The Grand Ole Opry (17 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

left: Listening to the Opry has always been a family affair, with something for every generation

right: Many people saved their battery power to listen to the Grand Ole Opry on Saturday nights. Some people even took the

battery out of their trucks to hook up to the radio.

JIM M

C

REYNOLDS

of Jim and Jesse in Carfax, Virginia:

We grew up in the mountains in Virginia, and the only entertainment we had was an old battery radio. On Saturday nights, the

whole family would gather in and listen to the Grand Ole Opry. Back then, if you were a member of the Opry, you were there

every Saturday night. You could always count on Monroe and Acuff and so on. We grew up in a family that played old-time music,

and you’d listen to the Opry on Saturday night, and you’d spend all next week trying to copy what you heard.

JEANNIE SEELY

in Titusville, Pennsylvania:

I was born in 1940, and I remember the times when Edward R. Murrow or President Roosevelt was on with announcements about

World War II, which I didn’t understand. All I knew was you had to be quiet. Then we’d turn on the Grand Ole Opry, and everyone

sang along and clapped. I couldn’t understand why it wasn’t always there. You should be able to always turn that button and

hear the Opry and Ernest Tubb. If we couldn’t pick up the Opry, we’d pile into the car and go find someone who could pick

it up.

PEE WEE KING:

I was substituting for Roy Acuff when President Roosevelt died. The Judge came to me and says to me, “Would you do your stage

show while the network takes over? Just entertain our audiences here at the Ryman?” I said, “Well, sure.” I told Buddy Harroll,

our trumpet player. “Buddy, run out in the bus and bring your ax in.” Buddy says, “King, you kiddin’? A trumpet on the Opry

stage?” I says, “Yeah.” I told the audience, “The network has taken over our radio time eulogizing our late president, so

if you don’t mind, we’d like to show you what we do in our stage shows. First, everyone, please bow your head in respect.”

I played “My Buddy” on the accordion. We had everybody in the audience in tears. Then Buddy went straight into “Bugle Call

Rag,” and Judge Hay almost jumped off the stage.

By war’s end, the Grand Ole Opry had become the most popular country music radio show, and every up-and-coming country star

wanted to work on it. The Opry offered something for everyone: old-time rural music from Uncle Dave Macon and Sam and Kirk

McGee; Bill Monroe’s bluegrass; Ernest Tubb’s honky-tonk music; Roy Acuff’s heartfelt Ap-palachian music; Minnie Pearl’s comedy;

Eddy Arnold’s crooning; and Pee Wee King’s sharp-tip western swing. The show was breathlessly fast-paced, designed in such

a way that if there was someone you didn’t like, you’d barely have time to reach the dial before he or she was off. The rapidly

evolving lineup and innovative managers behind the scenes would take the show to even greater heights in the years ahead.

STAR TIME

B

y the end of the Second World War, no one seriously questioned the Grand Ole Opry’s preeminence. There were hundreds of radio

barn dances on stations great and small, but the Opry was the dream of every performer on every small-town radio barn dance,

and the Opry’s management team was determined to keep it that way. But there were clouds on the horizon. For one thing, no

one foresaw the impact that television would soon have on “live” radio. When Pee Wee King left the Opry in 1947 to work on

a television station in Louisville, Kentucky, the feeling was that he’d be back in six months. Even so, as the Opry’s new

management team took shape in the years immediately after the war, the future looked rosy and assured.

Ott Devine, who would become manager of the Opry in 1959, George Reynolds, Jack Stapp, Harry Stone, and Judge Hay.

Judge Hay was still at the Opry, but only as an announcer. In 1945, he wrote the first history of the show,

A Story of the Grand Ole Opry.

It was a slender booklet sold only at the Opry’s concession stands, but it showed that the Solemn Old Judge already appreciated

the significance of what he’d created twenty years earlier. Vito Pel-lettieri still stage-managed the show, and Harry Stone

was still WSM station manager, but his brother, David, had left. The Opry’s former bouncer, Jim Denny, had taken over David’s

role at the Opry’s Artists Service Bureau. Shortly before the war, Jack Stapp had come to WSM as program director, and returned

after serving overseas. A quiet, diffident man, Stapp had worked at CBS radio in New York and helped professionalize the Opry.

Edwin Craig still oversaw the Opry from his position on the board of National Life, and brought back his old friend Jack DeWitt

to the newly created post of president of WSM. DeWitt was born on Fatherland Street in East Nashville, near where the Opry

was held between 1936 and 1939, but his interest in radio was almost entirely technical. As a part-time engineer, he’d helped

install WSM in the National Life building, and was chief engineer between 1932 and 1942. DeWitt’s appointment as president

placed him over Harry Stone, and this was probably Craig’s way of trying to limit Stone’s authority.

JACK D

E

WITT,

WSM president:

I came back to WSM in 1947. I used to go to the Opry every three or four months. I would go down and sit in the front seat

at the Ryman. Then I’d go backstage and see the guys. I wanted to show them that I had a great interest in the Opry, which

I didn’t at all. I like what’s called good music, but I didn’t let them know that if I could help it.

Jack DeWitt happily left the Opry to Harry Stone, Jack Stapp, and Jim Denny. They couldn’t risk a new star spearheading a

rival barn dance, so one of their top priorities was to recruit up-and-coming artists from other radio barn dances. The Opry

was still paying “scale” (the minimum mandated by the musicians’ union for broadcasts), but could entice young stars with

its prestige, huge listenership, and lucrative tours.

JACK STAPP:

The one thing I wanted to do was to get the best country talent at the Grand Ole Opry. Every time one of our artists would

say, “Hey, I just heard a great singer down in Shreveport, you ought to get him,” I’d get on the phone and I’d call him. I’d

ask him if he wanted to come to Nashville.

The answer was almost invariably “Yes.”

MARIE CLAIRE,

Jim Denny’s assistant:

Jim Denny greatly improved the quality of country bookings through the bureau. Where Opry acts once played schoolhouses and

tiny halls, Denny had them in auditoriums, arenas, and fairs. He had a deep, gruff voice. He liked to wear brown pinstriped

suits, and he walked down the hall like a bear. He scared some people to death.

Jim Denny had come to Nashville on his own at age eleven in 1922. Jim Denny: “I got off the train and all my money was in

a little tobacco sack. I had about forty cents. I got a job selling the

Tennessean

up and down Church Street. Between editions, I delivered telegrams, and I was adopted, sort of, by the women in the bordellos

north of the Capitol. Most of their business was arranged by telegram. Very often, answers were required, so I got to carry

the messages both ways. They were always good for a fifty-cent tip, a good meal, and conversation.”

The first problem facing the new management in the postwar years was how to handle an Opry star who sometimes gave the impression

that he was bigger than the show itself: Roy Acuff. The host of the Opry’s networked Prince Albert show, Acuff was not only

the biggest star in country music, but one of the biggest stars in all popular music. War reporter Ernie Pyle reported that

the Japanese troops at the Battle of Okinawa screamed, “To hell with Roosevelt! To hell with Babe Ruth! To hell with Roy Acuff!”

When National Life salesmen went on the road, they were trained to say, “Good morning, I work for the company that owns the

Grand Ole Opry, and Roy Acuff asked me to come by and give you a personal hello. May I come in?”

The war in Europe was over, but hundreds of thousands of GIs remained there, and, with the fighting ended, they could focus

a little more upon entertainment. Their choice: Roy Acuff and the Smoky Mountain Boys.

THE FIRST CARNEGIE HALL SHOWS

No event better underscored the fact that country music had a nationwide following than the first Carnegie Hall concerts in

September 1934.

Billboard

magazine, November 1947:

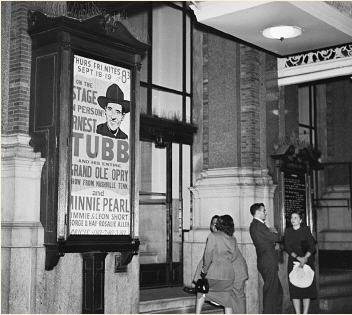

Staid Carnegie Hall has been re-bopped by Lionel Hampton and jived by Woody Herman, but Thursday and Friday September 18 and

19, it was corn-quered by hillbilly music and the place will never be the same again. A cornbilly troupe called the Grand

Ole Opry featuring many performers appearing regularly on the air show of that name took over the house and proved to the

tune of $12,000 gross that the big city wants country music. The promoters, Sol Gold, Abe Lackman and Oscar Davis, got more

than a kick out of it because they garnered about $9,500 with a talent nut of about $5,000. If nothing else, the hillbilly

concerts demonstrated several important things. First, New York is sold on hillbilly music. These weren’t just curious onlookers

out for a night of novelty. These were serious devoted fans, almost rabid in their wild enthusiasm. Such screaming and wild

applause after each number hasn’t been heard in town since Frank Sinatra brought out the bobbysoxers at the Paramount. Instead

of juveniles, these were people beyond their teens who knew all the numbers and entertainers, which is proof positive that

they listen to all the shows featuring these performers.

From the

Grinder’s Switch Gazette,

September 1945:

Word has just now reached us that last winter for almost six months the Roy Acuff recording of “Great Speckled Bird” was among

the top ten numbers on the Mediterranean Hit Parade chosen from requests sent in by G.I.s in that section of the world.

From

Radio Daily,

October 1945:

A tally of 3,700 votes cast by G.I. listeners in the European areas during a two-week popularity contest over AFN’s

Munich Morning Report

between Frank

MINNIE PEARL:

That was the first time I realized how far-flung country music had become. The boys had come home from the service and many

who’d never been exposed to country music before they left were now fans. It’s hard for some of the new country artists to

realize how limited we were in the early days. Through the mid-1940s, country music performers didn’t play the big halls or

the class houses. We showed in high school auditoriums, one-room schoolhouses, beer joints, and fairs.