The Candy Smash (4 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Davies

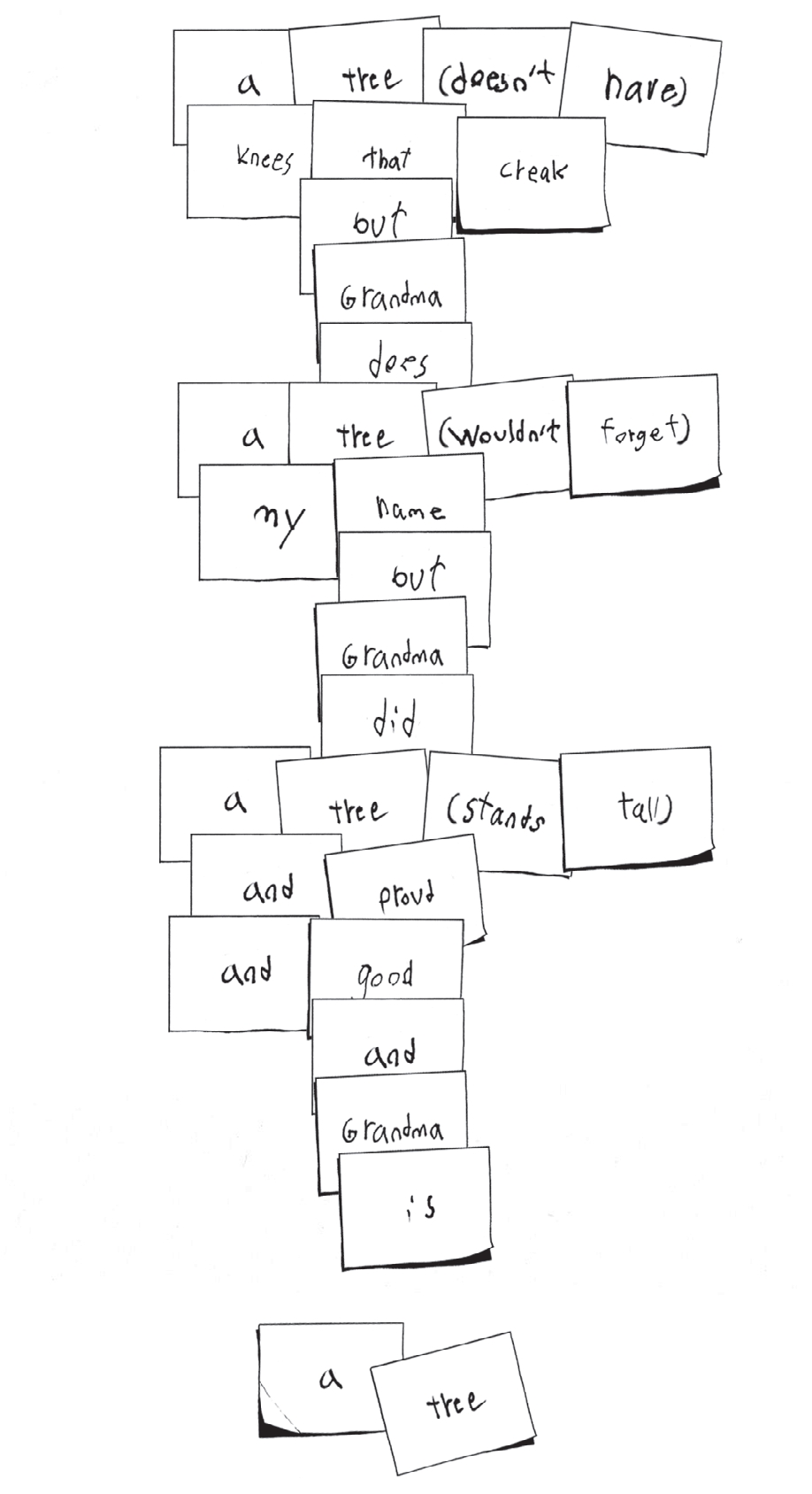

After half an hour, he stared at the Post-it notes on his desk, then decided to add some parentheses, just like E. E. Cummings.

Evan read the words out loud and thought,

That's a poem.

But was it a love poem? That was the assignment that was due on Friday. Love poems for pets or people or frogs or sunshine or anything else in the world that could be loved. Mrs. Overton had read a love poem to them by Langston Hughes, the poet she had named her cat after. It was a poem about rain, and the last line was "And I love the rain."

Evan wasn't so sure if his poem about his grandmother counted. Didn't a love poem have to say the word "love" somewhere in it?

Then he thought about E. E. Cummings and how all his poems shouted out,

There are no rules!

and Evan decided that he liked his poem just the way it was, and if you couldn't tell that he loved his grandma, there was something wrong with you.

Suddenly he heard voices in the hallwayâJessie's and someone else'sâand then laughter. Evan froze. He knew that laugh. He was in love with that laugh.

Primary Source

primary source

(n) a person with firsthand knowledge of an event; a document written by such a person at the time the event took place

Â

Jessie paused in the school hallway, twisting the strap on her backpack back and forth. She knew the rule. Kids were not allowed in the classroom after school when the teacher wasn't there.

The door was open. She poked her head into 4-O. No one was there. The chairs were all up on the desks. The shades were pulled down for the day. Even the gerbils were in silent hiding, nestled deep beneath the wooden shavings in their cage.

Jessie tiptoed in. Her heart was beating wildly in her chest, and her breathing felt short and choppy. Her heavy backpack pulled on her arms as if trying to hold her back.

She approached Mrs. Overton's desk, which was near the window. On top, there were several neat piles of papers, her pen-and-pencil cup, a shallow dish full of paper clips, two photographs of Langston, and a wilted African violet. Jessie reached out and quickly rubbed one of the plant's leaves between her thumb and fingers, enjoying the velvety feel of the little hairs that covered the leaf. The soft touch of the plant calmed her down. But she didn't have much time. Megan was coming over to her house in half an hour to make their class valentines. And anyone could walk into the classroom at any moment. She would have to be fast. A real pro.

Jessie's eyes scanned the desktop, looking for clues, but what was she looking for? Nothing seemed unusual. Nothing that would reveal Mrs. Overton as the secret person who was leaving candy hearts.

She walked around the desk and took a quick peek in the trash can, spotting only an empty paper cup and an orange peel.

Out in the hall, a locker banged shut with a sharp metallic

clang!

Jessie could hear the sound of a squeaky cart rolling down the hall. She stopped. What if Mrs. Overton came back? Her coat was still hanging on the hook; her purse was underneath the desk. What if the custodian came in to sweep the floor? Would Jessie be expelled from fourth grade?

But she had to be brave. Her newspaper was due in less than a week, and she didn't have a front-page story. There was a secret in 4-O, and it was her job to uncover the truth.

She looked at Mrs. Overton's desk. There was one long, thin drawer in the center and three deep drawers on each side. Jessie wondered whether the drawers were locked. She wondered which drawer was most likely to hold a secret.

Her heart started to beat faster. Her dad did this kind of thing all the time, right? When he told his storiesâof classified documents and uncovered clues and secret meetings with sourcesâhe never mentioned being nervous.

She reached her hand toward the top desk drawer.

"What are you doing?"

Jessie's hand jumped back as if bitten by a snake and disappeared behind her back. David Kirkorian stood in the doorway, buried inside his winter coat, woolen hat, and bulky gloves.

"Nothing!" said Jessie. "I forgot my social studies notebook!" This was the excuse she had planned ahead of time, and she had in fact "accidentally" left her notebook in her desk.

"So why are you looking in Mrs. Overton's desk?" David walked up to her and pulled off his hat. "She doesn't keep our notebooks in her desk."

"Why are you even here?" asked Jessie. Was David going to report her to the principal?

"I saw you walk back into the school, and I thought maybe you needed help with something." He took off his gloves and stuck them under his arm. It was warm in the classroom, and his face was beginning to turn bright red with the heat.

"I don't need help," said Jessie. And she didn't. At least not from David Kirkorian, of all people!

He looked at her, then at the wall, then back at her. "I won't tell, Jessie," he whispered. "I'll keep your secret."

"There is no secret!" shouted Jessie. She hurried past him, grabbed her social studies notebook from her desk, and ran out of the room.

Â

When Megan came over to her house, Jessie still felt jumpy. And she still didn't know what her frontpage story would be.

"Do you think I can just say that it's Mrs. Overton who's giving out the candy, since it obviously is?" asked Jessie. She and Megan were in the basement, making their cards. Valentine's Day was just five days away, and Jessie was worried about getting all twenty-six valentines done in time. Another deadline! There was so much pressure in fourth grade!

"Isn't that against the law?" asked Megan. "I mean, if it turns out not to be true?" Megan had the messy idea of filling her envelopes with confetti, so she was busy cutting up tissue paper.

"Yeah," said Jessie glumly. It was called

libel,

and you could go to jail for it. "But who else could it be?" Jessie was decorating the edges of her heartshaped valentines with little glue-on jewels, following a strict patternâred, silver, purple, silver.

"You never know!" said Megan, and she tossed a handful of confetti into the air so that it rained down on the table.

Jessie brushed the confetti off her side, glad that it hadn't landed in any glue. "Well, if I can't write about the candy hearts, what am I supposed to write about on the front page of my newspaper?"

"You should write about how we're not allowed to include

any

candy in our class valentines this year," Megan said. It was a new rule, and all the kids were against it. She reached for a sheet of pink construction paper and started to cut out a heart. "It's un-American!" Megan's uncle owned a candy factory, so Jessie could understand why she'd be upset.

"That's not a very interesting story," said Jessie. Sure, everyone in 4-O was mad about the new rule, but there was nothing to

investigate.

Candy was bad for your teeth, and grownups cared more about healthy teeth than they did about a kid's happiness. End of story.

"Then we should

make

a story!" said Megan. "We should have a protest. Sign a petition. No! A sit-down strike! We should all refuse to do our homework until that rule is changed!"

Not do homework? Jessie stared at Megan. That sounded completely crazy to her.

"Bad idea," she said. "I need to uncover a

secret

."

Megan stopped cutting her paper and looked at Jessie. "That doesn't sound very nice. If someone has a secret, they probably don't want you printing it all over the front page of a newspaper."

"Secrets are bad," Jessie said, thinking of the big chemical company and the lying senator. Clearly Megan didn't understand what investigative reporting was all about.

"Some secrets are nice," said Megan, smiling.

There was a clomping sound overhead, and then the door to the basement squeaked open. "Hey, Jess, it's almost dinner," said Evan, but instead of closing the door and going back upstairs, he continued down the steps and wandered over to the table where they were working. "My mom says you can stay, if you want to," said Evan, not even looking at Megan. "What's that?" he asked, pointing to the pile of shredded tissue paper.

Megan grabbed two fistfuls of the confetti and held them up to her head. "It's my new hairdo! Do you like it?"

Evan burst out laughing. Then he grabbed a fistful and held the confetti paper up to his chin. "Do you like my beard?" he asked in a deep voice, and Megan practically fell off her chair, she laughed so hard. Jessie really didn't get what was so funny.

"You guys are weird," she said, bending over her valentine and pressing the last jewel into place. But she wasn't listening to them anymore. She was thinking about the secret in Mrs. Overton's desk drawer.

Â

The next morning an even bigger secret appeared. It popped up inâof all placesâthe girls' bathroom.

To Jessie, the girls' bathroom was a scary place. Things happened in the bathroom, things that teachers never knew about. Words were whispered, graffiti written, rules broken, trash dumped, water left running, hands left unwashed, noses picked, bodies shoved, names calledâanything could happen in the bathroom, because there were no teachers watching. Ever. Jessie had never once seen a teacher enter the girls' bathroom.

For the most part, Jessie avoided the bathroom. She took care of her business at home and, when necessary, in the private bathroom in the nurse's office. But this year, Mrs. Graham had started to "encourage" her to use the girls' bathroom in the hall. At first, Jessie had politely declined, but after a few weeks, it stopped being an offer, and Jessie had to "adapt and evolve," as her mother would say, to this new way of doing things.

Jessie pushed open the old, scarred wooden door of the bathroom and stuck her head in. She didn't mind the bathroom when it was empty, and she didn't mind it when it was jam-packed. But if there were just a few girls in thereâespecially any of the mean girls from her class last year or the scary big fifth-graders who looked like they were practically teenagersâshe would duck back out and look at the artwork in the hallway until the bathroom emptied out.

This morning, the bathroom

was

empty. Jessie hurried to the only stall she ever used, the second-to-last one in the row, and quickly sat down to pee. She liked this stall because the lock worked and because most kids never used it. She had observed this: kids either liked the first two stalls closest to the door or the large, handicapped stall that was like having a room all to yourself. But no one ever chose the second-to-last stall, and that's why Jessie decided it was the safest one of all.

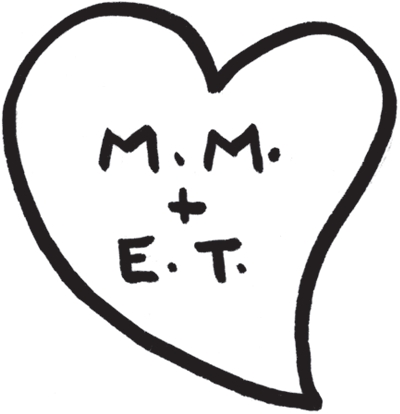

Today, when she sat down, she noticed something new, right in front of her face, written on the door in black ink.

Â

Â

The first thing she thought was that Megan's initials were M.M., but she could tell that Megan hadn't written the letters because Megan always drew curlicues at the ends of her

Ms,

and these

Ms

were straight up and down.

The second thing she thought was that

E

and

T

were Evan's initials.

Of course, it was a big school with a lot of kids, and all the grades used this bathroom. Maybe

M.M.

and

E.T.

were fifth-graders. That made more sense. Older kids did bad things, like writing on bathroom doors.

When Jessie finished, she left the stall to wash her hands. And then she forgot all about the initials because back in the classroom they were creating models of working lungs using soda bottles and balloons, and Jessie loved making stuff like that.

But later in the morning, when Megan twisted around in her seat to talk to Tessa while Mrs. Overton was giving a math lesson on decimals, Mrs. Overton said, "Megan Moriarity, eyes up front, please!" And Jessie thought again about those initials and what they might mean.

It was like a math equation with symbols:

Â

if

Â

M.M. = Megan Moriarty

Â

and

Â

E.T. = Evan Treski