The History Buff's Guide to World War II (33 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

In contrast, the British army traveled by fuel oil rather than fodder, thus becoming the first modern army. Regardless of its reputation for conservatism, rigid class structure, and resistance to change, Britain’s military was often a vanguard of innovation. Colonial troops used machine guns in the Zulu Wars (1871, 1879). The Royal Navy was among the first to switch from coal to oil engines (1913). The RAF was the first independent air force ever created (1918). Much of these adoptions came from a long-standing realization that Britain attained and maintained its vast empire by virtue of superior technology.

4

Horses used in the successful British invasion of Germany: 0.

Horses used in the failed German invasion of the Soviet Union: 625,000.

2

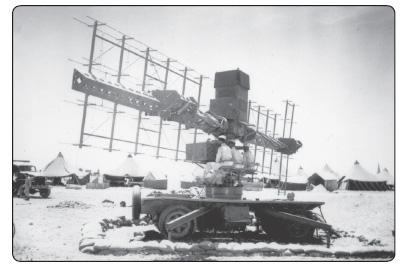

. FIRST USE OF RADAR IN WARTIME (SEPTEMBER 1939)

Owing to the static nature of trench warfare, finding an enemy during World War I was hardly a challenge. Tracking one’s opponent during World War II, however, was like trying to find a fast, mobile, deadly needle in a haystack.

Enter radar, or “Radio Detection and Ranging.” Years before the outbreak of hostilities, private and governmental agencies in Britain, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United States experimented with radio signals and echoes, mostly for tracking airplanes. Results were limited. Once the war started, radar technology progressed rapidly, especially in the United Kingdom and Nazi Germany. The British perfected a network of coastal stations that helped direct the RAF’s meager fighter reserve with maximum effect in the B

ATTLE OF

B

RITAIN

. Germany answered with a guidance system for bombers, using intersecting radar beams to indicate bomb targets. The British quickly learned how to jam these signals, which the Germans then overcame by using variable frequencies.

5

Britain then introduced an improvement the Axis never matched. In 1940, two scientists from Birmingham University successfully tested the cavity magnetron, a transmitter that reduced radio waves from several feet to a few inches, increasing radar accuracy tenfold.

At the dawn of the information age, superior radar technology enabled the Allies to gain an unassailable edge over the Axis.

Of all the sought-after “superweapons,” the cavity magnetron–equipped radar deserved the title. By 1943 the microwave system found its way onto Commonwealth and U.S. bombers, fighters, antiaircraft batteries, ships, and early warning stations. Impressively sensitive (it could detect a submarine periscope) and difficult to detect or jam, the new device enabled the Allies to “see” faster, farther, and more precisely than their opponents ever could. Virtual command of the sea and sky followed. In January 1944 Hitler cursed this leap in radar technology as the worst blow to his plans for victory.

6

After receiving cavity magnetron radars in 1943, Allied destroyers and planes sank three times more U-boats than in the previous year.

3

. FIRST PEACETIME DRAFT IN U.S. HISTORY (SEPTEMBER 1940)

It took the Civil War to instigate military conscription in the United States and World War I to temporarily resurrect it. Yet Americans universally disdained the draft. Even after Japan invaded China and Germany swept through Poland, national opposition to conscription remained steadfast.

In March 1940, more than 96 percent of Americans opposed the idea of declaring war against the Axis. Yet when Hitler conquered Denmark in a single April day and proceeded to take Norway, France, Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg in a matter weeks, attitudes began to shift. By June 65 percent of the American population believed that if Britain fell, the United States would be next. A sense of urgency erupted, since the United States possessed only the eighteenth-largest army in the world.

7

Initial calls for a draft did not come from the White House or the military but from congressmen and grass-roots organizations. Even isolationists such as aviator Charles Lindbergh demanded a heightened state of readiness. Senator Ted Bilbo of Mississippi summed up their convictions bluntly: “We are not going to send our boys to Europe to fight another European war, but we are going to get ready for the ‘Big Boy’ Hitler and ‘Spaghetti Mussolini’ if they undertake to invade our shores.”

8

In June 1940, two days before France fell, a bill was proposed in Congress that all male citizens between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-six should register for possible conscription. Draftees, chosen by lottery, would train in the military for one year and remain on active reserve for a decade. On September 16, 1940, after months of bitter public debate and national introspection, the measure became law.

While Japan carved into China, Italy invaded Egypt, and the Luftwaffe bombed London, millions of American men registered under the Selective Service Act. Just six weeks later the War Department started drawing numbers. Eventually ten million draftees served in uniform, and despite promises to the contrary from senators, congressmen, and the president, half were sent overseas.

9

World War II restarted the draft. Another war helped stop it. Following the unpopular and ultimately unsuccessful police action in Vietnam, President Richard M. Nixon ceased national conscription in 1973.

4

. FIRST U.S. PRESIDENT ELECTED TO MORE THAN TWO TERMS (1932, 1936, 1940, 1944)

Months before the 1940 presidential contest, Franklin Roosevelt assumed he would follow George Washington’s example and resign after two terms. Unfortunately for his Democratic Party, there appeared to be no viable replacement, and Roosevelt reluctantly chose to break precedent and run again.

To oppose him, the Republicans owned even fewer prospects. They eventually placed their hopes on a political rookie, Indiana businessman Wendell Willkie. The Grand Old Party’s nominee had much in common with the president, as he too was well educated, tall, handsome, and exceedingly charismatic. Although he was selected by the GOP, Willkie was a lifelong Democrat.

In spite of growing international unrest, domestic issues dominated the campaign. Willkie agreed with most of FDR’s foreign policy, condemning totalitarianism and pledging to keep America out of war. Willkie instead attacked the bureaucratic beast of the New Deal, labeling such big-government programs as inefficient and ineffective against a stagnant economy. Republicans also condemned Roosevelt’s pursuit of a third term, calling it an act of hubris, if not dictatorship. Roosevelt triumphed nonetheless, bolstered by huge victory margins from key voting blocks, namely farmers, organized labor, and women. He also won a majority of votes from African Americans, who had traditionally sided with Republicans since the days of Lincoln.

10

In 1944, Roosevelt’s health began to fail, yet he rallied enough to convince the public that his sixty-two-year-old body could withstand another election, especially against the Republican’s nominee, brilliant but smug forty-two-year-old Thomas Dewey of New York. Two key factors aided Roosevelt. He dumped his liberal and pro-Soviet vice president, Henry Wallace, for moderate, unknown Harry Truman, and he could point to the recent invasion of Normandy as proof that the long and horrid war was finally nearing an end. Roosevelt won again, though in his four elections, the fourth was his narrowest margin of victory.

11

Wary of another era of one-man domination, in 1951, Congress passed the Twenty-Second Amendment, setting a two-term limit on the presidency. Years later, ardent supporters of fortieth president Ronald Reagan unsuccessfully lobbied for its repeal.

5

. FIRST CARRIER BATTLE (MAY 1942)

In the spring of 1942 a Japanese fleet of three carriers and a complement of supporting cruisers, destroyers, and transports headed southeast around New Guinea and into the Coral Sea. Their mission was to capture key ports and installations in the area, setting the groundwork for an intended attack on Australia.

After intercepting transmissions of the Japanese plan, U.S. naval forces closed in, strengthened by the carriers

Lexington

and

Yorktown

. On May 7, aircraft from the U.S. carriers struck and sank

Shoho

, the smallest of the three Japanese flattops. The following morning and almost simultaneously, a swarm of planes from both fleets found their targets. Bombs and torpedoes fell in scores. Japan’s carrier

Zuikaku

escaped unscathed, protected by the veil of a storm. The

Shokaku

and

Yorktown

each took several bombs but remained afloat. The

Lexington

did not survive, gutted by torpedoes on its port side and set ablaze by three direct bomb strikes. By early afternoon, the contest ceased by mutual withdrawal. Both sides claimed victory, although Japan failed to gain the ports it sought, and the great Imperial assault on Australia never came to pass.

12

The flight deck of the carrier

Lexington

is strewn with debris from an attack. Too damaged after the battle,

Lexington

was scuttled—the first U.S. carrier to be lost in the war.

The battle of the Coral Sea provided a host of maiden events: the first encounter of Japanese and U.S. naval airmen, the first sinking of Japanese and U.S. carriers, and the first time in the war Japan’s navy failed to achieve an objective. But this brief clash in an otherwise placid corner of the globe was nothing short of a revelation, a harbinger of things to come.

13

For the first time in three thousand years of naval warfare, a sea battle transpired completely by air. Not once did enemy ships come within sight of each other. No deck guns ever hit their opposition. From that point onward, ruling the waves required control of the skies.

14

Flying back from a mission on the night of May 7, a Japanese pilot from the

Zuikaku

spotted a flattop and attempted to land, only to be shot out of the sky. Having lost his way in the darkness, he had accidentally tried to set down on the deck of the

Yorktown.

6

. FIRST OPERATIONAL JET AIRCRAFT (JULY 1942)

In the fight for air supremacy, speed was critical. Designers tinkered with engine types, fuel mixtures, wing shapes, prop design, and weight reduction to squeeze more velocity from their aircraft. But physics limited propeller planes to just over 400 mph. After British aeronautical genius Frank Whittle produced the first jet engine in 1937, engineers hypothesized this new propulsion system could reach 500 mph and more. The main problem involved getting a jet engine and an airframe to work in concert.

In this pursuit, German engineers caught and passed the British, developing a working prototype in August 1939: the Heinkel 178. Yet neither the He-178 nor British prototypes could surpass the speed and performance of existing prop-engine fighters. Then, after three years of development, the sleek twin-engine Messerschmitt 262 flew on July 18, 1942, nearing 100 mph faster than anything aloft.

15

Despite its initial success, the Me-262 would not see combat for another two years. The German jet suffered from the same problems afflicting American, British, and Japanese programs: poor engine reliability, shortage of engineers, and lack of precious metals.