The Diary of Ma Yan (12 page)

Read The Diary of Ma Yan Online

Authors: Ma Yan

I'm always full of suffering and worries. No sooner do I lower my head than Mother's words come into my mind, together with her ravaged hands. Why does this word

mother

leap into my mind so very often?

I like the politics teacher's way of using words as well as his manner. But I don't like the subject he teaches us. All we ever do is discuss heroes of history, patriotism, Taiwan, and morality. In each of his classes I secretly do my homework for other subjects. The teacher often says we should listen carefully. But I can't seem to correct my bad habits.

Today when we had a lesson with him, he picked me out, asked me to stand up. He wondered if I could answer a question. I shook my head. He let me sit down again. I know what he wanted to ask me: Could I listen more carefully during his class? That's why I refused to answer.

He shows me a lot of consideration, and I always disappoint him. From now on, I'm going to change my habits. I don't want to let him down anymore, or make him unhappy.

Monday, November 19

A fine day

At noon after classes the comrades go home to eat. Since I'm a Hui, this is a fasting period for me. I've started Ramadan. This gives me a little free time.

In the street where I walk, I feel terribly alone. I think of Mother again. If only she were hereâ¦how wonderful that would be! Because everything I do is in relation to her.

If I make some kind of mistake, and haven't checked with her for her advice first, she chides me all day. Sometimes I resent her. But when I think about it, I know that she's doing it all for my own good. I mustn't get angry with her. If I hadn't followed her advice, where would I be today? I would lack maturity and I would understand nothing of the good things in life. If I hadn't had Mother teaching me, with all her criticisms, I wouldn't know what a fen or a yuan was, nor where they came from.

Without Mother, there would be no Ma Yan. I must be grateful to the woman who allowed her daughter to grow, to mature, and to become herself.

Thursday, November 22

A fine day

This week has flown by. It's already Thursday, and I don't know how we got here. I have a great wish to go home.

There's news in the village. We're putting in place measures that will allow the fields to be planted with trees. Each week when

I go home, the village has changed a little. The hills have acquired holes at regular intervals. In the spring we'll plant the trees. All of us will be really excited. Our land will turn green again.

I think that in a few years, or maybe a few decades, the landscape will have changed completely. These days, everywhere you look, there's only yellow earth. If you walk up to the high plateau to look down at the village, all you can see is yellow barrenness, a dried-out terrain. It's not even a landscape. To tell the truth, there's nothing to see.

Nor does the economy produce anything. Only

fa cai

allows one to live at all. The situation has to change. In the future, our village will be green. Its inhabitants will have acquired knowledge and will know how to build solid houses. If I work hard at school, when I grow up, I'll be able to devote my energy and skills to improving the cruel life of the villagers.

Wednesday, November 28

A bright day

This evening after classes a friend invited me home. She's like the little sister I would have liked to adopt. Her family lives fairly close to the school. There's only one valley to cross. On the way we meet several comrades who look happy. Seeing their joy, I too would like to be home. They all say how wonderful it is to sleep in one's own home.

At first when I get to my friend's house, I feel ill at ease. But her parents are very nice and ask me lots of questions. When we got there, her father came out onto the porch to welcome us. At

my place when we have guests, it's my mother who welcomes them. Father stands near her, because he's not very savvy about dealing with people.

No sooner had we come in than my friend's parents brought us two bowls of meat. The steam was still rising from them. Then came fruit.

I envy my friend having a family that's so hospitable and happy. She doesn't have to worry about them. And they eat meat! I don't know how long it's been since we ate rice with meat at home. At the next market, I'd love to buy a little meat for Mother.

Tuesday, December 4

Light snow

Snow is floating in the air. I miss my village. We're in the midst of a history lesson, and the teacher goes on and on. I'm sitting near the window. When I turn my head, I can see snowflakes fluttering through the air before drifting to the ground. It takes me back to my childhood.

It was a very cold winter morning. Snow was falling thickly. My parents weren't home. They had gone far away to harvest

fa cai

.

My mother's illness started that winter. It was a hard and bitterly cold one. The snow rose high all around us, more snow than I had ever seen since I could remember. When the snow and wind stopped, my brothers, my grandmother (who was about seventy then), and I filled our underground tank with snow so that there would be no shortage of water during the winter.

Every Saturday when I'm at home, Mother asks me to collect up the donkey droppings. And I never manage it. She reminds me then of that snowbound winter. She says, “You were so little, but so brave. Now you've become weak and useless. What shall I do with you?”

Every time Mother talks like that, I remember the cold of that winter. I don't know how Mother and Father survived it. I don't know how I managed to carry all those bundles of snow. I don't really recall much except the cold and the snow. I only hope that I'm braver now than I was then.

Friday, December 7

A gray day

The fair is on today. My heart light, classes seemed to race past much more quickly than usual. I floated to the market, carried by one great hope. Last Saturday Mother promised she'd be there today. Since Ramadan is almost over, she has to come to the market to buy presents for people and invite an aged person home to break the fast.

The wind whistles, and it's so cold that you can't take your hands out of your pockets. As I walk through the streets I see all kinds of people shivering with cold. I look for Mother but I can't find her. The tears start to run down my face. They freeze into ice. I meet a lot of women wearing a white kerchief just like Mother's. I'm tempted to stop one of them, take her hand, call her “Mother”â¦but as soon as I step forward, I see that she isn't my mother and I stop myself.

I have the feeling someone is calling me. I turn around and see Father. My heart is suddenly less empty. But he isn't Mother. My father comes up to me, mutters a few words, and heads off. When it's Mother, she launches a barrage of questions at me. I love that. It's so engaging. And then it's so difficult to leave her.

Why do I spend so much time thinking about Mother?

Thursday, December 13

A fine day

It's market day again today. I'm very happy. I'm sure Mother will go and break the Ramadan fast with her maternal grandmother. But at the market, when I look for her, I can't find her. She hasn't come. The tears pour down my face. What a disappointment. Every market day I come in the hope of seeing her, and she isn't hereâ¦.

I'm walking with my head down when I see my maternal grandfather and my father. They're talking enthusiastically. But they're dressed in rags. Their clothes are dirty, their shoes full of holes. They look so ugly to me! On top of it all, they've got napkins around their waists, which makes them look even worse.

I don't know what my grandfather has eaten on this holy day, but as his granddaughter, I should be performing a pious act on his behalf. So I buy him fifty fen worth of apples, so that he can celebrate the end of the fast with them. But he disappears before I can give him his present.

At the vegetable market I meet my maternal grandmother. My grandfather asked her to buy some apples, she tells me. So I

give her the apples I bought, and on top of it, go and buy pears for her. I've spent a great deal of money in very little time. It's not that I wanted to, but I couldn't do otherwise.

I turn back toward school. In front of the market entrance I see an old woman who reminds me of my paternal grandmother. I buy fifty fen of pears. She too looks over seventy; she's arrived at the age where one must have feelings of respect toward her.

I've used up all the money I intended to spend on a notebook. Apart from the thirty-five yuan I spent in the district capital when I went to take the entrance exams, this is the first time since elementary school that I've spent so much money all at once. Two yuan! But I had to. To honor a great feast day you have to buy good things to eat, beautiful clothes for the whole family. I have little enough apart from my sense of responsibility and the piety that lives in my heart.

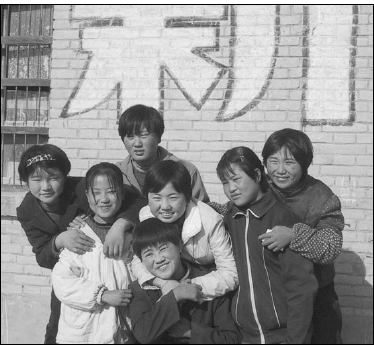

Ma Yan with the first six schoolchildren funded by the readers of the newspaper

Libération

When the French newspaper

Libération

printed an extract from Ma Yan's diary in January 2002, readers responded in great numbers. They were touched by the fate of this Chinese girl, moved by her rebellion and her desperate desire to continue her schooling. Readers proposed financial help; some offered to finance her education, however long it took.

In response to this outpouring, we created a fund called the Association for the Children of Ningxia in the summer of 2002. This fund would help the children of families in need to continue their schooling. There was no question of creating a vast organization; we just wanted a simple system for sponsoring children. The only condition of the sponsorship was that the children wrote to us once a term to give us news of their studies and tell us how things were progressing.

After the publication of the article about Ma Yan, first twenty and then thirty children benefited from European sponsorship. This is a drop of water in an ocean of need, but it makes all the difference to these children. All of them wrote to us to say that school was going well.

The spontaneous gesture of Ma Yan's mother when she put the notebooks into our hands, a little like the way one tosses a message in a bottle to the high seas in desperate times, has had consequences far greater than she could have imagined. Her life, the life of her family, and the lives of many other children in this forgotten village at the end of the world have been transformed.

Dear Uncles and Aunts,

*

Â

How are you?

**

I received your letter on February 17, 2002. That day my father had gone to town for the market and he found the letter at the post office. He opened it right away, but there were a few characters he couldn't recognize. Back at home, he asked me to read it. When I had finished reading, I don't know why, but I broke out in a sweat, as if all my strength had goneâ¦. Maybe it was because I was just too movedâtoo, too happy.

Father said, when he had finished reading the letter, that he no longer knew if he was walking on earth or in the sky, because he felt as if his body was floating. Mother added, “Finally, the heavens have opened their eyes. I didn't cry for no reason while I was up in the mountains. My tears then were the result of pain and sadness. Now they come from joy. I wish you a very good year and convey all my gratitude.”

After reading your letter, I really understood what joy in this world means: friendship and the meaning of life. I thank all the people who have set out to help me. I am thrilled that young French people want to be my friends. I would like to write to them, phone them immediately, but I have neither their addresses nor phone numbers. Then too, they don't speak Chinese. I hope that you'll give them my address; I would like to be their friend, their best friend. I say “Thank you”

*

to all of them.

You said that you could help other children from families in need. I'm so very, very pleased about that. For me, my problems are now behind me. Let them, too, complete their schooling and fulfill their dreams. All my thanks.

Soon I'm going back to school. I will work very hard not to disappoint all your expectations.

I wish you great success in this Year of the Horse.

Ma Yan

February 19, 2002