The Crystal City Under the Sea (19 page)

“One day my father said to me: ‘Atlantis, the look of care I see in thy pale brow, thy hollow cheek, thy haggard eye, has entered into my heart.’

“‘Father,’ replied I, ‘ forgive a weak girl. I cannot help it. Yes, I confess that black care has taken possession of my soul. This cruel imprisonment weighs me down.’

“ ‘And thou hast not confided thy trouble to thy father?’

“ ‘Respect, and the fear of displeasing thee, have kept my mouth closed.’

“ ‘Speak! I authorize thee to do so.’ Then I told him, not so freely, perhaps, as I am telling you now, for I feared that he might imply that I reproached him, how much I longed for change, the great desire I felt to see the land of the living, my true country; to escape, if only for a short time, from this tomb which was crushing my heart. Charicles did not say much in response to my confession; when he spoke, they were oracles which fell from his lips, and, if he had had a word of blame for my aspirations, there would have been no appeal against it. But he was doubtless touched by my distress, though neither a word nor a look betrayed it to me then. For I soon found that he was making preparations for a voyage. My father is a good workman as well as a clever mechanician. With his own hands, he constructed a shallop hermetically closed, attached to a floating air-balloon fitted with hydrogen gas, by which we could rise to the surface of the water. It was a marvel of lightness and elegance.”

“Ah!” cried René, “how much I should like to see it!”

“I should think you would, indeed,” said Atlantis, smiling; “ there is no need for me to boast to you about a prodigy such. as you have accomplished yourself in an inverse sense, that is the only difference. But alas, thou wilt never see it, this vessel which was so dear to me, for Charicles destroyed it with his own hands!”

“Heavens! did the noble artist become a prey to temporary madness?”

“No,” replied Atlantis, shaking her head, “the dark furies never clouded the clear understanding of Charicles; it was by a deliberate act that he reduced to nothing the work of his genius. This is what happened: Everything was in readiness for the ascent I had been longing for. Trembling with impatience, I waited for my father to give the word for me to set foot on the boat, when he took my hand and said to me, with great solemnity:

“Atlantis, the object which thou hast so much desired is about to be accomplished. Before thou seest the region which attracts thy curiosity, it is my duty, it is due to our traditions, to warn you of three things: our excursion must be bounded by the liquid element; neither Charicles nor Atlantis must ever land upon the shores of continents inhabited by barbarians. In the second place, we must avoid attracting attention from any vessels we might meet, and lastly, and this point I insist upon, these excursions must be of rare occurrence and very short, and, if I find that thy heart is too much set upon them, and that thou sighest after a different mode of life from that of thy fathers, I shall not hesitate to break in pieces the instrument which will have helped thee to be unfaithful to thy own home!”

“I promised all my father wished. I thought that I could bend to his will, and I was, moreover, so happy at the thought of going that I hardly paid attention to what he said.

“The boat leapt from the point from which he detached it with prodigious speed, and, in a few moments, we were at the surface. What a spectacle! Phoebus, having almost finished his course, was about to plunge with his flaming car below the wide expanse. Already a star had appeared. A little later the sun disappeared; other stars shone out; a balmy, divine breeze fanned our faces. Ye gods, what wonders! How could any one enjoy such pleasures day by day and call himself unhappy? My father pointed out the constellations to me, and showed me how to set a quadrant. I listened to him as in a dream; he seemed to me to be numbered among the gods. But soon a sharp pain smote me to the heart, when he said: ‘Prepare to descend again.’ I was on the point of letting entreaty, a word of remonstrance, escape me, but I stopped in time. For the first time in my life I dissimulated. With a force that I cannot explain to myself, I controlled my face, called up a laughing expression, and accepted with apparent indifference the signal to return. I felt that I must at any cost see these splendid heavens again, feel the rocking of the waves, drink another deep draught of the blessed air. I learnt how to wait without betraying my haste till my father decreed another excursion into the upper world, but I was devoured with impatience. At last, the moment so long waited for arrived; my father, much pleased with me, gave me the reward of my obedience. And so we repeated the pleasure several times, and I lived only for them.

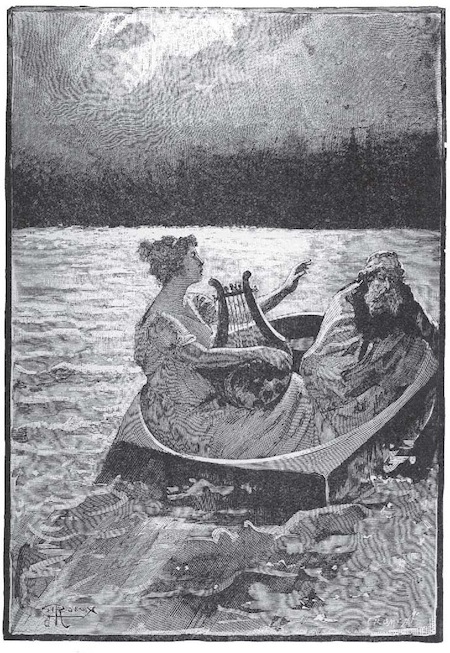

“One night, not very long ago, we were floating, impelled by a light breeze, when a vessel of elegant proportions appeared in sight. By degrees it came nearer; I felt sure I saw a human form on the deck! Ah! young stranger, thou canst form no conception of the emotions that passed -through my mind! My father was absorbed, or sleeping, I do not know which. He did not appear to pay any attention to what was passing around him. Suddenly the god of harmony took possession of me, involuntarily, and almost without knowing what I did, I gave utterance to the feeling that oppressed me, and a song escaped my lips. My father had carefully trained me

The song of Atlantis.

in the art of music, but this song I had never learnt. It had a sad, irresistible, spontaneous expression, the aspiration of my soul. I ceased, consoled at having given a shape to my anguish; but imagine how my heart fluttered at the sound, at a little distance, of a musical voice raised in its turn across the water. It seemed as if the sea had brought a response to my call. I could not understand the words, but I remember the melody. I shall never forget it as long as I live.”

“Atlantis! Atlantis!” cried René, who for some moments had scarcely succeeded in controlling his agitation, “I am certain I know that melody, let me repeat the words to you.” And, in a voice in which deep feeling could not conceal the purity and fulness, he repeated the first few words of Marcello’s hymn:

“The heavens are telling.” Atlantis, with dilated eyes, seemed petrified with astonishment; but soon, two tears, the first he had seen in her eyes, betrayed her tender joy.

“It was thou! it was thou!” she articulated, in a stifled voice.

“ Yes, it was I, and it was thou!” repeated René, not less moved, not less happy. “Ah, dear Atlantis, here is a link worth ten years of friendship. It was while I was sounding from the yacht Cinderella. It was midnight; I was alone on deck when I heard a divine voice piercing the pure air. How many times I have ineffectually tried to transcribe those incomparable stanzas!”

“I could not repeat them again myself,” said Atlantis. “All that I know is that they came straight from my heart, and also that they shut me out forever from the upper world, for, at the sound of my voice, Charicles suddenly awoke from his reverie. ‘Miserable girl!’ cried he, ‘what hast thou done? Like the deceitful sirens, dost thou use a gift from heaven to enchant thy own father, to lull his watchfulness over thee to sleep? Hast thou forgotten thy vows? Say farewell to the starry vault, to the waving waters, to the seductive air. Thou shalt never see them again.’ The sides of the boat closed over us and we sank under water. A fragment of thy song still rang in my ravished ear. The next day Charicles destroyed his chef-d’œuvre. No words can paint my grief to thee. I lost all hope.”

CHAPTER XVII

CHARICLES IMBIBES SOME MODERN IDEAS.

D

EEPLY moved by what they had just discovered, and occupied with again and again going over the recollection of that strange meeting, and corroborating the details of it by their simultaneous proofs, marvelling at the prodigy, saying to each other over and over again that it was a unique occurrence, and an evident indication of destiny, the two young people were unaware that Charicles, for a long time, had lain with his eyes open.

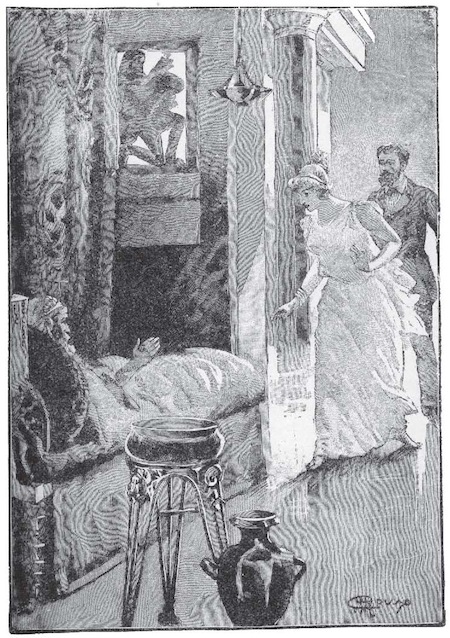

“Attention!” the old man suddenly articulated. Overjoyed, they flew to his side. What new miracle was about to be accomplished? The invalid’s voice was quite clear, his eye bright, and his features had lost their rigidity; but what struck them still more than these welcome signs of a return to life, was the new expression on his face. Neither of them could have explained how it was, but he seemed to them to have become a new man, previously unknown to them. In this spirit, devoted unswervingly to appearances, to the exclusive worship of the past, the present came as a revelation, and pity had penetrated his inexorable heart.

“My children,” said he, “I want to speak to you. While you have been talking, I have heard you, I have been listening, I have understood. More than once I have tried to raise my voice to speak to you, but I could not; my tongue was tied. It was fated that I should wait and hear you to the end, that the scales might gradually fall from my eyes, that my obstinate heart might learn the lesson taught by this young stranger, of humanity and pity. Atlantis, it is not seeming that an old man should humble himself before the young, much less a father before his child. But I wish, before going to join

The recovery of Charicles.

the shades of my ancestors, to confess that I have been hard towards thee. I believed I was acting rightly; I was prompted by tradition.”

“Father, revered father,” said the trembling girl, throwing herself on her knees beside the bed, and pressing his wasted hand to her lips, “do not speak thus. Forgive my audacity. Thou alone knowest what thou oughtest to say. But I cannot bear to hear thee reproach thyself on my account,—thou so noble and so great! No, I cannot. Thy words are like a sword piercing my heart. I was wrong to complain, seeing that all my destiny has been ruled by wisdom itself. Forget, father, the imprudent words, which a hostile power doubtless dictated. I call the gods to witness, the gods that have always protected our family, that my respect for thee and my gratitude to thee will never fail.”

Sobs choked her voice, and prevented her from continuing.

“Calm thyself, my daughter,” said Charicles, stroking her fair head fondly. “Thy readiness to accuse thyself is a proof of thy generous heart. If thou hast wronged me it is but a light matter, and I forgive thee; but I must speak, and thou must listen to what I have to say. I have heard it said,” continued he, dreamily, “ that wisdom sometimes issues from the mouths of children. It is true. I, an old man, versed in science, ripened by meditation, enlightened by history, and strong in experience, have learnt something from thy young lips; thou hast brought me a message. I have learnt that wisdom has clothed herself in a new form, and I acknowledge a power more beautiful than all I ever valued before; that virtue, that sentiment that thou describes!, young man, by the sublime words of brotherly love and pity between man and man. I believed that my science, being of more ancient origin, if not greater than all that thou hast attained to by groping in the dark, justified me in keeping up a haughty reserve, refusing to have anything to do with barbarians, as our Greek fathers called all those who were not of their race, in affirming to the end our essential superiority. It is right that I should stoop to own that the world has progressed without us. I believed that, having reached the highest point of perfection, we ought to remain stationary for fear of deteriorating; but thou hast shown me to what error my pride led me. Not that thou hast ever made use of arrogant or exaggerated words to boast of the great things accomplished by thy race. Modesty reigns on thy lips, and I am pleased by the importance thou givest to the sentiment to which thou givest a new name, that of patriotism. Far from seeking to dazzle me with a picture of civilization acquired without effort, thou hast described to me the painstaking work of centuries, the slow conquests of heredity, and the laborious progress of moral ideas. I understand now what we have missed. I see, at my life’s close, that during the whole of it I have hugged a phantom in my arms, a withered skeleton. Of what use is a science which will not be beneficial to others? What good is there in riches, beauty, power if not shared with humanity? But the error that could only affect me was nothing to the much graver wrong of condemning my daughter to a destiny which could only be heavy and cruel!