The Incredible Human Journey (35 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

‘In north China, the origin of pottery is thought to be very much related to the development of agriculture,’ explained Fu.

‘But from our study, we think the origin of the pottery in south China is related to boiling snails.’

I was more than a little sceptical about this idea. Certainly, there were plenty of snail shells in Zengpiyan Cave, but there

was no real evidence that they had been deposited there by humans, rather than washed in with the river sediments, or even

that they had been cooked.

But it was time to subject our pot to a test. Most of the early pots were round-bottomed cooking cauldrons, like the hemispherical

pot we had made, and seemed well designed for boiling water. After our pot had cooled, we subjected it to another test: filling

it with water and bringing it to the boil over an open fire. It didn’t break. In fact, there’s no evidence that the Guilin

pots had been heated again after their initial firing, although our experiment had at least demonstrated that they

could

survive being heated.

It may be possible to find out what the pre-Neolithic potters of Guilin were putting in their pots, using residue analysis

– which can be applied to fragments. Until then, any theories about what the pots were used for, including snail-cooking,

must remain speculative. Some archaeologists have argued that the early pre-Neolithic pots were used to cook wild grains,

and although there is no direct evidence for this either the pots are from a time when wild grasses start to form a more important

part of diets.

6

During the LGM, East Asia became colder and drier: deciduous trees retreated south of the Yangtze River and vast areas of

what is now China became grassland. After the Ice Age, the global climate became warmer and wetter, and there was more carbon

dioxide in the atmosphere, which may have resulted in grasses becoming up to 50 per cent more productive. It is around this

time that the archaeological record shows people in China, as well as in south-west Asia and Europe, beginning to focus on

collecting wild grasses.

7

But then, around 11,000 years ago, there was a cold, dry spell, comparable to the Younger Dryas in Europe. Perhaps it was

this deterioration in climate that provoked the foragers to start cultivating grasses – whose seeds could be stored through

the winter.

7

,

8

Although China is now dominated by rice agriculture, millet was just as important to the early cereal growers. Genetic studies

of modern cultivated and wild grasses have suggested that domesticated rice (

Oryza

sativa

) may derive from the Asian wild rices

O. rufipogon

and

O. nivara

. There are two subspecies of domestic rice which may relate to two, separate centres of origin of rice farming: in East

Asia and in South Asia. Foxtail millet (

Setaria italica

) may come from the wild green foxtail (

S.

viridis

), while broomcorn millet may come from a wild grass of the same name:

Panicum miliaceum

. Generation upon generation, selection of more seedy plants made the domesticated varieties more productive than their wild

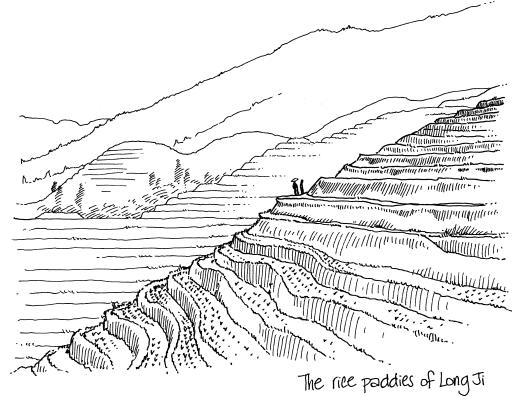

counterparts. I had never really thought of rice as ‘grass’. Then I visited the terraced paddy fields of Long Ji and saw

Liao Jongpu, whose family had farmed there for generations, with a handful of grass-like seedlings, picking out sprigs of

three or four stems at a time, to sow into his submerged fields. It looked like grass, but it was going to be food.

As the climate warmed back up again after 10,000 years, cereal cultivation intensified – and was there to stay. Today, rice

in south China has a higher genetic diversity than that in the north, suggesting that the origins of domestication lay in

the south. But the rice of the Yangtzi Basin, while less genetically diverse,

looks

more ancient and closer to its wild counterpart.

8

Climatic changes and human manipulation of the environment make it really difficult to predict the origins of plant strains

from their modern-day distributions.

7

The earliest archaeological evidence of agriculture in China comes from the area around the Yangtzi River Valley. Grinding

slabs and wild rice husks have been found in Upper Palaeolithic cave and rockshelter sites, dating to beyond 10,000 years

ago, showing that people were collecting and processing wild grasses. It’s important to remember that the grass seeds were just part of a much wider diet: wild rice and millet were

not productive enough to have been a staple food, and would have been just one part of a broad-based subsistence strategy.

And, in fact, although we tend to focus on rice because of its importance today, the earliest domesticated plants may not

have been cereals: they could have been starchy roots and tubers like yams and taro, or even non-food plants like gourds or

jute. The first farmers are likely to have been cultivating a range of crops.

7

In the 1970s, evidence for cultivation started to appear as Neolithic villages were discovered, dating to around 7000 years

ago. Since then, the earliest dates for farming in the region have been pushed back to about 10,000 years ago, and even earlier.

In 2001, archaeologists uncovered a Neolithic site in Shangshan, in Zhejiang Province. The site was the remains of an early

village: post-holes and trenches marked the outlines of dwellings, while stone tools, large grinding stones, pebble pestles

and red pottery provided clues about life in the village. Many of the stone tools were basic chipped pebbles and flakes, just

as are found throughout the Palaeolithic in China, but some are something new and different entirely – stone axes and adzes

– suggesting an increased reliance on cultivation.

These people were working the land.

9

The pottery at Shangshan is still similar to the earlier forms – simple, hand-formed or slab-built pots, fired at low temperatures

– but it also contains important clues to the new way of life in Shangshan village. The clay was tempered with bits of plant – the first example of this – and some of those plant remains are rice husks, shorter

and fatter than wild grains, suggesting these may be the remains of an early domesticated variety. Charcoal embedded in the

pottery has been radiocarbon dated to around 10,000 years ago.

Earlier sites with pottery are caves, like Zengpiyan. But the Neolithic village of Shangshan is in the middle of a river basin.

It represents the beginnings of a new, more sedentary lifestyle. Instead of moving around the landscape, setting up temporary

camps or using natural ‘homes’ like rockshelters and caves, a place was chosen for its suitability for growing crops, and

permanent houses were built.

9

The transition to farming and a settled way of life was gradual and patchy. It is likely that the early cultivators were semi-nomadic

‘collectors’, using wild foods supplemented with cultivated varieties. Caring for crops would have increased productivity

but would also have tied farmers to their fields, so this is perhaps why they stopped being nomads and settled down in villages

like Shangshan. But it is also important not to imagine that hunting and gathering was completely abandoned as agriculturalism

was taken up. Even in recent, historic times, farmers continued to collect wild plants and hunt wild animals.

8

Some archaeologists have suggested that population pressure was a motivating factor in the origin of farming and a settled

way of life. But settlement of large communities doesn’t happen until after 9000 years ago in China. Early settlements are

small-scale and most of the artefacts found in them are the tools of daily use, rather than ‘luxury’ items like beautiful

pots or jewellery. So prehistoric Chinese society between 13,000 and 9000 years ago seems quite egalitarian; the proposition

that agriculture may have arisen there to support a stratified society and accumulation of wealth – or that early pottery

was developed by aggrandising individuals as a sign of prestige – seems unfounded. Although I rather like the idea of ‘competitive

feasting’, there’s no evidence that this drove the origins of agriculture or pottery. Climate seems to have been a major factor,

but the precise environmental and social factors that led to the gradual adoption of agriculturalism and a settled way of

life in the East are still unclear.

8

,

5

The transition to agriculture should not be viewed as inevitable or progressive, but once it originated it spread (although,

in a few areas, including parts of Polynesia, New Zealand and Borneo, farmers faced with unsuitable environments reverted

to foraging).

1

So how did the spread of agriculturalism occur? Did the farmers’ population expand and replace the hunter-gatherers and their

culture, or did the culture of agriculturalism spread among existing populations of foragers? Ammerman and Cavalli-Sforza

proposed a ‘wave-of-advance’ model in Europe, where the farmers’ expansion can be seen as a spreading ripple of intermarriage

and gene dilution, until the populations furthest from the cultural epicentre are genetically almost entirely derived from

the original hunter-gatherers. Thus the population of western Ireland is 99 per cent genetically from the original foragers,

with just 1 per cent of lineages traceable back to Anatolian farmers.

1

Although we don’t yet understand the relationship between genetics and morphology, we can at least assume that people’s faces

reflect their genetic make-up. So are East Asian features an indication that Neolithic farmers spread throughout eastern Asia,

replacing earlier populations, or are those faces from more ancient lineages, before the advent of agriculturalism?

It would be nice to have a range of skulls that showed the emergence of East Asian features and allowed us to date the morphological

changes, but skeletal evidence from the Far East is rare, especially before 11,000 years ago. The Niah skull, at around 40,000

years old, does not look ‘East Asian’, although it does bear similarities to the Ainu, the descendants of the original Jomon

population in Japan. But there is a skull with recognisably East Asian features, from Java, dated to 7000 years ago, and thus

pre-dating the beginning of rice cultivation in Indonesia.

3

Some geneticists have argued that Y chromosome variants suggest that millet and rice farmers did indeed spread out from China,

largely replacing earlier populations throughout East and South-East Asia,

10

but Oppenheimer

3

argues that the balance of the genetic evidence suggests a spread of people, with what we now recognise as

East Asian features, much earlier than the Neolithic – around the LGM. He suggests that, at this time, people would have been

retreating back towards the warmer coastline, populating the expanded coastal plains left by the drop in sea level. Oppenheimer

suggests that, before the LGM, the inhabitants of East Asia looked like the original beachcombers. Then, during the LGM, ‘East

Asian’-looking people from Central Asia moved outwards to the coasts of East Asia.

If Oppenheimer’s theory is right, it would seem that, as in Europe, most of the inhabitants of East Asia today are descended

from the original beachcombers and the coastward-bound populations of the LGM, rather than from a wave of Neolithic farmers

spreading through the region. Culture and language are much more labile, transportable commodities. Our genes betray a much more ancient heritage.

So, even in Shanghai, with all its skyscrapers and technology, the people may look very much like the hunter-gatherers who

inhabited that coastal plain 20,000 years ago.

4. The Wild West:

The Colonisation of Europe

On the Way to Europe: Modern Humans in the Levant and Turkey

Considering that Europe is geographically so close to Africa, it seems remarkable that modern humans made it all the way to

Australia some 20,000 years before we find any evidence of their presence in Europe. Why did it take so long? The answer is likely to be complex, involving geographical and environmental barriers, and, perhaps,

the presence of other humans already occupying Europe. Because, whereas in most of Asia (with the notable exception of Flores)

earlier humans had vanished long before moderns arrived on the scene, Europe was the domain of the Neanderthals.

There is a huge gap between the appearance of the first anatomically modern humans in the Near East – in the Skhul and Qafzeh

caves in Israel, some 90,000–120,000 years ago – and the first evidence of modern humans in Europe – at around 45,000 years

ago. After Skhul and Qafzeh, modern humans disappear from the Levant for around 50,000 years, although it seems that, during

this time, modern humans were making their way eastwards along the coast of the Indian Ocean.

From Arabia and the Indian subcontinent, it may seem that the colonisers should have been able to spread north into Europe

with ease. Stephen Oppenheimer

1

suggests that, just as deserts may have blocked the northern route out of Africa for much of the last

100,000 years, the way from the Indian subcontinent and Arabian Peninsula to the Levant was also sealed off by geographical

barriers: by the Zagros Mountains, and the Syrian and Arabian deserts. While the beachcombers surged eastwards, their northwards

expansion into Europe was blocked. But around 50,000 years ago, the climate warmed up briefly, for a few thousand years. Oppenheimer argues that this warming opened up a green corridor from the Arabian Gulf to Syria, a gate into Europe.

The colonisers could then have spread north-east, skirting the Zagros Mountains, up the coast of what is now Pakistan and

Iran, and up the River Euphrates into modern-day Iraq and Syria, making their way from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean

coast. Some archaeologists argue that Upper Palaeolithic sites along the Zagros Mountains support this route, and indeed suggest

that Upper Palaeolithic technology may have originated around the Zagros Mountains, with some dates in excess of 40,000 years.

2

However, these dates need to be treated with caution: firstly, these are dates at the very extreme of what is considered reliable for radiocarbon dating, and, secondly, the dates

were reported in the 1960s, long before the new sampling and calibration techniques were applied.

However, the types of tools found at the Zagros sites are similar to the earliest Upper Palaeolithic tools found around the

eastern Mediterranean, known as the ‘Levantine Aurignacian’.

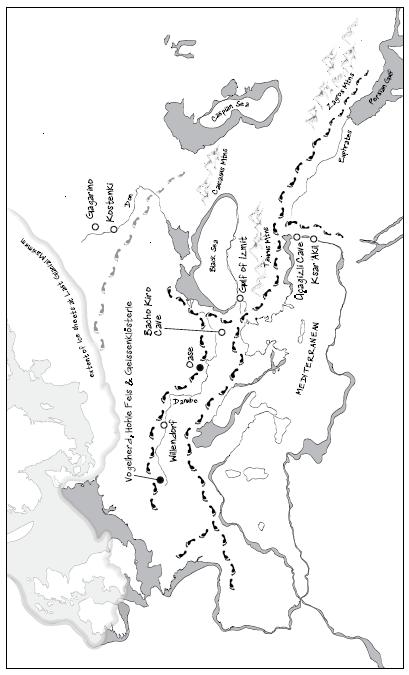

Routes into Europe. The black footprints represent the first modern humans to reach Europe, bringing with them the

Aurignacian culture, starting around 45,000 years ago; the grey footprints represent the later incursion of the Gravettian

people, beginning around 30,000 years ago.

The route from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean, following an earlier southern dispersal from Africa, seems a reasonable

suggestion, but other researchers still favour a simple northern route out of Africa, from Egypt. But whichever of these routes

was taken, we would expect to find part of the archaeological trail in the Levant and in Turkey; in other words, in those

countries that border the eastern Mediterranean.

There is a growing body of archaeological evidence for the earliest modern humans in the Levant and Turkey, in the form of

Upper Palaeolithic stone tools, and ornaments – and some bones.

In the 1940s, archaeologists began to excavate down through 19m of deposits at the site of Ksar ‘Akil, near Beirut in Lebanon.

They found twenty-five layers containing Upper Palaeolithic archaeology. In the deepest layers, they found Levallois-type

technology (stone tools made from prepared cores), typical of the Middle Palaeolithic, alongside classic, reshaped Upper Palaeolithic

tools, like end-scrapers and burins. In later layers, the Levallois cores are replaced by cone-shaped prismatic cores, from

blade manufacture – a hallmark of the Upper Palaeolithic. Dating of layers above and below the earliest Upper Palaeolithic

stratum at Ksar ‘Akil suggests that those tools were being made there somewhere between 43,000 and 50,000 years ago.

3

And the discovery of a skeleton at Ksar ‘Akil confirmed that it was modern humans who were making those tools.

4

Dating of the Upper Palaeolithic at Kebara also suggests the presence of modern humans in the area by 43,000 years ago.

5

Tracing the northwards expansion of people into Turkey has been problematic. The Palaeolithic of Turkey has long been in the shadows, mostly because comparatively little archaeological research has been

carried out there.

6

Many Palaeolithic sites in Turkey are just ‘findspots’, where stone tools have been spotted on the surface. Relatively few

have been excavated, but in the last twenty years archaeologist have been striving to plug this gap, and some interesting

finds have emerged, which help us to trace the journey of those early European colonisers.

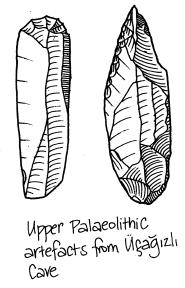

The archaeological site of Üçagizli lies on the rocky south-west coast of Turkey, about 150km north of Ksar ‘Akil, and near

the city of Antakh (ancient Antioch). The partially collapsed cave was first discovered in the 1980s, and excavations began there in earnest in the 1990s, leading to the discovery of Upper Palaeolithic artefacts in red

clay sediments. The tool manufacture at Üçagizli seems to follow a very similar pattern to Ksar ‘Akil: the oldest Upper Palaeolithic

layers in fact contain a mixture of ‘Middle Palaeolithic’ technology alongside more classic, retouched tools. Just as at Ksar ‘Akil, the Levallois cores disappear in the higher layers, to be replaced by prismatic cores, where blades

have been knocked off by soft-hammer or indirect percussion. But at Üçagizli there are also tools made of bone and antler.

The earliest Upper Palaeolithic layers date to between 41,000 and 44,000 years.

3

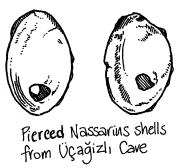

Throughout the Upper Palaeolithic layers at both Ksar ‘Akil and Üçagizli, the archaeologists discovered classic signs of the

Upper Palaeolithic – and of modern humans: ornaments. The vast majority are small seashells, pierced through to be used as

beads or pendants. More than five hundred shell beads have been found at Üçagizli alone. It’s possible to see how the holes

have been created in the shells – some by scratching away, while others seem to have been punched through with a pointed tool

– and it’s quite clear that these holes were made by humans and not by other, natural processes. There were shells from marine

snails

Nassarius

gibbosula

,

Columbella rustica

and

Theodoxus jordani

, as well as the pretty, ridged bivalve

Glycymeris

. From the large collection of shells at Üçagizli, it looks as if those hunter-gatherers also enjoyed the taste of seafood: bigger shells, from limpets (

Patella

) and the edible snail

Monodonta

also appear, unpierced, in the archaeological strata. The archaeologists were sure that these shells had been collected for

food as they were not wave-worn like the empty seashells that wash up on beaches, and, in addition, many of them were burnt.

The shell beads from Üçagizli are not – by a long stretch – the earliest ornaments: the pierced shells from Skhul in Israel

date to between 100,000 and 135,000 years ago.

7

Shell beads were also found in Blombos Cave, dating to around 75,000 years ago, and the evidence for ochre use goes back to

beyond 160,000 years ago at Pinnacle Point. These finds suggest that art and ornamentation is probably almost as old as the

human species itself. But the Üçagizli beads are useful as a marker for modern human presence. They show that modern humans

were bringing with them a shared culture, and perhaps an awareness of identity and a system of communication that did not

seem to have been there among archaic human populations.

3

There is a scarcity of Upper Palaeolithic sites in Turkey. Kuhn

6

argues that the Anatolian Plateau, most of which lies more

than a kilometre above sea level, would have been a cold, unwelcoming place during the late Pleistocene, and that modern humans

(as well as other animals) would have gravitated towards the warmer coast. With a higher sea level today, any Pleistocene

coastal sites would now be submerged. Nevertheless, Üçagizli is an extremely important site, a stepping stone into Europe,

with Upper Palaeolithic artefacts going back more than 40,000 years, anticipating the spread of the classic Upper Palaeolithic

culture, the ‘Aurignacian’, from east to west across Europe, between about 40,000 and 35,000 years ago.

8

This all seems to fit together very neatly, but we need to be aware that these initial movements into Europe are occurring

at an awkward time for radiocarbon dating, and some dates obtained during the twentieth century might need reassessment. And

not only do archaeologists and anthropologists argue about the exits from Africa, there is also debate about the route

into

Europe, and where Upper Palaeolithic culture began. Kuhn

6

seems convinced by the dating of Üçagizli, but also suggests that

this culture may represent a spread southwards from Europe, rather than northwards from the Zagros Mountains and the Levant.

Other researchers have argued that Upper Palaeolithic culture may have arisen in the Russian Altai, north of the Zagros Mountains,

with a dispersal of modern humans, carrying this technology, coming into Europe from around the Caucasus Mountains and the

northern coast of the Black Sea.

9

However, most researchers seem to agree that Üçagizli and Ksar ‘Akil fit very well with a model where modern humans, bearing

an Upper Palaeolithic, pre-Aurignacian toolkit, arrive in the Levant, spread north into Turkey, and then westwards through

Europe.

8