The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice (27 page)

Authors: Patricia Bell-Scott

Tags: #Political, #Lgbt, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #20th Century

In addition to this, I think that there will be a time which will come very soon after the war…, for those of us who really care that this question…be settled without bloodshed,…will have to stand up and be counted and that will be the time when to make such a statement would have some effect and some meaning.

I believe, of course, that all public places should be open to all citizens of the United States, based entirely on behavior and ability to pay as individuals. I do not think this has anything to do with social equality which is concerned with one’s personal relationships. I might be quite willing to sit next to someone in a streetcar or a bus whom I would not want in my own house but that person would have just as much right in the streetcar as I had and we should be judged entirely on our behavior. But any statements such as I am making in this letter will be much more effective when no campaign is going on and should only be made after we get our four basic rights accepted, unless the situation becomes such that in order to help people to be patient we have to give them the feeling that there are people with them who will help them, which may save us from bloodshed.

This letter is confidential and not for publication and that is said because of the way in which people have been publishing all I have written lately!

Very sincerely,

Eleanor Roosevelt

· · ·

BECAUSE MURRAY WOULD BE IN

Los Angeles until October 1, she had not yet made contact with ER’s friend

Flora Rose. Eager for the two to meet, the first lady shared an excerpt of a note she’d received from Rose. “

Your young friend Pauli Murray has not gotten in touch with me as yet but if she does I shall be so glad to see her and talk with her,” Rose had written. “There is so much which intelligent and educated colored people have ahead of them to do for their people at this time. Furthermore, there is so much the colored people are doing with their increased opportunities which are against their own interests it makes me heartsick at times.”

Murray promised to call on Rose, but Rose’s language made Murray bristle. “

It does worry me when people talk of ‘my people’ or ‘their people,’ ” she explained to ER. “If we start thinking about Americans it helps to dissolve some of the superficial differences. I find so many well intentioned ‘white’ people using that phrase, and it always irritates me. Forgive me, I know your friend means nothing by it, but if you feel as I do, I wish you’d convey the idea to somebody about it.”

In her youth, ER might not have understood Murray’s feelings. Now, thanks to a diverse network of friends and associates, the first lady’s consciousness had been raised. “

You are right we should think about Americans,” she responded. “I think both Miss Rose and I do. It is curious how thoughtlessly we use words.”

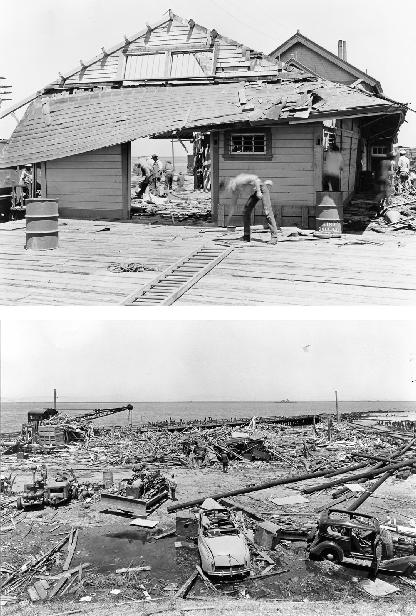

The railway station (above) and the pier (below) at Port Chicago naval munitions base, in California, were destroyed by an explosion in July 1944. Like Thurgood Marshall, Pauli Murray held the navy’s “policy of discrimination and Jim Crow directly responsible for this incident.”

(U.S. Naval Research Center)

24

“The Whole Thing Has Left Me Very Disturbed”

I

n October 1944, Pauli Murray covered the

court-martial of fifty African American seamen on

Yerba Buena Island, in San Francisco Bay, for the

Los Angeles Sentinel

.

The Port Chicago Fifty, as the group came to be known, were charged with conspiracy and mutiny for refusing to load ammunition after a cataclysmic explosion at the Port Chicago Naval

Magazine. Of the 230 navy personnel and civilians who died, 88 percent were black. This disaster accounted for 15 percent of all the deaths suffered by black military personnel in World War II. The court-martial of the Port Chicago Fifty was the first “

mass trial” of the war.

Located on the Sacramento River thirty miles northeast of San Francisco, Port Chicago was built shortly after the United States declared war on

Japan. The weapons loaded at this installation were indispensable to the war in the Pacific. The demand for munitions was so great that Port Chicago operated around the clock in eight-hour shifts. Approximately 125 seamen worked each shift.

The navy had accepted African Americans, albeit reluctantly, “

for general service” in 1942. Secretary of the Navy

W. Frank Knox and Secretary of War

Henry L. Stimson were opposed to integrating the armed forces. Thus, blacks lived and trained in segregated facilities and were assigned to labor battalions or as stewards. Even after Doris “

Dorie”

Miller, a twenty-two-year-old black messman from Waco, Texas, pulled the wounded captain of the

USS

West Virginia

from the line of fire during the attack at

Pearl Harbor and downed several Japanese planes using a machine gun for which he was not allowed to be trained, the navy refused to place blacks in combat or supervisory positions.

Of the fourteen hundred black seamen stationed at Port Chicago, not one, Murray discovered, was a commissioned officer. Yet all of the seamen loading munitions ships were African American. The danger and difficulty of their assignment; the lack of opportunity for advancement, transfer, or recreation; and racial hostility on the base and in the adjacent town fostered resentment and low morale.

Neither the seamen nor the white officers who supervised them had been trained to handle explosives. The loading process was harrowing. After the munitions arrived at the pier in railroad boxcars, the men broke the containers open with crowbars and sledgehammers. They then rolled, lifted, or passed the matériel to ships, where it was stacked in layers. Some bombs weighed as much as two thousand pounds. The pressure to load the weapons as quickly as possible increased the hazard.

The ill treatment of African American seamen at Port Chicago was an old problem.

The year before, they had written a letter protesting conditions on the base, but nothing came of their complaint. On July 17, 1944, the inevitable happened.

Shortly after ten o’clock in the evening, the ten-thousand-ton

SS

E. A. Bryan

and the seventy-five-hundred-ton

SS

Quinalt Victory

exploded while seamen were loading an assortment of shells, depth charges, and bombs. Two horrific blasts, approximately

seven seconds apart, illuminated the sky in a golden-orange display of fire, smoke, and debris that reached several thousand feet. The blaze glowed for about ten minutes, then turned black. The explosion, which had the power of five thousand tons of TNT, was as intense as a small earthquake. Tremors were felt fifty miles away.

Everyone at the pier died instantly. The hulls of the big ships were shattered. The locomotive, boxcars, and pier were blown to bits. Seamen in the barracks were thrown from their bunks and hit by hot flying metal and broken glass. The wreckage seared the neighboring town, where some residents lost their homes, businesses, or eyesight.

The cleanup was as traumatic as the explosion. Authorities called in an army demolition team to remove unexploded weapons. Surviving seamen helped tend the wounded and gather up the floating heads, unattached limbs, and disfigured torsos of their comrades. Only fifty-one bodies could be identified.

The survivors suffered from flashbacks, sleep disturbances, heart palpitations, extreme nervousness, and hypersensitivity to sound. None received counseling. All, including those injured, were denied survivor’s leave.

The navy transferred the men to the nearby

Mare Island Naval Ammunition Depot and soon ordered them to resume loading munitions ships. Once they realized that conditions at Mare Island were essentially the same as those at Port Chicago, the seamen requested another work assignment. Their request was denied.

Terrified of another detonation and angry about how they were being treated, the seamen refused to load munitions. After efforts to get them to resume loading failed, the commander threatened to have them tried for mutiny and sentenced to death. Most returned to work, but fifty men, presumed by navy officials to be the leaders of the work stoppage, were charged with mutiny and conspiracy.

Murray cringed when she heard the prosecution characterize the seamen as depraved cowards. She sympathized with twenty-five-year-old

Freddie Meeks, who said, “

I am willing to be governed by the laws of the Navy and do anything to help my country win this war. I will go to the front if necessary, but I am afraid to load ammunition.”

The defense argued that the men’s refusal to load munitions was the result of paralyzing fear caused by the explosion, their injuries, the gruesome cleanup, and the imminent threat of another disaster. Of the seamen’s mental health, Dr.

Cavendish Moxon, a San Francisco psychoanalyst said, “

When men are shocked by an explosion into a serious state of panic, they are not free to undertake new risks or even normal activities

until they have been helped to overcome their nervous and mental upset.” To court-martial the seamen, Moxon maintained, was like punishing “

a neurotic for being unable to overcome his panicky fears.”

Present in the courtroom with Murray were NAACP counsel

Thurgood Marshall and

Edna Seixas, an African American woman affiliated with the Berkeley Interracial Committee. Marshall, who was gathering information for an appeal, said of the case, “

This is not fifty men on trial for mutiny. This is the Navy on trial for its whole vicious policy towards Negroes—Negroes in the Navy don’t mind loading ammunition. They just want to know why they are the only ones doing the loading!” Seixas, the mother of a serviceman killed in Italy, sat through the entire trial. She was not allowed to speak to the seamen, but “

her silent presence and kindly gaze” made them feel less alone.

On October 24, 1944, after thirty-two days and fourteen hundred pages of testimony, the all-white military court took little more than an hour to find the seamen guilty of mutiny and conspiracy. They were demoted and sentenced to prison.

Ten received a fifteen-year sentence, eleven got ten years, twenty-four got twelve years, and five received eight years. They were to be dishonorably discharged after serving their sentences.

· · ·

“

THE WHOLE THING has left me very disturbed,” Murray wrote to the first lady after the trial. For the men to be relegated to loading munitions because of their race and then punished after the explosion for refusing to resume loading seemed to Murray doubly unfair.

Edna Seixas wrote to Secretary of the Navy

James V. Forrestal, who had succeeded Frank

Knox, and asked for leniency in view of the “

terrible disaster” and discrimination the seamen suffered. While she acknowledged that the work stoppage was “untimely,” she argued that the men’s actions had broader significance. “I see not only 50 frustrated men and boys asking for a chance to do more than one dangerous assignment for their country,” Seixas said, “but all of the Negro people asking to do their part not only as burden bearers, but to share in all the work of the armed forces commensurate with their individual skills and training.”

Murray sent a copy of Sexias’s letter to ER, who read it “

with extreme interest” before passing it on with a note to FDR that said, “

Please read because I do think something might be done to make it a little easier.” The first lady could see “

how, in following the letter of the law, these men were considered guilty.” Even so, she sympathized with them and wished “

the verdict could have been different.” ER also sent Secretary

Forrestal the pamphlet

Mutiny? The Real Story of How the Navy Branded 50 Fear-Shocked Sailors as Mutineers

, which had been prepared under the auspices of the

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. She urged him to read the document and apply “

special care” in this case.

On November 15, 1944, Rear Admiral

Carleton H. Wright reduced the sentences of forty of the seamen, citing extenuating circumstances, their youth, and their prior good service records. Nonetheless, their felony convictions would stand and they would be ineligible for veteran’s benefits. The Port Chicago disaster would weigh into President

Harry S. Truman’s decision to issue

Executive Order 9981 on July 26, 1948, abolishing segregation in the United States armed forces.

On December 23, 1999, fifty-five years after the incident, President

Bill Clinton would pardon eighty-year-old

Freddie Meeks.