The History Buff's Guide to World War II (30 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

British soldiers killed in the first three months of World War I: 50,000.

British soldiers killed in the first three months of World War II: 1.

3

. THE PEOPLE’S WAR

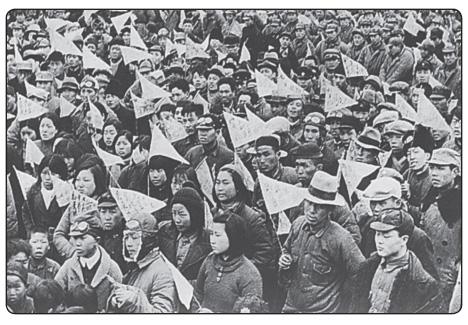

In an attempt to unite their disparate populations, leaders frequently presented their national struggle as a “people’s war.” Rich and poor, left and right, young and old were brought together with an “us against them” approach. The title was almost automatic in Communist-held northwest China and the Soviet Union. Though used occasionally elsewhere, it took root deeply in an unlikely place.

When war erupted in 1939, the British were in no way enthusiastic about marching back into the breach, especially with recollections of Flanders fields. Many asked, “Why die for Danzig?” while twenty-two out of Europe’s twenty-seven countries remained neutral.

Yet the traditionally class-divided British began to find unity in hardship. Large-scale urban evacuations, worker shortages, and homeland defense operations created an intermixing of previously separate castes. Laborers of all levels of skill and education worked together in munitions plants. Citizens from every station joined in the original melting pot—the armed forces. Bombs were not selective about which class they fell on. With misery came interaction and interdependence, the likes of which peacetime did not provide.

50

The nation truly found its war footing with the abrupt and astonishing fall of France in 1940 and its climactic “Miracle of Dunkirk.” Over the course of ten days, a flotilla of ships and boats—French, Belgian, Dutch, and Commonwealth British—came together to rescue more than one hundred thousand French and two hundred thousand British troops from almost certain Nazi capture. Thereafter, “People’s War” was in common use. Though far less harmonic or selfless than was commonly portrayed, the war was quite possibly “their finest hour,” when the crowd rather than the Crown became the substance of the kingdom.

51

China lost more than five citizens for every soldier killed, whereas the United States lost hundreds of soldiers for every civilian who died.

Three out of four rescue ships at Dunkirk were civilian, many of them simple fishing boats.

4

. THE WAR OF RESISTANCE

Unlike Australia, Britain, Japan, and the United States, most of the war’s combatants experienced periods of either partial or total foreign military occupation. Many used “War of Resistance” to describe their struggle.

The Kremlin heartily promoted “Resistance to Fascist Oppression.” After the fall of Paris in June 1940, Charles de Gaulle appointed himself the leader of the Free French and declared, “The flame of French resistance should not be extinguished.” Among other subversive groups in occupied Holland was the Raad van Verzet, or Resistance Council. Both Mao Zedong’s Communists and C

HIANG

K

AI

-S

HEK’S

Nationalists called their fight Kanri zhanzheng (the War of Resistance).

As with the last case, foreign invasion often provided a common enemy, bringing bitter rivals together. In France, Communists and nationalists joined in combating the Germans. Josip Broz, better known as Tito, brought together Serbs, Croats, and Muslims in his resistance movement. Communists, nationalists, and royalists in Greece joined the resistance against fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Unfortunately, this sense of unity often disintegrated once the invaders departed.

Few cities or villages in northern France don’t have a plaza or street named “Le Résistance.”

5

. THE HOLY WAR

Religion, history’s baptismal font of conflict, was not a major cause of World War II. Participants nonetheless sought the heavens for divine inspiration and claimed their own mission as the most righteous. Americans sang “Onward Christian Soldiers” almost as often as they crooned “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition.” The British Royal Navy ordered all ships of cruiser size and above to install chapels. In their fight against “godless Bolsheviks,” the German Wehrmacht wore belt buckles stamped Gott Mit Uns (“God is with us”).

Secular and clerical circles presented the war as a showdown between good and evil. Nearly every national leader used the pious term “holy war” several times in public, along with other dutiful tags such as “sacred cause” and “crusade.” Officially agnostic

Pravda

printed V. I. Lebedev’s poem “Holy War” just two days after the German invasion, and its stanzas were set to music soon after. Stalin, a former seminary student, christened the “Sacred War” with sermons on “Holy Russia.”

52

More than any other nation, Japan defined the global conflict as a divine test of souls. “Holy War” remained central in word and deed, anchored by a faith in an emperor seen as the embodiment of providence upon earth. In a far less reverent medium, Japanese cartoons often illustrated the “Holy War” concept. Whereas American and British propaganda often drew the Japanese as toothy, bespectacled simians, Japanese illustrators advertised their enemy as purely satanic. Caricatures of Roosevelt, Churchill, Uncle Sam, and John Bull invariably featured horns, tails, clawed forelegs, and hoofed hindquarters. Allied soldiers and sailors were also drawn in devilish guise, presented as poised and ready to instill wicked wrath upon sacred Asia and the whole world.

53

Through religion, civilians sought salvation while governments sought justification.

During the Second World War, 8,896 chaplains served in the U.S. Army.

6

. THE GREAT PATRIOTIC WAR

Czarist Russians referred to Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1812 march on Moscow as “the Patriotic War.” When Adolf Hitler repeated the march in 1941, Soviet leaders declared the new struggle Velikaia otechestvennia voina (“the Great Patriotic War”).

54

Suddenly, warm nostalgia replaced cold ideology. Rather than comrades fighting for communism, “brothers and sisters” were fighting for “Mother Russia.” Instead of Lenin and Marx, movies glamorized Russian heroes like Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible. Speeches and songs recalled triumphs over foreign hordes, particularly German ones.

55

Most Russians expressed their patriotism in words as well as deeds during the war. Soldiers marched into battle without weapons. Civilians transported factories brick by brick to the security of the Urals. In foundries and on farms, people labored fifteen hours a day and more, subsisting on near-starvation diets. Many willingly suffered “for country and home.” Of course, along with this jingoist fervor, Russians also had two additional motivations: fear of Hitler and fear of Stalin. To this day, “the Great Patriotic War” remains the official Russian title of the conflict.

56

All in all, Hitler fared better against the Russians than Napoleon. Der Führer lost approximately 60 percent of his forces in three years, whereas the Little Emperor lost 90 percent of his Grande Armée in six months.

7

. ANOTHER THIRTY YEARS’ WAR

Connecting 1914 with 1944, Europeans labeled the period “another Thirty Years’ War.” Public usage of the term emanated from Winston Churchill, Charles de Gaulle, and exiled Czechoslovak president Edvard Benes. To them and others who personally experienced two massive wars in one lifetime, World Wars I and II were essentially the first and second acts to a tragedy in which Germany was the continual antagonist. The only difference seemed to be the cast of characters.

57

There were definitely similarities between the seventeenth-century war and its twentieth-century counterparts. The 1618–48 version also featured Germany, cost millions of lives, occurred in phases, and introduced new and unwelcome methods of warfare, including mobile artillery and rapid-firing infantry.

To some observers, history verified Germans as inherently militaristic. Scholars hypothesized of a German Sonderweg or “peculiar path,” whereby the Fatherland failed to follow the “natural progression” of modern nation-states, somehow remaining fundamentally barbaric. In turn, German nationalists countered the Sonderweg theory by reminding Britain and France of their own particularly bloody histories wrought with ruthless revolutions, civil wars, ventures of conquest, and centuries of less-than-benevolent-treatment of colonial subjects.

58

In the First and Second World Wars put together, approximately 14 percent of the German population died. In the Thirty Years’ War of 1618–48, at least 25 percent of the German population was killed.

8

. THE GREATER EAST ASIAN WAR

Beginning with the R

usso

-J

apanese

W

ar

, Japan rationalized its territorial expansion as the natural progression of an industrialized country, much in the same vein as “manifest destiny,” “Lebensraum,” or “Rule Britannia.” These paths went from parallel to confrontational in 1941, when Tokyo’s designs targeted European and American holdings in Asia and the Pacific.

Any chance to share the spoils ended on December 7, when Imperial air and naval forces launched simultaneous attacks on British Hong Kong, the American Philippines, Honolulu, and elsewhere. From then on, the empire officially called the conflict Dai Toa senso (“the Greater East Asian War”) and presented the conflict as a grand “counteroffensive of the Oriental races against Occidental aggression.”

59

Initially, some sincerely believed the Japanese were acting as liberators. Several thousand Burmese, Malayans, Filipinos, Okinawans, and others assisted or fought in concert with Imperial forces. Others collaborated in hopes of removing the Western presence from their midst. But over time the Japanese demonstrated an equal or greater talent for repression. Consequently, most Asians turned against their Japanese “saviors,” aiding the downfall of an empire that at its peak stretched from the Indian Ocean to the Aleutians.

60

In December 1945, Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s occupation headquarters forbade the use of “Greater East Asian War” in Japanese public discourse because its meaning was viewed as inherently nationalistic. Henceforth, the only acceptable term was to be Taiheiyo senso (“The Pacific War”).

61

Today, an ongoing feud continues within Japan’s school system on what to call the Second World War. Educators who wish to emphasize national pride call it “the Greater East Asian War,” whereas others who wish to present Japan as a member of the international community teach it as “the Pacific War.”

9

. THE FIFTEEN YEARS’ WAR

Time may heal all wounds, but it also functions as a naming convention for historical events. Such was the case in the 1940s when people grieved over “the interminable war” and later applied more precise measures to its elements. Leningraders suffered through “the Nine Hundred Days” when German forces surrounded and nearly leveled the Baltic city. Allied bombers flew more than three thousand sorties in “Big Week,” in actuality a six-day hammering of German aircraft factories in February 1944. Westerners still refer to the Allied invasion of Normandy as “the Longest Day.”

After 1945 Asians spoke of “the Fifteen Years’ War,” especially those who wished to enunciate the duration of Japanese military aggression. Measuring from the 1931 M

ANCHURIA

I

NCIDENT

, the term encompassed the plethora of subsequent “incidents” between Chinese and Japanese troops in the 1930s, the full-fledged invasion of China in 1937, pitched battles with the Soviet Union along the border of Outer Mongolia in 1939, and the spread of war into the Pacific in December 1941. A few former members of the Japanese military also used the title, in part because it implied that Japan lasted twice as long as its Axis partners.

62