on the Japanese side of the battle, read the second half of the book and generously offered suggestions and corrections. Ronald Russell, who manages the website for veterans and students of the Battle of Midway (

http://www.midway42.org

), read the entire manuscript and offered many corrections and suggestions. In addition, Bert Kinzey and Richard B. Frank each read sections of the manuscript and were generous in sharing their expertise. Vice Admiral Yoji Koda (Ret.), now at Harvard, and Lee Pennington at the Naval Academy helped me understand and appreciate the Japanese side of the story. Though all these scholars patiently tried to steer me away from error, it hardly needs to be said that any factual mistakes that remain, and all the interpretive conclusions, are mine alone.

At Oxford University Press, my excellent editor, Tim Bent, sought to limit my tendency toward the overly dramatic, Joellyn Ausanka steered the book through the production process, and Ben Sadock was a superb copy editor. Once again, I am in debt to this team of professionals at OUP.

Among the many librarians and archivists who guided me to resources, I want to thank Barbara (Bobbi) Posner, Curtis Utz, John Hughes, and John Greco of the Naval History and Heritage Command at the Washington Navy Yard. Thanks are due as well to Evelyn Cherpak at the Naval War College Archives, and to my longtime friend John Hattendorf as well as Doug Smith of the Naval War College faculty. Ginny Kilander welcomed me to the American Heritage Center on the campus of the University of Wyoming in Laramie; Bob Clark, Matt Hanson, and Mark Renovich provided assistance at the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, New York; and Elizabeth Navarro was my guide at the Hornbake Library at the University of Maryland. At the Naval Academy, Barbara Manvel and the Interlibrary Loan librarian, Flo Todd, helped me as always. In the Special Collections room, where I spent many days alternating between studying manuscripts and enjoying the beautiful view of the Severn River, I was assisted by the archivist Jennifer Bryan as well as David D’Onofrio and Dorothea (Dot) Abbot. Jeffrey Ward created the thirteen maps in the book, and Janis Jorgensen at the U.S. Naval Institute assisted me in finding the illustrations, as did Robert Hanshew at the Naval Historical Foundation Photo Archives. My friend Tom Cutler helped me with details about naval procedures.

I also want to thank several people who helped me simply because of their love of the Battle of Midway. These include Phil Hone, Alvin Kernan, Bill Price, and Peter Newberg. I particularly appreciate the interest and assistance of many Midway veterans who offered their help, especially John “Jack” Crawford, Norman “Dusty” Kleiss, Donald “Mac” Showers, and Bill Houser.

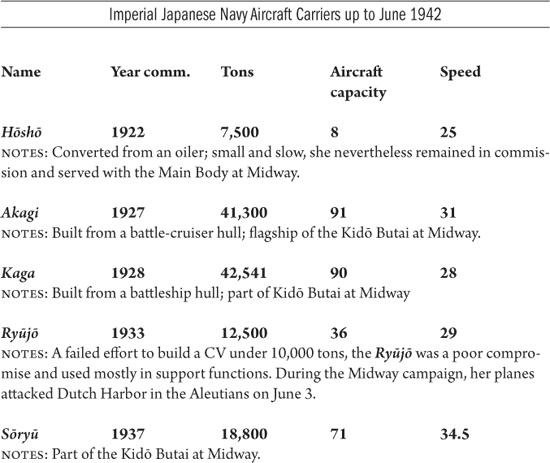

APPENDIX A

American and Japanese Aircraft Carriers

(NOTE: USS

Essex

, the first of an eventual twenty-four carriers of her class that would be built during the war, was launched in July 1942 and commissioned in December. She and each of her sister ships displaced 36,000 tons and carried 90–100 aircraft.)