The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (72 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

He insisted that, as the young king’s nearest male relative, he should be awarded the care and control of Otto III. This was in fact legal. Otto III’s mother was in Italy, where her husband had died, so the little boy’s temporary guardian, the unsuspicious archbishop of Cologne, handed the toddler over.

13

At once Henry took the child south into Saxony, where his supporters were gathered. While little Otto was kept in safe seclusion, Henry’s cronies began to address him as king and lord; when Easter came, they serenaded him with

laudes

, the formal songs of praise sung to a monarch.

14

The other noblemen of Germany, unimpressed, insisted that Otto would have to give consent before Henry could call himself king. As Otto was not yet speaking, consent was not exactly easy to determine. Henry suggested that, as guardian, he could speak for Otto and give himself permission to become king, but this proposal was rejected as well.

It soon became clear to Henry that if he wanted to become king, he would have to fight for it—and he doubted that he had the strength to resist not just the opposing noblemen in Germany, but also the king of Western Francia, Lothair IV, who had declared himself on Otto’s side in the debate. Instead, he agreed to negotiate a compromise. He would again be given the duchy of Bavaria, which Otto II had taken away; and in exchange he would hand little Otto back to his mother, who became his regent.

15

With the transfer, Otto III again became king of Germany. The hereditary transfer of power had not been clean, but it had partially succeeded.

To the west, though, the hereditary movement of power from one generation to the next suddenly failed. Lothair IV of Western Francia, who had been prepared to fight in defense of Otto III’s claim to kingship, died in 986. He left his own crown to his son Louis the Sluggard. The name, like Henry’s, points to a difficult personality. Louis the Sluggard kept the throne for a single year before he died—in all likelihood, poisoned by his own exasperated mother.

The dukes of Western Francia, like the dukes of Germany, now insisted on taking their traditional role in the election of a ruler. The king’s family had not done an impressive job of ruling in generations, and the dukes rejected the idea of finding a distant blood relation to elevate. Instead, they crowned a king from a new family: Hugh Capet, son of the count of Paris, one of their own. The Carolingian dynasty had finally ended in the west; Charles the Great’s blood kin no longer sat on the throne.

As the first king of a new dynasty—the Capetians—Hugh Capet ruled an old Frankish kingdom that had lost its eastern expanse to Germany, and the southeastern and northwestern territories of Burgundy and Normandy to independence. The lands that remained under the crown were engulfed by multiple currencies, a slew of languages, and a mass of independent-minded Frankish nobles. Hugh Capet had to rule carefully: he had been elected by those noblemen with the tacit understanding that he would not act as a despot. He made Paris his home city, the center of his government, and began in a very gingerly manner to try to pull Western Francia together into a slightly more coherent country.

But his shaky authority was unable to bring peace to his country. Private warfare between French dukes, private oppression of farmers by aristocrats, armed spats between men of different loyalties and languages, dishonest trade, altered weights: Francia was a sea of chaos from border to border. The nightmarish conditions forced the rich to hire personal armies to keep their possessions safe. The poor had no such luxury; instead, they offered to serve their wealthier neighbors in exchange for protection. This became the root of the later practice of feudalism: the exchange of service, on the part of the poor, for protection and provision from the rich.

16

In 989, Christian priests gathered at the Benedictine abbey of Charroux, in the center of the Frankish land, and took the problem into their own hands. For Francia to survive, someone had to quench the flames of private war that had followed the disintegration of Frankish royal power. The priests had no army, no money, and no political power, but they had the authority to declare the gates of heaven shut.

Now they began to wield it. Noncombatants—peasants and clergy, families and farmers—should be immune from ravages of battle, they announced. No matter whose army he fought for, private or royal, Frankish or foreign, any soldier who robbed a church would be excommunicated. Any soldier who stole livestock from the poor would be excommunicated. Anyone who attacked a priest would be excommunicated, as long as the priest wasn’t carrying a sword or wearing armor; the decrees at Charroux recognized the potential overlap between priest and soldier, and were careful to avoid giving armed clergymen a free pass.

17

The synod at Charroux—the first step in a gathering movement known as the Peace and Truce of God—was the first organized attempt by the Christian church to lay out an official policy on the difference between combatants and noncombatants in war. It took another tentative step forward in 994, when the pope announced that the Abbey of Cluny, in the eastern Frankish lands, would become a place of refuge. When the abbey had been established around 930 as a private monastery, its founder, William the Pious of Aquitaine, had written into its charter a remarkable degree of independence. Cluny, unlike other private monasteries, was placed directly under the supervision of the pope. No secular nobleman—not even the founder or his family—had the right to interfere in its government. Cluny (theoretically) answered to no political sovereign. Nor was it under the authority of any local bishop. So, as a place of refuge, it could offer safety to anyone who made it to the abbey’s walls, no matter how unpopular the refugee was. Cluny itself was protected, by threat of excommunication, from being invaded, sacked, or burned.

18

The Peace of God movement was more than an attempt to sort out the ethics of war. It was a desperate response to a world in which the possibility of salvation and the mission of the Christian church were increasingly tied to the territorial ambitions of particular kings. The setting of Cluny as a place of refuge gave the pope—the man who was supposed to have inherited St. Peter’s power to open and close the gates of heaven—ultimate authority to grant safety during time of war.

But it was an imperfect solution.

Just how imperfect became clear in 996, when Otto III of Germany reached the age of sixteen. The nobles of Italy agreed to recognize him as king of the land that had once been northern Lombard Italy, and now was simply the Italian Kingdom, part of the peninsula but not all of it, an appendage of the German realm. With the kingship of Italy in his hands, Otto III immediately appointed his twenty-four-year-old cousin to be Pope Gregory V, the first German pope. At once the new pope returned the compliment by crowning him “Holy Roman Emperor,” Protector of the Church and ruler of the old Roman lands.

The symbiotic relationship between pope and emperor strengthened both; it was a return to the days of Otto’s grandfather, when the circle of power had first been created. But the return dealt a serious blow to the idealism of the Peace of God. The church could only offer peace and refuge during time of war as long as it remained free from the state; refuge could only be found in a place whose leaders had nothing to gain, or lose, from the king.

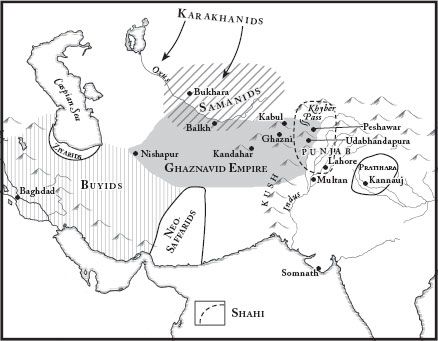

Between 963 and 1044, Alp Tigin establishes the Ghaznavid empire by conquering the enemies of Islam, the Turks establish a kingdom by conquering the Ghaznavids, and the Chola dominate the south of India in the name of Shiva

T

HE

I

SLAMIC LANDS

had fractured again and again. One caliph ruled in Cordoba, another in North Africa; the third caliph, of Abbasid blood, sat in Baghdad under the complete control of the Buyid clan. The Samanids ruled in the east, the neo-Saffarids in the south, and the Hamdanids near the coast of the Mediterranean. South of the Caspian Sea, the Ziyarid dynasty ruled over a little kingdom that had turned away from Islam and back to the old Zoroastrianism of the disappeared Persian empire.

And then there were the Turks: men descended from the once nomadic tribes of the northeast who had come down into the Islamic kingdoms as slaves and soldiers, and who had risen slowly to claim greater and greater influence there. They had no titles, but they had strength.

In 963, one of these Turks took the final step towards kingship. Alp Tigin had once been a stalwart general for the Samanid emir, chief commander of the Samanid armies. However, he had fallen out of favor the year before, when the Samanid emir died. Instead of supporting the emir’s closest blood relation (his brother Mansur), Alp Tigin tried to force the election of his own son to the Samanid throne.

1

This indirect bid for power failed, and Alp Tigin left the Samanid capital just ahead of Mansur’s hit men, heading east. He arrived at the city of Ghazni, southwest from the Khyber Pass, and conquered it. There he ruled as king, over a much tinier empire: the breadth of one city.

In 975, Alp Tigin died. His son-in-law Sebuk Tigin and his son Abu-Ishaq took control of the town together. Of the two, Sebuk Tigin proved the cannier politician. Alp Tigin had been content to rule as an outlaw king, but Sebuk Tigin had ambitions to build a real, legitimate empire. He convinced Abu-Ishaq to travel west with him to the court of Mansur, king of the Samanids, Alp Tigin’s old enemy. There, they negotiated a tricky peace. They swore loyalty to Mansur, in return for recognition: Mansur agreed to make Abu-Ishaq the legitimate governor of Ghazni and to appoint Sebuk Tigin to the position should Abu-Ishaq die.

It is not entirely surprising that Abu-Ishaq promptly died, leaving Sebuk Tigin as the Samanid-approved governor of Ghazni. Almost at once, Sebuk Tigin attacked and captured Kandahar, which for a short time had been in the hands of the neo-Saffarid dynasty of the south. He was still swearing loyalty to the Samanids, but now he was more than just a city governor; he ruled a territory that would slowly develop into a kingdom in its own right. This development worried the Samanids, but they had troubles of their own. Northern Turkish nomads known as the Karakhanids had begun to cross the Oxus river south into Samanid land, raiding the silver mines on which the Samanids relied. The Samanid army, busy fighting for its silver, didn’t have energy to spare for Sebuk Tigin.

But his expansion did not go unnoticed. At the capture of Kandahar, the nearest Indian king, Jayapala of the Shahi, began to prepare an attack.

The Shahi kingdom, which controlled the Khyber Pass, had once been a Buddhist kingdom with Kabul as its capital; but Kabul had fallen into Muslim hands three hundred years earlier, and the Buddhist kings had been driven from the throne a century before by a Hindu ruling line. The Hindu king Jayapala, who now ruled from the city of Udabhandapura, launched several unsuccessful assaults against Ghazni. In retaliation, Sebuk Tigin attacked the western border of the Shahi and took some of Jayapala’s territory away. Jayapala was forced to move his capital once more, this time to the city of Lahore. But although he shifted the center of his government to Lahore, he remained in Udabhandapura, now the dangerous frontier of his country.

2

The Samanids continued to be distracted, both by the raids from the north and by the increasing power of the Buyids to their west. Sebuk Tigin fought on. He captured Kabul; he battled his way steadily east into Shahi land; and by 986 it had become clear to Jayapala that an all-out war was on his hands. “Observing the immeasurable fractures and losses every moment caused in his states,” says the sixteenth-century Arab history

Tabaqat-i-Akbari

, “and becoming disturbed and inconsolable, he saw no remedy except…to take up arms.”

3

He assembled an enormous army—perhaps as many as a hundred thousand men—and marched northeast to confront Sebuk Tigin near Kabul. “They came together on the frontiers of each state,” the

Tabaqat-i-Akbari

tells us. “Each army mutually attacked the other, and they fought and resisted in every way until the face of the earth was stained red with the blood of the slain, and the lions and warriors of both armies were worn out and reduced to despair.”

4

The battle was not a clear victory for either side, but Jayapala was the first to draw back. Sebuk Tigin’s men were motivated not merely by the joys of conquest but also by religious fervor in a way foreign to the Hindu soldiers who opposed them. Sebuk Tigin’s battles against his Muslim counterparts had been motivated by sheer ambition, but in northern India he could exhort his men with a more worthy battle cry. “He made war upon the country of Hindustan,” writes the contemporary Arab chronicler al-Utbi, “whose inhabitants are universally enemies of Islam, and worshippers of images and idols. He extinguished, by the water of his sword-wounds, the sparks of idolatry…. He undertook the hardship of that sacred war and displayed unshaken resolution in patiently prosecuting it.”

5

In the face of this holy enthusiasm, Jayapala sued for peace, paid his enemy tribute, and withdrew. But he was really regathering his forces. “Unless he set his face to resist,” al-Utbi writes, “his hereditary kingdom would go to the winds.” As soon as he had managed to collect another army from among his tributaries and allies, Jayapala reneged on the deal and marched on his enemy again.

72.1: The Khyber Pass.

Credit: Roger Wood/CORBIS

72.1: Expansion of the Ghaznavids

Again he was defeated, this time just west of the Khyber Pass. Sebuk Tigin, vexed by Jayapala’s breaking of his oath, seized the Khyber Pass for his own. He now owned the highway into northern India, and he “proceeded to the country of the infidel traitor, plundered and sacked the country, dug up and burnt down its buildings, carrying away their children and cattle as booty.” In the face of the sacking and burning, Jayapala retreated to the east, his kingdom contracting still further.

6

Sebuk Tigin died in 997, ruler of a realm that had expanded well into the Kush mountains: the Ghaznavid empire. After a sharp and very brief civil war, his oldest son Mahmud claimed the throne.

Mahmud’s first great conquest was not in the north of India, but over on the western flank of his realm. The Turkish Karakhanids had now been harassing the Samanids for more than twenty years. In 992, they had rushed so far into Samanid territory that they were able to capture the capital, Bukhara; but when their chief died unexpectedly, they withdrew and gave the city up. Now, led by their new chief Nasr Khan, they again pushed all the way to Bukhara and sacked it. This time they kept the city. The young Samanid emir withdrew to the south of the Oxus river. The Karakhanids seized the territory around Bukhara for their own, while Mahmud—now the strongest ruler in those parts—claimed the rest of the Samanid land north of the Oxus for the Ghaznavids.

The strongest opponent of Ghaznavid power was now Jayapala, and Mahmud made an oath: he would invade India every year until the northern lands were his. On November 27, 1001, Mahmud Ghazni met Jayapala and his army just on the other side of the Khyber Pass, near Peshawar. Once again, the hard-fought battle damaged both armies: “Swords flashed like lightning amid the blackness of clouds,” writes al-Utbi, “and fountains of blood flowed like the fall of setting stars.”

7

Jayapala lost heart. He had been defeated again and again, each time backing slowly away from his enemy, and he was humiliated and sinking into despair. Not long after the battle at Peshawar, he built himself a funeral pyre, entered it, and set it on fire.

8

His son Anandapala took up the resistance. Like his father, he fought hard against the persistent invaders, and Mahmud’s advance into the Indus delta was a slow progression of two steps forward and one step back. But mile by laborious mile, he moved deeper and deeper into lands that had once been Shahi. By 1006, after five years of bloody fighting, he had made his way into the upper lands of the delta. By 1009, he controlled most of the Punjab. Around 1015, Jayapala’s son Anandapala, the last Shahi king, was driven completely from his lands and disappeared into exile.

The list of conquests dragged on. In 1018, Mahmud even made an advance to the walls of Kannauj itself, where he slaughtered the remnants of the Pratihara army and drove the Pratihara king out of his capital. As he moved farther east, his fast, mobile cavalry proved impossible for the slower armies of foot-soldiers and elephants to resist.

9

His devastation had now enveloped most of India’s northwestern quarter. He circled around the outside of the territory he had laid waste, and in 1025 reached the height of his conquests in India: he arrived at the harbor town of Somnath, on the western coast, where one of the most sacred images of Shiva stood, and where hundreds of thousands of pilgrims travelled to pay devotion to the god.

The Ghaznavid armies slaughtered thousands of pilgrims and sacked the temple of Shiva. Mahmud himself toppled the image, pulverized the head and shoulders, and ordered the rest taken back to Ghazni. There, he placed it at the foot of the steps into the mosque, so that Muslim worshippers could wipe their feet on it as they entered. His entire life had been spent in victorious empire-building; now, at the end, he could boast that those victories were the triumph of his God over the gods of his enemies.

10

Five years later, Mahmud died of a malarial fever, at age sixty-three. His empire had already reached its high point. The fracturing of the Muslim east into separate kingdoms allowed for the sudden mushroom-like growth of any realm that was lucky enough to be led by an energetic and long-lived general, but the kingdoms that grew so suddenly into empires were equally likely to shrink. Mahmud had spent thirty-three years conquering his way into India, but another kingdom was already beginning to swell on the western border of the Ghaznavids, led by a warrior named Togrul.

The unruly Karakhanid attacks had gained the Turkish nomads a little land of their own, and in 1016 the young chief Togrul had inherited the command of his own particular tribe. This did not give him much authority with the others. The Turks had absolutely no respect for an overlord, something that had shocked the Muslim traveller Ibn Fadlan; journeying through Turkish lands some decades before, Ibn Fadlan had earned the friendship of one powerful Turkish chief and had assumed that the alliance would protect him. Running into another Turkish chieftain on the plains, Ibn Fadlan demanded passage in the name of the Turkish khan. The nomad laughed at him: “Who is the khan?” he said. “I shit on his beard.”

11

But the tribes near the Oxus had land of their own, and they were surrounded by the rule of Muslim empires; they had begun to absorb the new standards of a settled people. Togrul, as driven as the great Ghaznavid ruler Mahmud, took command of his tribe and began to conquer. While Mahmud was building his empire in northern India, Togrul was building a realm of his own around the Oxus. And after Mahmud’s death, Togrul began to fight his way through the western Ghaznavid land. By 1038, he had reached the Ghaznavid capital of Nishapur and claimed it as his own. He had himself crowned there as sultan of the Turks, overlord of his tribes.

Which was not entirely true. Other Turkish chiefs were also on the move, and they did not yet recognize the overlordship of Togrul’s dynasty. But Togrul was certainly the most victorious of the Turkish chiefs so far, and his conquest of the Ghaznavid lands to the west had given him the largest Turkish realm. By 1044, Togrul’s Turks controlled most of the lands west of the mountains; and the Ghaznavid empire, which had begun as a Muslim dynasty in the Muslim lands, now existed only as a northern Indian kingdom.