The History Buff's Guide to World War II (34 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Ingenious but unreliable, Me-262s revolutionized aeronautics but had negligible effect on the war.

Overall, four types of jet planes flew in combat, three German and one British. The RAF’s twin-engine Gloster Meteor was used primarily to shoot down V-1 buzz bombs. In seven months, sixteen operational Meteors scored just thirteen V-1 kills.

16

7

. FIRST FLYING BOMB (JUNE 1944)

Predecessor to the cruise missile, the V-1 represented the most effective of Germany’s secret weapons. It also exemplified the crippling lack of coordination within the Third Reich.

Resentful of the funds and attention granted to the army’s rocket program, air force marshal H

ERMANN

G

ÖRING

pushed development of a pilotless flying bomb. Rather than share technicians and facilities, the Luftwaffe openly competed with the army, slowing down production on both projects and further damaging a military wrought with petty quarrels and overlapping responsibilities.

17

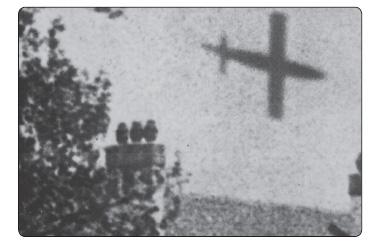

Less expensive and simpler than the army’s rocket, the Luftwaffe’s experiment reached completion first. Looking like a bird of prey with wings outstretched, it flew by the power of a pulse-jet engine (ironically a French innovation), which produced a spine-rattling metallic flutter, earning it the nickname “buzz bomb” or “doodlebug.” The German Ministry of Propaganda dubbed it “die Vergeltungswaffe” or “Vengeance weapon,” V-1 for short.

18

A V-1 buzz bomb, its pulse jet shutting off, slowly turns over as it descends into a London neighborhood.

Vengeance first materialized on June 13, 1944, just days after the Allied invasion of Normandy. Four bombs fell on London. Two days later, two hundred came, then thousands in the following weeks. One landed directly on a chapel during services, killing 121 churchgoers almost instantly. Winston Churchill confessed the V-1 brought “a burden perhaps even heavier than the air-raids of 1940 and 1941. Suspense and strain were more prolonged. Dawn brought no relief, and cloud no comfort.”

19

Overall, Germany launched more than twenty-two thousand V-1s, with nearly seven thousand reaching their targets in Britain, Belgium, France, and Holland, killing an average of two people per bomb.

20

On June 17, 1944, one buzz bomb strayed far off course and hit a German bunker in eastern France. Though shaken, the shelter’s occupants escaped uninjured, including one Adolf Hitler.

8

. FIRST LIQUID-FUELED BALLISTIC MISSILE (SEPTEMBER 1944)

In late August 1944 the Allies liberated Paris, but the euphoria was short-lived. On September 6 an altogether new weapon terrorized the city, falling from the sky faster than sound. Two days later the same deadly device hit London. Suddenly no point in Allied Europe appeared safe.

After nearly a decade of development, German engineers successfully transformed Robert Goddard’s 1926 invention for interstellar exploration into the first operational liquid-fueled ballistic missile, called the A-4, renamed “Vengeance Weapon 2.” Nearly four stories tall, capable of traveling two hundred miles in five minutes, and armed with a one-ton warhead, the rocket was unsurpassed in its ability to induce fear. One young boy in London recalled, “Of all the Nazi’s weapons, we were most afraid of the V-2 because there was no way to stop it.”

Though the V-2 ultimately played a secondary role in the war, the weapon signaled the beginning of an entirely new type of warfare and inspired the U.S. and Soviet governments to capture—and then employ—as many of its creators as possible.

21

Wernher Von Braun worked as the chief guidance system engineer for the V-2. He later became deputy associate administrator of NASA.

9

. FIRST ATOMIC BOMB (JULY 1945)

Six weeks after the Nazi invasion of Poland, Roosevelt received a letter from Albert Einstein. The renowned physicist suggested the possibility of constructing a bomb using fissionable material, namely uranium: “A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory. However, such bombs might very well prove to be too heavy for transportation by air.”

22

A series of recent findings influenced Einstein’s prediction. The neutron was discovered in 1932, as was Uranium-235 in 1935. In early 1939 French and American scientists theorized that a chain reaction of U-235 neutrons was possible and would release “vast amounts of power.”

23

A radioactive plume ascends from devastated Hiroshima, the second-ever atomic detonation.

German, Japanese, Soviet, British, and American governments all sponsored investigations into the feasibility of atomic weapons. By 1943 Germany and Japan opted out due to critical setbacks in research and resources. Soviet progress lagged from two years of land war with Germany. Only British-American cooperation found success, fostered by secure U.S. manufacturing sites and massive funding.

24

A budget of two billion dollars, a work force of forty thousand people, and nearly four years of continuous work resulted in the construction of three devices. The first, armed with plutonium (U-238 with an additional neutron), tested successfully on July 16, 1945, outside Alamogordo, New Mexico. Three weeks later came the first atomic weapon used in wartime. Contrary to Einstein’s assumption of its required size, the entire apparatus could be carried by a four-engine aircraft, but his estimation of its force was on target. The U-235 bomb, nicknamed “Little Boy,” detonated above the port city of H

IROSHIMA

, Japan, decimating four square miles and killing at least one hundred thousand people. Three days later a plutonium bomb, called “Fat Man,” exploded above Nagasaki, killing at least seventy thousand. Enough plutonium was available for a fourth bomb, but it remained unused when the Japanese Empire surrendered on August 14, 1945.

25

Just before the blast at Alamogordo, some of the participating scientists feared the chain reaction would persist uncontrollably, destroying all of New Mexico if not the entire global atmosphere.

10

. FIRST WAR IN WHICH MORE AMERICAN SOLDIERS DIED FROM COMBAT THAN FROM SICKNESS (DECEMBER 1941–AUGUST 1945)

In the First World War, two doughboys succumbed to ailments for every one killed in action. In the American Civil War, the ratio was closer to four to one. In the American Revolution, nine out of ten military deaths occurred away from the battlefield. And so it went for most soldiers in nearly every conflict in history.

Over the course of the Second World War, a number of momentous innovations changed this pattern, the greatest of which was penicillin. Discovered in 1929, its benefits were not fully evident until 1939, when a team of Oxford biologists noted its peculiar ability to destroy internal bacteria yet not harm human tissue. After the British perfected a stable and concentrated strain, they arranged for American companies to mass-produce it, and the age of antibiotics was born. Used sparingly in the North African theater in 1943, penicillin became widely available to Allied soldiers (mostly American and British) in 1944. The Axis never created an equivalent, save for a much weaker medicine called Prontosil made by the German consortium I. G. Farben.

26

Also late in the war, the Allies achieved major victories against disease-carrying insects. To stave off malaria, troops stationed in the mosquito-infested South Pacific consumed newly synthesized quinine (a bitter yellow powder called Atabrine), while their Japanese counterparts often went without such preventive medicines. Consequently, malaria alone reduced many Imperial fighting units by a third or more.

Ground troops everywhere were subject to typhus, compliments of gnawing little fleas, lice, mites, and ticks. Allied soldiers fought these biting bugs with liberal applications of DDT, an insecticide called “the atomic bomb of the insect world” before it was discovered to be nearly as caustic against animals.

27

Armed with better hygienic training, better food, cleaner water, and more extensive medical care than their opponents, American servicemen finally stood a fighting chance against life-threatening illness.

28

In the American Civil War, Union infantry had one medic per five hundred men. In World War II, U.S. infantry had one medic per forty men.

BEST MILITARY COMMANDERS

Nazi Germany had seventeen field marshals, thirty-six full generals, and three thousand additional generals and admirals. More than twenty-four hundred star-shouldered officers served in the U.S. armed forces. By the end of the war, the Soviet Union had enough dead generals to fill a battalion and enough live ones to fill a brigade.

Ranking these commanders depends on criteria. For level of commitment, few can match U.S. Army air chief Henry “Hap” Arnold, who suffered three heart attacks during the war yet refused to retire. On field tactics, there was the flashy I

RWIN

R

OMMEL

. U.S. Adm. Raymond Spruance had a freakish gift of knowing when to attack and when to hold back. Despite a selfish, divisive ego, Douglas MacArthur boosted morale on the home front like no other.

The wisest among them all realized that no man was an island, that success depended on a multitude of people, from politicians and spies to mechanics and merchant marines. Following are the best commanders based on their respective achievements in directing support through logistics, morale, communications, and overall strategy. Most of all, they are measured by the magnitude of their contribution to the success of their side.

1

. GEORGI ZHUKOV (USSR, 1896–1974)

He was considered by some to be cruel, egocentric, and brutal. Others suggested he was lucky, that his victories came from timely winter storms and enemy hesitation. Still others believed him to be unmatched in his will to win. All charges were true.

Georgi Zhukov was in his midforties when war erupted. Profane and blunt, he often took full credit for ideas not totally his own, demoted officers with impunity, and threatened dissenters with firing squads. Yet he told people how to fight, inspired them to use every weapon, resource, and moment at their disposal, and allowed subordinates latitude in carrying out orders. He was one of the few generals who could stand up to Stalin, and he slowly convinced the dictator to let the generals run the front. Last but not least, no commander from any country ever approached Zhukov’s phenomenal record in the war.