The Incredible Human Journey (40 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

So that means that the Neanderthals – whether or not rare liaisons led to hybrids whose existence has now been expunged from

the modern gene pool – really did disappear. But why did the Neanderthals, who had been living in Europe for hundreds of thousands

of years, fade away when modern humans arrived on the scene?

I needed to look more closely at the archaeological evidence: was there any difference in the way modern humans and Neanderthals

were subsisting in their environment? Was there anything that could have given modern humans ‘the edge’ in Europe?

Treasures of the Swabian Aurignacian: Vogelherd, Germany

In a complete contrast to the ultra-modern Institute in Leipzig, I next visited the medieval university town of Tübingen.

I walked up cobbled roads to a castle where I passed through a great arch into a courtyard, then on past a fountain and up

stone steps, then turned a corner to enter the Department of Early Prehistory and Quaternary Ecology. At the end of a corridor

plastered with posters of wonderful carved animals and birds, I found Professor Nick Conard in his office.

Nick’s office was lined with red cupboards on one side, dark wooden bookshelves on another, and wooden filing cabinets. There

were two desks, each piled high with papers and books, and in one corner was a large grey safe with a map of the Swabian Jura

hanging on it. Nick had spent years excavating sites around Tübingen, where he had discovered evidence of the earliest modern

humans in Europe. But it wasn’t just stone tools that he’d found: there had been some rather wonderful pieces of art and

musical instruments. And he had some of them in the safe. I had to look away while he found the key and then started bringing

small cardboard boxes over to a low table, where we sat down to open the boxes of treasures.

The first object Nick took out, dating to around 35,000 years ago, was an ivory flute. It was discovered in 2004, at a cave

site called Vogelherd, lying beneath two other flutes that had been made from hollow swan bones. The ivory flute had taken

much more craftsmanship, though: it had been carved out of a mammoth tusk, then split to hollow out the inside, and joined

back together with something like birch pitch. There was a row of incised notches down each side, crossing the join, perhaps

made to help when putting the two halves back together.

The ivory flute had been smashed up into fragments, which archaeologists had found and carefully pieced back together; the

notches had also helped the archaeologists when it came to reconstructing the flute. Nick explained that, using mammoth ivory,

the instrument-maker wouldn’t have been constrained by the dimensions of a hollow bird bone and so could make a much larger,

longer instrument. But it also seemed to be an exhibition instrument – designed to show off the technical skill of the instrument-maker.

Nick had been completely taken by surprise by this discovery. They had found mammoth ivory carvings in Vogelherd before, but

this was the first indication of music that had emerged from the site. The three small flutes represented the first real evidence

of music – anywhere in the world. Nick had a replica of one of the swan-bone flutes, which I tried to play with less than

impressive results, not being any sort of musician. But I could at least get a series of notes out of it. More accomplished

musicians have tried and produced music that sounds quite harmonious to the modern ear, with tones comparable to modern flutes

or whistles.

Opening the other boxes, Nick brought out some finds from the 2006 digging season at Vogelherd, and from the nearby cave of

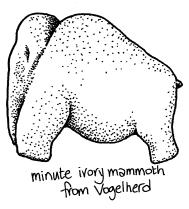

Hohle Fels – beautiful things nestled into cut-to-fit shapes in foam inside each box. Nick lifted out a tiny ivory mammoth, just 3cm long. It was carved in the round, with naturalistic detail, its trunk hanging

down and curving over to the right, and there was a tiny spike of a tail. The hind legs were shorter than the front. It seemed

perfectly proportioned. The bottom surfaces of the feet were scratched in a crisscross pattern.

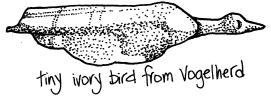

Then there was a lion carved in relief, again in ivory, with hatching along its back. It had a long body, and its hackles

were raised. And a tiny, beautiful bird. The body of the bird had been discovered in earlier digs, and there had been much

speculation about it. Was it a human torso?

But then the archaeologists had discovered the head and neck – a minute fragment that could so easily have been passed over.

But it fitted the body, and, suddenly, there was a bird, perhaps a duck or a cormorant, with its neck outstretched. Finally,

from another small box, Nick carefully lifted out a minute lion-man. Standing just over 2cm tall, he looked like a miniature

version of the famous lion-man from Hohlenstein-Stadel, near Ulm – around the corner from Hohle Fels. All of these objects

dated to more than 30,000 years ago.

1

But there was one more surprise. Nick opened a long box, and inside it was a long, smooth piece of stone, unmistakably carved

into the shape of a penis, with the foreskin and glans carved into it at one end. We contemplated this bizarre object. Was it a hammer stone, carved in a phallic shape as a joke? Or could it be that this

stone had a functional use more related to its shape? Nick was quietly amused by the find. It suggested that the people of

the Swabian Aurignacian had, at the very least, a healthy sense of humour, and perhaps an even healthier sexual appetite.

The art of the Swabian Jura was fascinating, and this really is the earliest evidence of something that we can properly appreciate

as art. I had seen pierced shells and ochre ‘crayons’, leaving us guessing what was drawn with them, but here were carefully

executed carvings of animals, and strange therianthropic beasts – men with heads of lions. Nick said that the styles of these

Aurignacian carvings were similar across different sites in the Swabian Jura, although there were many different themes. It

seemed to be a time of some artistic experimentation. But recurring imagery like the lion-men from Hohlenstein-Stadel and

Hohle Fels also suggested very strongly that they were made by people from the same cultural group in the Lone Valley. Many

different ideas have been put forward about the meaning and function of these artefacts: some have suggested that they indicate

hunting magic, and the therianthropic figures in particular have been linked to shamanism. For Nick, the discovery of the tiny waterfowl carving challenged previous interpretations of Aurignacian carvings from the

Swabian Jura as representing fast and dangerous animals, with whom Palaeolithic hunters may have identified.

1

‘I think the combination of these symbolic artefacts, ornaments, figurative representations and musical instruments, shows

us these people have the mental sophistication of ourselves, the same creativity that we have,’ he said. ‘And we can even

get insights into the system of beliefs. For instance, the examples of human depictions combined with lion features show that, at least in their iconography, they

were engaging in transformation: people having a connection with the animal world, being depicted as mixed animal/human figures.’

But how could these small ivory carvings hold any clue to the survival of modern humans – and the demise of the Neanderthals?

Well, certainly the Neanderthals, however intelligent and whether or not they had language like us, never produced anything

like the objects found at Vogelherd. I asked Nick about the differences between modern humans and Neanderthals, and it became

clear that he thought culture had played a key role in the expansion of modern human, and contraction of Neanderthal, populations,

during the late Pleistocene.

On their own in Europe, the Neanderthals seemed to have been getting along just fine.

‘The Neanderthals were the indigenous people of the area. They had very sophisticated technology, certainly command of fire,

and knew how to get along in their environment. They had everything 100 per cent under control, and they were doing very well,’

said Nick.

‘So if they were so good at surviving in Ice Age Europe, why did they disappear?’ I countered.

‘Well, I would approach that question from an ecological point of view. If you have one organism occupying a niche, it’s going

to stay there until something drives it out of its niche: either environmental change that makes it impossible to occupy the

area, or another organism coming in and competing for resources.’

‘So you’re saying that modern humans were that competing organism?’

‘Well, yes. It’s very clear that Neanderthals and modern humans were really occupying the same niche. We see that unambiguously

in the archaeological sites: the diet consists of the same foods – especially reindeer, horse, rhinos and mammoth.’

‘But why did we modern humans survive and not Neanderthals?’

‘Well, there’s no question the Neanderthals were very effective hunters, and really were at the top of the food chain. But

we do see some differences in technology. I think that the innovations that modern humans developed in Europe, the Upper Palaeolithic

toolkit, organic artefacts, but also figurative art, ornaments and musical instruments – these are all things that seemed

to help give them an edge against the Neanderthals.’

I found it hard to imagine why art and music might have given modern humans an advantage.

‘Well, think of the lion-man,’ said Nick. ‘There’s a lion-man from this valley, and a lion-man from the Auch Valley. It’s

the same iconography, the same system of beliefs, the same mythical structure, and they’re the same people. And we don’t see

those kinds of symbolic artefacts with Neanderthals, so it seems that their social networks were much smaller than those of

modern humans.

‘And from my point of view,’ he continued, ‘the evidence even at this time, 35,000 years ago, is completely unambiguous: music

was a really key part of human life. It’s not entirely clear how that would give you a major biological advantage over the

Neanderthals, but it seems to fit into this complex of symbolic representation, larger social networks. Perhaps music helped

to form the glue that held these people together.

‘When the competitor arrived, the Neanderthal way of doing things wasn’t as effective in the face of people who had new ways

of doing things, new technology, new culture and social networks,’ explained Nick.

Whereas competition for an ecological niche seemed to have spurred modern humans on to develop wider social networks, the

Neanderthals appeared to be ‘culturally locked in’. It was a competition that modern humans would eventually win. Nick explained

that, while their respective territories probably shifted back and forth over the centuries and millennia, Neanderthals were,

on average, retreating while modern humans expanded.

‘In regions like the Levant, we have good evidence for movement back and forth of the two populations. It’s certainly not

the case that modern humans always immediately expanded at the cost of Neanderthals; there are some good examples of Neanderthals

displacing early modern humans, too.

‘When the new people came in, resources got tight, and modern humans were able to develop new technologies and new solutions

quicker than the Neanderthals. In a sense there was a continual cultural arms race going on. And here, in this setting, it

seems like a lot of innovations took place that gave the modern humans a bit of an edge. But it wasn’t a sudden, blanket devastation of the Neanderthals: there was a lot of give and take, but, ultimately, they were

pinched out demographically.’

‘So do you think modern humans and Neanderthals were actually in contact with each other?’ I asked.

‘Well, in some areas, there were fairly dense populations of Neanderthals. And I think they did meet. And I think they would

have been checking each other out from a distance, often avoiding each other. That was probably the most common scenario,

but there may have been times when they came together, in peaceful co-existence, and times when there was quite a bit of conflict.’

‘What do you think about the question of interbreeding?’