The Incredible Human Journey (34 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

‘We knew that the old type of M168 mutated to the new type about 80,000 years ago, in Africa. So if the Out of Africa hypothesis

was true, we would expect that everybody in China would be carrying the new type of M186. But if there had been an independent

origin of modern humans in China, we should be able to see that at least some people were carrying the old type.’

‘And what did you find?’

‘We did not see any old type in the Chinese population. In fact, we had a very large sample covering almost every corner of

East Asia, and

everybody

was carrying the new type of M168.’

The ubiquity of the M168 mutation in Chinese DNA showed that modern humans emerging from Africa had completely replaced earlier

East Asian populations.

1

Peking Man had no descendants alive today.

‘And what did that result mean to you?’ I asked.

‘Well, as a Chinese, of course I wanted to find evidence that we have ancient roots in China. That was my education,’ said

Jin. ‘It is what we are all taught. But, as a scientist, I have to accept the evidence. And the evidence showed that the recent

Out of Africa hypothesis is right. Regional continuity can’t be true.’

‘Do you think, on balance, that other genetic evidence supports Out of Africa?’ I asked him.

He was categorical in his reply: ‘I would make a stronger statement: it exclusively supports the Out of Africa hypothesis.’

Genetics also offered some insight into

how

the East had become colonised by modern humans. A greater diversity of Y chromosomes in the south, including among Thais and

Cambodians, tells the tale of initial colonisation of South-East Asia, followed by a northwards migration. And the Y chromosome tree suggests a very broad range for the initial date of entry into East Asia, at some time between 25,000

and 60,000 years ago.

2

Mitochondrial DNA analyses also show greater diversity in the south, and support the main theme of a south-to-north colonisation

of the Far East. The four main haplogroups in East Asia (B, M7, F and R) are all about 50,000 years old.

3

It is quite extraordinary that, despite the thousands of years since the initial colonisation of the East, and all the population

movements that have occurred since then, it is still possible to look into the genes of living East Asians and find the clues

to where they first came from. Like a piece of parchment that has been written over and over, the faint traces of the original

story are still there. Analysis of complete mtDNA sequences shows a distinction between northern and southern East Asians,

but more than that – a geographic structure can be discerned in the boughs, branches and twigs of the East Asian mtDNA tree.

4

But as well as the mitochondrial genetic evidence for a general migration from south to north, there are lineages in northern

East Asia – particularly C and Z – that are missing in the south. So where have these come from? Stephen Oppenheimer

5

traces

these lineages back to India, to early Asians who had skirted the western end of the Himalayas to reach the Russian Altai

and populate Siberia between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago, leaving archaeological traces at places like Kara-Bom. The Y chromosome

evidence mirrors the mtDNA phylogeography, with the North Asian founder population splitting east and west. Some headed west

to Europe, while the eastward-bound colonisers continued following the mammoth steppe all the way into what is now northern

China. Some remarkable details emerge from the complicated, over-written palimpsest: among the Ainu of Japan, a mitochondrial haplogroup

called Y1 seems to record a specific migration from north-east Siberia into the northern Japanese islands.

6

And the north-east Asian populations share lineages, like C, with Native Americans – but that is the subject of another chapter

entirely.

So it seemed that the East Asians were indeed descendants of the South-East Asian beachcombers, except for a few lineages

that had made their way east from Central and northern Asia. Also on the Y chromosome, the M130 marker seems to record a migration

along the South-East Asian coast, turning north to Japan, and there are a scattering of archaeological sites in Korea and

Japan dating to around 37,000 to 40,000 years ago that may record this wave of colonisation.

7

I wondered if Jin Li had any thoughts on the origin of East Asian features, and whether genetics could yet shed any light

on the development of these specific facial characteristics. Although he thought they may have first arisen in South-East

Asians, perhaps around the LGM, he was also sceptical about any association with cold adaptation. Another hypothesis puts

the origin and spread of East Asian features down to expansion of Neolithic populations with the advent of rice farming, but

that didn’t seem to fit with the suggested timing of the mutations either.

Li Jin wanted to pin down the relationship between genes and facial morphology – something that might help him answer where

and how East Asian features arose and spread.

‘We don’t know what features are determined by which genes. We are just starting to try to identify the genes underlying morphological

variation, and then we should be able to tell when exactly these features developed as well.’

He was about to embark on what sounded like an extraordinarily ambitious project: to relate genetics to morphology by collecting

anthropomorphic data from living people – effectively measuring them up – and using whole genome sequencing to look for genes

or patterns of genes that seemed to be associated with particular features.

‘We’re looking at a thousand people, recording their morphological features – and we’re in the process of doing whole genome

scanning.’

This was just the sort of research that would start to fill in that vast gap in our understanding, building a bridge between

genetics and morphology. And there were already some results …

‘We already know which genes underlie the orientation of hair

whorls,’ said Jin grandly, but with a wry smile.

It was clear that Jin Li was hugely excited by the potential of genetics to delve into the deep past and tackle the questions

of origins of modern humans and modern Chinese. I was incredibly impressed by his open-mindedness and objectivity: surely

the mark of a true scientist. And it was clear that the scientists at Fudan University were operating in a culture of academic

freedom. In a country where regional continuity was still a ‘fact’ taught to schoolchildren and endorsed by the state, Li

had been able to publish evidence for a recent African origin of East Asians.

We walked out of the Institute of Genetics and across a garden dominated by a large statue of Chairman Mao. It seemed ironic.

The poorly proportioned figure had been erected by students and Red Guards in 1966, but he was presiding over a very different cultural revolution now. Academic and individual freedom seemed to be winning back some ground.

Pottery and Rice: Guilin and Long Ji, China

Throughout prehistory, human populations have contracted and expanded, pushing into new territories and then withdrawing,

largely under the influence of climate change. But three major episodes of Stone Age ‘migrations’ or population movements

of modern humans can be discerned amid the general oscillations and milling about: the initial spread across and out of Africa,

resettlement of great areas of the northern hemisphere after the end of the Ice Age, and the spread of expanding populations

after the invention of farming.

1

The ‘Neolithic revolution’ and the origin of agriculture in the East was independent of that in Europe. Just as in the West,

the East Asian farmers were more successful than hunter-gatherers at a population level (if not really at the level of the

health and longevity of individuals). Higher levels of food production supported growing populations, and agriculturalists spread out of their homeland, carrying

their languages and lifestyles with them. Indeed, some archaeologists have argued that the facial – and dental – characteristics

of East Asians are so recent that they reflect that dispersal of a quickly expanding population of rice farmers as the Neolithic

got under way in the East.

2

,

3

It seems that the ‘Neolithic package’ of settlement, farming and pottery didn’t just suddenly spring into existence: the elements

we recognise as being characteristic of the Neolithic way of life emerged in a mosaic fashion. In the East, one of the first

elements to appear was pottery, pre-dating the development of farming. From the 1960s onwards, it was thought that the earliest

pots in the world belonged to the Jomon culture of Japan, dating to nearly 13,000 years ago. But new archaeological evidence

suggests that pottery may also have appeared at this time, and independently, in the Russian Far East and in south China.

4

In the late Pleistocene and early Holocene of south China, between 14,000 and 9,000 years ago, a culture appears which is

characterised by grinding stones, shell and bone tools – and the earliest pottery. Some archaeologists have called it ‘Mesolithic’,

comparing it with the same period in Europe; others prefer ‘pre-Neolithic’. I visited Guilin, in Guangxi Province, to see

the oldest known pot in China.

The landscape around Guilin was quite striking and beautiful. Out of the fertile plains rose huge, wooded, karst outcrops.

Some were cone-shaped, others more rounded. Guilin City itself was spread out on the flat ground among the karst hills, and

along the Li Jiang (Willow River). I was visiting soon after Qingming (pronounced ‘chingming’), the annual Chinese Festival

of the Dead, when tombs are swept clean, inscriptions touched up and new pine trees planted in cemeteries. Qingming literally

means ‘clear and bright’. I drove past graveyards with cairn-like tombs adorned with bright strips of red paper – prayers

for protection – and in one village a funeral procession was making its way down the road, with a banging of cymbals and drums.

The coffin was brightly decorated, topped off with a giant purple moth.

But I was visiting a much older graveyard: the cave site of Zengpiyan in Guilin, where I met the deputy director of the museum,

Mr Wei Jun. He opened the iron gate protecting the cave and we stepped inside.

Archaeologists had dug down through river sediments and the trenches were still open. Eighteen burials had been discovered

in the cave, mostly in flexed positions, and some covered in red ochre. As well as the human burials, Wei and his colleagues

had found pebble tools and animal bones.

‘But the most important discovery was the pottery we found here in 2001,’ said Wei.

‘It happened on the morning of 7 July. I recall it was raining very hard outside. There were about seven or eight archaeologists

working inside the cave. Then, suddenly, one of my colleagues came upon a piece of pottery that was a different colour –

much paler – than other pottery we’d found.

‘Professor Fu came over and looked at it carefully, and thought it might be very old.’

From the depth at which it was found the archaeologists immediately suspected the pot of being ancient; when it was dated,

from fragments of charcoal in the same layer, it turned out to be 12,000 years old.

‘From the radiocarbon dating, we know that these pieces of pottery are the oldest in China.’

These pieces of pottery were also among the oldest in the world. There was no evidence of plant or animal domestication at Guilin: the pots appeared to have been made by hunter-gatherers.

5

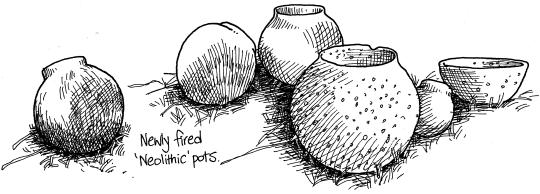

The following day, I met Professor Fu Xianguo, who had directed the excavations at the cave. The earliest Zengpiyan pots were

made with local clay, apparently deliberately tempered with quartz particles, and fired low, at less than 250 degrees C. They

were thick, wide-mouthed and almost hemispherical in shape. On a sunny day, in a field near Guilin, 12,000 years after pottery

was first made there, we recreated a pre-Neolithic pot. Fu’s chief pottery technician, Mr Wang Hao Tian, collected reddish clay, and we mixed it with smashed-up quartz particles.

Wang dug a round pit and we pushed pieces of clay into it, to form the hemispherical shape. Then we fired the pot, along with other pots that Wang had been busy making that week, on an open fire. Two brothers, Mr Liu

Cheng Jie and Mr Liu Cheng Yi, traditional potters from nearby Jing Xi (pronounced ‘Jing see’) on the Vietnamese border, came

to help with the firing. The Liu brothers laid logs across large stones to form a rack on which to place the pots, then pushed

burning sheaves of straw under the rack, moving the flaming bundle around with a long stick to sear the pots. After about

an hour of this gentle firing, the Lius built up a bonfire over the rack, with piles of straw and branches, and our pots were

hidden inside the blaze. Another hour later and the potters started to dismantle the still-smoking fire, hooking the pots

out on long sticks and setting them down on the ground, where they made a quiet tinkling noise as they cooled. Most of the pots had survived the firing – including our experimental pre-Neolithic cauldron, now dark grey but still speckled

with quartz.

Fu had his own particular theory about why the foragers around Guilin had started to make pottery.