The Grand Ole Opry (20 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

Whistlin’ Dixie. From left: Hank Williams, Jerry Rivers, Sammy Pruett, Cedric Rainwater, and Don Helms; seated, Minnie Pearl.

CHET ATKINS,

Opry staff guitarist:

Hank would come up to you at the Opry and say, “I got a new one for you, hoss.” He’d get right up in your face and sing it,

and the smell of bourbon would be pretty strong. Then he’d play something like “Mansion on the Hill,” or one of those unbelievably

great songs. Someone like Ernest Tubb or Hank Snow would be standing around, and they’d say, “I’d like to record that, Hank.”

Hank would narrow his eyes and say, “Naw, it’s too damn good for you. I’m gonna record it myself.” I think those were his

test runs. If Ernest Tubb and Hank Snow wanted the song, Hank knew it was a hit.

Even the mainstream press was beguiled by Hank’s enigma, especially after his songs, like “Cold, Cold Heart,” “Jambalaya,”

and “I Can’t Help It,” became pop hits for Tony Bennett, Frankie Laine, Jo Stafford, and others.

RUFUS JARMAN,

journalist, in

Nation’s Business:

He is a lanky, erratic country man who learned to play guitar from an old Negro named Teetot in his home village of Georgiana,

Alabama. “You ask what makes our kind of music successful,” he says. “I’ll tell you. Just one word: sincerity. When a hillbilly

sings a crazy song, he feels crazy. When he sings, ‘I laid my mother away,’ he sees her a-laying right there in the coffin.

He sings more sincere than most because he was raised rougher than most. You got to know a lot about hard work. You got to

have smelled a lot of mule manure before you can sing like a hillbilly. There ain’t nuthin’ queer at all about them Europeans

liking our kind of singing. It’s liable to teach them more about what everyday Americans are really like than anything else.”

For a couple of years, Hank raced back to Nashville almost every Satur-day night. He knew that the Opry was the most exclusive

club in country music, and knew that he’d worked hard to get there. But that would eventually change as he grew more successful.

Hank Snow had recorded in Canada since 1936, but encountered only disappointment in trying to broaden his career into the

United States. The Opry was still signing artists like Jimmy Dickens and George Morgan, who didn’t have hits, but the show’s

management was as resistant to Hank Snow as they’d been to Hank Williams. Snow, though, had a champion on the Opry in Ernest

Tubb. The two shared a fanatical passion for Jimmie Rodgers, and Tubb promised to do his best to get Snow onto the show.

HANK SNOW:

I could hear the Opry in eastern Canada pretty well. I wrote to Ernest [Tubb] in care of the Grand Ole Opry and got a nice

letter back, and we corresponded. Ernest said, “Hank it’s all happening in Nashville. Nashville is the home of country music.

If you want to advance your career you should be there. I’ll do my best to get you on the Opry, but there’s one problem: they

won’t sign anyone unless they have a hit record.”

Tubb tried to interest Harry Stone in hiring Snow as a replacement for him while he was on the West Coast. According to Tubb,

the conversation between Stone and himself went like this:

“Well, what do you think?”

“He sounds too much like you.”

“Ah, don’t gimme that stuff. I’m talking long distance and I’m spending my money. I’ll argue with you when I get home. He

sings like he’s a Jimmie Rodgers fan, but with that Canadian brogue, he can’t sound like me.”

Hank Snow was working at the Big “D” Jamboree in Dallas when Tubb finally persuaded Jim Denny to take a chance on his friend.

HANK SNOW:

I got a phone call from Ernest. “Hank, I had a talk with Mister Denny. He thinks he’ll be able to place you on the Opry.”

I was wondering how Ernest had convinced Mister Denny. After all, I still didn’t have a hit record in the USA. Mister Denny

didn’t say anything about a tryout. He said he wanted me to start on January 7, 1950, at seventy-five dollars a week. I said

many prayers during the few weeks before my Opry debut that I would be a success. God has his plan for all of us, even a little

weakling from Nova Scotia, Canada.

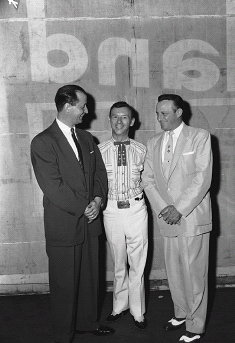

From left, Jack Stapp, Hank Snow, and Jim Denny, backstage.

On March 28, 1950, Hank Snow recorded his first Amer ican hit, “I’m Movin’ On,” and the Opry stage provided ready-made audience

of around ten million.

HANK SNOW:

All the years of frustration came together with just one song. Mister Denny confirmed my fears. He said, “A few weeks ago,

Harry Stone heard you sing for the first time. He said, ‘Who the hell is that out there trying to sing?’ I can tell you now,

‘I’m Movin’ On’ is a miracle if ever there was one. They were about to drop you.” The Opry audiences changed overnight. They

were completely indifferent one week, and the next week they were wildly enthusiastic.

The new stars not only ensured that no other radio barn dance would eclipse the Grand Ole Opry, but the concentration of so

many country stars in one place meant that the business would soon follow them to Nashville.

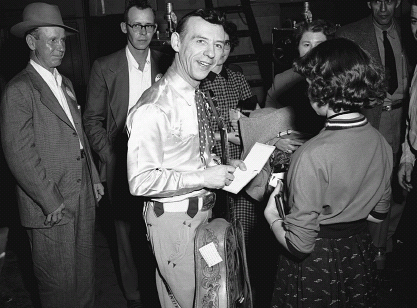

Hank Snow greets fans backstage at the Opry.

G

RAND

O

LE

O

PRY

NEW MEMBERS: 1950s

C

HET

A

TKINS

M

ARGIE

B

OWES

C

ARL AND

P

EARL

B

UTLER

A

RCHIE

C

AMPBELL

T

HE

C

ARLISLES

M

ARTHA

C

ARSON

M

OTHER

M

AYBELLE

C

ARTER AND THE

C

ARTER

S

ISTERS

J

OHNNY

C

ASH

C

EDAR

H

ILL

S

QUARE

D

ANCERS

C

OUSIN

J

ODY

W

ILMA

L

EE AND

S

TONEY

C

OOPER

S

KEETER

D

AVIS

R

OY

D

RUSKY

T

HE

E

VERLY

B

ROTHERS

L

ESTER

F

LATT AND

E

ARL

S

CRUGGS

C

HET

A

TKINS

M

ARGIE

B

OWES

C

ARL AND

P

EARL

B

UTLER

A

RCHIE

C

AMPBELL

T

HE

C

ARLISLES

M

ARTHA

C

ARSON

M

OTHER

M

AYBELLE

C

ARTER AND THE

C

ARTER

S

ISTERS

J

OHNNY

C

ASH

C

EDAR

H

ILL

S

QUARE

D

ANCERS

C

OUSIN

J

ODY

W

ILMA

L

EE AND

S

TONEY

C

OOPER

S

KEETER

D

AVIS

R

OY

D

RUSKY

T

HE

E

VERLY

B

ROTHERS

L

ESTER

F

LATT AND

E

ARL

S

CRUGGS

J

IM

R

EEVES

M

ARTY

R

OBBINS

J

EAN

S

HEPARD

C

ARL

S

MITH

H

ANK

S

NOW

R

ED

S

OVINE

S

TONEY

M

OUNTAIN

C

LOGGERS

T

ENNESSEE

T

RAVELERS

J

USTIN

T

UBB

P

ORTER

W

AGONER

K

ITTY

W

ELLS

T

HE

W

ILBURN

B

ROTHERS

D

EL

W

OOD

F

ARON

Y

OUNG

DEPARTURES AND ARRIVALS

T

he Grand Ole Opry had begun as just another show on WSM, but by 1950 it was bigger than the station itself. It was still heard

on WSM, but more than 160 other NBC stations picked up part of the show, and it went out over Armed Forces Radio as well.

People were beginning to say “Grand Ole Opry” when they meant “country music.” Management of the show became a prize worth

fighting for, and, in the early 1950s, a power struggle unfolded between Harry Stone and Jim Denny.

Harry Stone at the helm. In 1950, Judge Hay wrote, “Harry’s hobby is his cruiser on the Cumberland River, in which he gains

relaxation after a tough day at the office. He named his boat the

Grand Ole Opry.

Let us assure our audience that the job of managing one of America’s largest broadcast stations is a big one, fraught with

many diverse problems.”

JACK D

E

WITT:

Harry Stone was a good radio man. When we, WSM, had contracts with the companies that advertised on the Opry, Harry was very

good at dealing with them. Unfortunately, it got to the point where he was taking money from them, and that’s when we fired

him. Up to then, he completely refused to cooperate with me, and wouldn’t have anything to do with reporting to me. The interesting

thing is that both Jim Denny and Harry Stone were very stricken with a girl named Dollie Dearman. Harry had this boat that

he kept down on the river, and one of our announcers, Louie Buck, came to me one time with a picture of [Dollie Dearman] on

that boat. She was all spread out with nothing on. I didn’t know that Louie knew Greek mythology, but he said, “This is the

one that launched a thousand ships.” Anyway, Stone went out to Arizona, and Denny finally married her. His wife divorced him

and he married her.