The Grand Ole Opry (13 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

The Ernest Tubb Midnite Jamboree, 1940s.

HAL SMITH, Texas Troubadour:

I remember women keeling over in Louisville when he sang there. They had to take them away on stretchers. He was as big as

Sinatra, only with a different, country audience.

Distressed when fans told him they couldn’t find his records, Tubb opened the Ernest Tubb Record Shop on Commerce Street,

Nashville, in May 1947. Although it was within walking distance of the Opry, more than seventy percent of the store’s business

was mail order. Tubb bought air-time on WSM after the Opry finished, and his Midnite Jamboree soon became a showcase for younger

talent.

From the earliest days, Opry shows were made up of regular performers along with guest artists, some of whom just happened

to be in Nashville on a Saturday night. Over the years, the concept of membership evolved, and by the 1940s it was fairly

formalized. In exchange for a commitment to perform regularly on Saturday nights at the Opry, members could use the Opry name

to advertise their road shows during the week. Though many of the earliest country stars—the original Carter Family, Jimmie

Rodgers, Charlie Poole, Jimmie Davis, Gene Autry—did not appear on the Grand Ole Opry, the addition of Pee Wee King, Roy Acuff,

Bill Monroe, Minnie Pearl, and Ernest Tubb made Opry membership the topmost rung of the country music business.

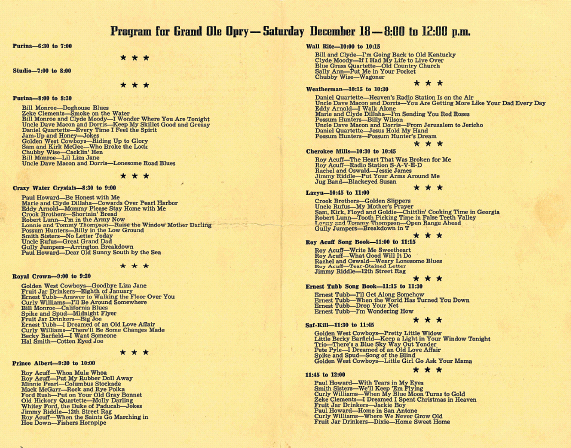

Grand Ole Opry program, December 18, 1943.

G

RAND

O

LE

O

PRY

NEW MEMBERS: 1940s

D

AVID

“S

TRINGBEAN

” A

KEMAN

E

DDY

A

RNOLD

T

HE

B

AILES

B

ROTHERS

R

OD

B

RASFIELD

L

EW

C

HILDRE

C

OWBOY

C

OPAS

T

HE

C

ACKLE

S

ISTERS

J

OHN

D

ANIEL

Q

UARTET

L

ITTLE

J

IMMY

D

ICKENS

A

NNIE

L

OU AND

D

ANNY

D

ILL

M

ILTON

E

STES AND

H

IS

M

USICAL

M

ILLERS

R

ED

F

OLEY

T

HE DUKE OF

P

ADUCAH

(W

HITEY

F

ORD

)

W

ALLY

F

OWLER AND

T

HE

O

AK

R

IDGE

Q

UARTET

P

AUL

H

OWARD AND

T

HE

A

RKANSAS

C

OTTON

P

ICKERS

J

OHNNIE AND

J

ACK

G

RANDPA

J

ONES

T

HE

J

ORDANAIRES

B

RADLEY

K

INCAID

L

ONZO AND

O

SCAR

C

LYDE

M

OODY

G

EORGE

M

ORGAN

M

INNIE

P

EARL

T

HE

P

OE

S

ISTERS

O

LD

H

ICKORY

S

INGERS

E

RNEST

T

UBB

C

URLEY

W

ILLIAMS AND

H

IS

G

EORGIA

P

EACH

P

ICKERS

H

ANK

W

ILLIAMS

T

HE

W

ILLIS

B

ROTHERS

COAST TO COAST

F

rom the time WSM station manager Harry Stone sold thirty minutes of the Grand Ole Opry to Crazy Water Crystals, there was

no shortage of sponsors. Manufacturers with products aimed at rural consumers, like Allis-Chalmers, International Harvester,

Penn Tobacco, and Carter’s Chickery, stood in line. But Harry Stone wanted to get at least a portion of the Opry on a national

radio network. WSM’s fifty-thousand-watt signal was strong, but reception outside the South depended upon location and atmospheric

conditions. If the Opry was on a network, it would be carried on local stations and come in clearly from coast to coast.

Harry Stone was especially keen to get a network slot because, in 1933, Alka-Seltzer began sponsoring a segment of the Opry’s

rival, Chicago’s WLS Barn Dance, on NBC’s Blue Network. WSM was already an NBC affiliate, broadcasting NBC network shows such

as

Amos ’n’ Andy, Vic and Sade,

and the

Lucky Strike Dance Hour

locally, but the Grand Ole Opry needed a sponsor to become a network show itself.

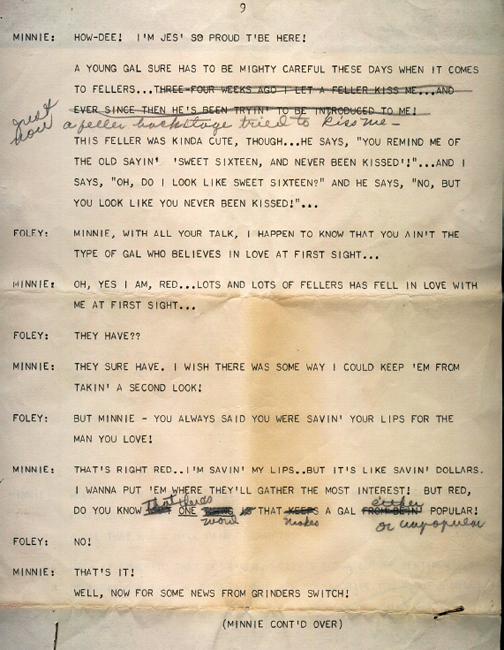

Page from a Prince Albert show script.

Another five years passed before one of the Opry’s newer sponsors, tobacco manufacturer R. J. Reynolds, approached NBC with

the idea of bringing thirty minutes of the show to the network. It was a good moment to take the Opry nationwide. The new

stars—Roy Acuff, Pee Wee King, and soon Bill Monroe and Minnie Pearl—were coming into their own. The country record business

was recovering from the Depression, and pop singers like Bing Crosby were beginning to “cover” country songs. Country music

was becoming a commercial force, and the Opry’s stars had just the right mix of modernity and tradition.

R. J. Reynolds’s Prince Albert brand sponsored the networked segment on what would become known as the Prince Albert Opry.

Although Roy Acuff had only been on the Opry little more than eighteen months, he was chosen as the host.

Roy Acuff and his Smoky Mountain Boys (and Girl) celebrate the Opry going coast-to-coast.

JUDGE HAY:

Various portions of the show had been sponsored for many years, so we who work behind the mics attached no particular significance

to the Prince Albert sponsorship at first. The arrangements were made by the William Esty Company, the New York advertising

concern, which handled the [Reynolds] account. Mr. Marvin there had the idea in the back of his head to put the Opry on the

NBC network. He came in for much ribbing [from] many members of his profession, but he stuck to his guns and found that there

was considerable interest in our efforts to entertain with homespun music and comedy. Heretofore, we had not made any effort

to produce the show in the accepted sense of the word, so we had to be snatched off the air at the end of our thirty minutes.

With that exception, the half-hour went over pretty well. Before the next week rolled around, we had timed our opening and

closing. The stations included in the Prince Albert deal were located all the way from the southeastern zone to the West Coast.

JUDGE HAY

introducing the first Prince Albert portion of the Grand Ole Opry, October 14, 1939:

Friends, these are the same people you’ve been listening to for fourteen years; the only difference tonight is that they’re

coming to you from the Mexican border to the mountains of Virginia. Our show is ready to ride right down the middle of the

road to our friends and neighbors throughout America.

JACK D

E

WITT:

The Prince Albert deal surprised me because I’ll never forget writing to the president of NBC, Bobby Sarnoff, son of the general

[NBC founder David Sarnoff]. I told him we had an awful lot of talent here and we’d like to put our programs on NBC. He wrote

back and said, “We’re not interested in country music. Perhaps you had better try CBS.” But you had the same attitude here

in Nashville. We started the first FM station [in October 1940] because Edwin Craig was embarrassed in front of the [upper

class] Belle Meade crowd because of the Grand Ole Opry. He thought that broadcasting classical music on FM would help.

With the Prince Albert sponsorship, nationwide Opry tours, and country songs taking over the airwaves, national magazines

began taking an interest in the Grand Ole Opry for the first time. Most of the pieces were patronizing, but the writers couldn’t

fail to be impressed with the Opry’s hold upon its audience or with the size of that audience.

DON EDDY,

journalist, in

American Magazine:

One 30-minute segment is piped over the full coast-to-coast NBC network, during which pollsters say it has 9,500,000 faithful

listeners. The cast varies from 120 to 137 performers, depending on how many show up. Pay is small (one featured singer gets

$19.50 a week) but advertising value to the individual is enormous. There are surprisingly few women on the show because (a)

women don’t like to be laughed at, and (b) backwoodsmen in the audience with their wives would get their ears slapped down

if they stared at a strange female, much less applauded her. That is why Cousin Minnie Pearl deliberately tries to make herself

homely.