The Grand Ole Opry (18 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

ERNEST TUBB:

People couldn’t believe country music was being played at Carnegie Hall. The radio and newspaper people ignored us the first

night we were there, but we turned away six thousand people and the next night every reporter was there. We played two nights

and even then didn’t play to everyone.

Sinatra and Roy Acuff showed a 600 vote lead for Acuff. As a result, a new show called

Hillbilly Jamboree

will be launched by AFN Munich soon.

From the

Grinder’s Switch Gazette,

November 1945:

While Roy Acuff is in Hollywood, Saturday night Opry fans will still be able to hear him and the Smoky Mountain Boys on the

Prince Albert program. Arrangements have been made to “pipe” his part of the program from Hollywood through to WSM, where

it will go out as part of the network show.

Despite characterizing Hollywood as seventy-five percent phony, Acuff made five movies between 1942 and 1946, and toured nationwide,

making it hard to meet his Opry commitment.

Before satellites, radio shows were transmitted across the network by phone lines, and Roy Acuff used the same technology

to appear on the Opry in voice if not in person.

From the

Grinder’s Switch Gazette,

January 1946:

A lady arrived at the Opry House back in November and was walking down the aisle to her seat just as Roy Acuff by wire from

Hollywood was introducing Gene Autry, also in Hollywood. Autry sang a song. The lady, being familiar with the voices of both

Roy and Gene was somewhat confused hearing them and not being able to see them. She walked up to the doorman and said, “How

much extra does it cost to see ’em?”

Roy Acuff was beginning to test his popularity in ways that sometimes dismayed his costars. In 1943, Acuff’s Prince Albert

Opry show had gone from partial networking to the full NBC network. There was a celebration at the Ryman, but Tennessee governor

Prentice Cooper wouldn’t attend. Saying he’d be no party to a circus, he added that Acuff was bringing disgrace to Tennessee

by making Nashville the hillbilly capital of the United States. He would be the last Tennessee governor to take that stand,

but Acuff was determined to make him pay for it. With a governor’s race looming in 1944, Acuff secured the Republican nomination.

PEE WEE KING:

Roy called me before he announced his candidacy. He said, “Pee Wee, you’re a Republican, and I want you to help me. I’ll throw

in fifty thousand dollars of my own money, and we’ll draw crowds like you’ve never seen. We’ll play all the little foothill

towns and courthouse squares all over Tennessee, and I’m confident we’ll win.” He was right about drawing the big crowds.

Everybody came to hear ol’ Roy sing, but they didn’t vote for him. He got whipped by the Democrats.

Roy was the first Opry star to sign a deal for product endorsement. Cherokee Mills reached an agreement with him to use his

name on their flour. Later in the 1940s, J.C. Penney would license his name for a line of clothing.

Undeterred, Acuff decided to try for the Republican nomination again in 1948, but was defeated yet again.

In 1946, between runs for governor, Roy Acuff left the Opry in a dispute over salary. Rather than give in to his demands,

the Opry hired Red Foley away from WLS’s National Barn Dance to replace him on the Prince Albert segment.

Roy Acuff: “It isn’t easy for a country boy like me to stand up here and try to make a political speech. I intend on staying

up here, being one of you, and I promise not to bring politics again to the Grand Ole Opry.”

RED FOLEY:

I guess I never was more scared than I was the night I replaced Roy Acuff on the network part of the Opry. The people adored

Roy and a lot of them didn’t believe he’d quit. They thought I was a Chicago slicker who had come down to pass himself off

as a country boy and bump Roy out of his job. It took me about a year to get adjusted. But, boy, that first night on the Opry

stage was a nervous time. While I was wishing Roy luck and saying goodbye, there were old women crying in the front row. I’d

been warned people might throw tomatoes at me—without taking them out of the can.

HILLOUS BUTRUM,

Opry bass player:

Foley wasn’t a real showman, but I’ve never seen anybody else able to hold an audience the way Red did, except maybe Hank

Williams. We were playing the Showboat in Las Vegas once, and everybody was drinking and gambling and living it up. Red came

out and did “Peace in the Valley,” and it was like someone had turned off a switch. We asked him how he had the nerve to sing

a hymn in a place like that and how he could make it go over so strongly, and he said, “I pick out two people and just sing

to them. I begin to reach them, and then it spreads.”

Early in 1947, Roy Acuff returned from an extensive West Coast trip, and was hospitalized. Two of his first visitors were

Harry Stone and Ernest Tubb. According to Acuff, the conversation went like this:

Harry said, “Roy, the Opry is losing many of its people, and it looks like maybe we’re going under if you don’t come back

and be with us. Come and help us out. We wish you would change your mind, and come back.” [I replied], “Harry, if I mean that

much to WSM and the Grand Ole Opry, I will come back and do everything I can to help the Opry at all times.”

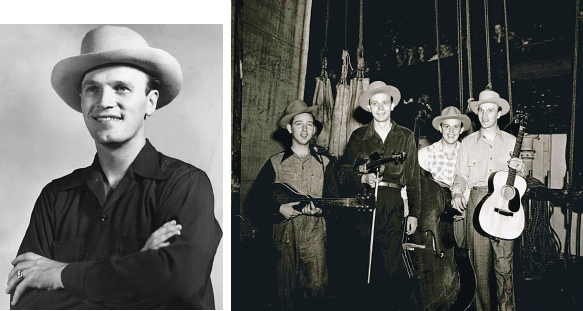

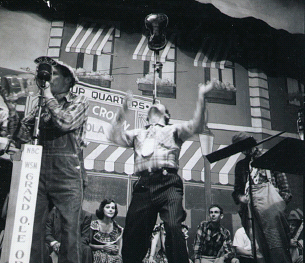

Roy Acuff in a promotional shot for RC Cola.

Roy Acuff returned April 26, 1947, as host of the Opry’s Royal Crown segment, but Red Foley remained at the helm of the Prince

Albert show. Always an astute businessman, Acuff might have sensed that his career had peaked. He returned just as another

Opry star, Eddy Arnold, was wondering if he really needed the Opry. Arnold’s answer would be different than Acuff’s. A pioneer

country crooner, Eddy Arnold’s star had risen meteorically in very few years. It had been just five years since he’d left

Pee Wee King and gone to see Harry Stone.

Roy Acuff was a showman extraordinaire. In addition to singing and playing the fiddle, he was a champion with a yo-yo and

could balance a fiddle on its bow on his chin.

EDDY ARNOLD:

I said, “Mister Stone, I love Pee Wee, but I’m going to leave him. I’m not making any money and I’m not getting anywhere.

I have a wife and mother to support, and I’m quitting whether you hire me on my own or not. What I’d like to do is work for

you on this station.” How I ever got up the nerve to askHarry Stone to give me my own program, I’ll never know. Mister Stone

looked at me a second or two, blinked, and said, “Eddy, you have a job.” I didn’t earn a lot on WSM, but Harry Stone saw to

it that I got enough to get by. I’ll never be able to repay Harry Stone for having faith in me. Gradually, he arranged for

me to appear on other WSM programs, and finally the Grand Ole Opry.

In 1944, Harry Stone arranged for Eddy Arnold to get a recording contract with RCA, and in the years immediately after the

war, Eddy sold millions of records and became the first country artist to consistently cross over into the pop charts. He

dominated the country charts to such an extent that just one other artist scored a number-one hit in 1948.

Eddy’s Arnold’s manager, Colonel Tom Parker, later managed Elvis Presley, and saw the Opry tying up his star on Saturday night

at minimum wage. Repeatedly, the Colonel told Eddy that the Opry needed him more than he needed the Opry, and, in 1948, Eddy

came to share that opinion.

EDDY ARNOLD:

Someone said to me, “The Opry made you.” I said, “If it made me, then why hasn’t it made the Fruit Jar Drinkers?”

Even off the Opry, Eddy Arnold was so influential that the Opry had to accommodate him. Colonel Parker arranged for Eddy to

host a radio show sponsored by Purina. It was offered to WSM for transmission on Satur-day night, but WSM turned it down because

it would interrupt the Opry. Purina then offered it to WSM’s rival, WLAC, for Friday night.