The Incredible Human Journey (33 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

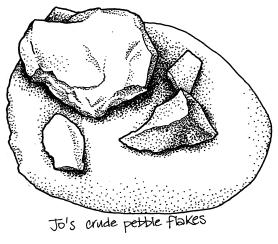

So perhaps those most basic of pebble tools are just enough to make more sophisticated tools out of plant material, and, perhaps,

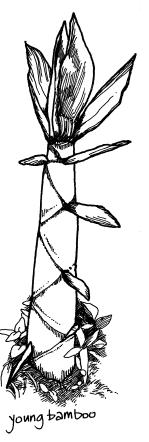

out of that most prolific subfamily of grasses in East Asia: bamboo. Bamboo is used so widely in the East today that it is

easy to imagine it would have been seized upon by the first colonisers. But there would be no trace of it left in the ground, only that of the stone tools which had been used to shape it. Although

Movius had concentrated on pebbles from which flakes had been struck, leaving a sharp edge on a heavy tool, perhaps he had

missed the point. Certainly, the flaked pebble could be used as a crude ‘chopper’, but the ‘waste flakes’ also had useful

cutting edges.

‘Why would you go to all that trouble of making a sophisticated stone tool,’ asked Jo, rhetorically, ‘when you can just take

a piece of bamboo, use that as a knife – and throw it away when you’ve finished? Because it’s everywhere.’

He was right. Zhujiatun was surrounded by bamboo forest. From a distance, the hillsides looked feathery: the wind blew through

the bamboo leaves as through a field of corn. Jo and I were going to try a bit of experimental archaeology. We used a large,

very crudely sharpened cobble to bash at the base of a bamboo trunk. The bamboo was thick, about 15cm in diameter, and I

prepared for some hard physical work to fell it. But after just a few minutes of bashing, the bamboo fell. With a little twisting,

it ripped away from its base, and we had the raw material we needed to try making some ‘Palaeolithic’ bamboo tools.

We took our length of bamboo down to the village, where this material was still being used to make all manner of things. There

were piles of long, thick bamboo trunks lying around, ready for construction. We were invited into a house in which there were piles of bamboo baskets stacked up, and an old man was in the process of

weaving one out of long, bendy strips of bamboo epithelium, or ‘bark’. In the yard, small ducklings had nestled together under

a bamboo cage.

Jo and I set to work on our bamboo tools. Using very basic, unretouched stone flakes, we pared down slivers of bamboo and

quickly made sharp-edged ‘knives’. I was surprised at how quick and easy the process was, though sceptical about just how

sharp and strong my bamboo knife would prove to be. The family had a chicken carcass ready for supper, and, using my brand

new bamboo knife, I made short work of butchering it, separating drumsticks, wings and breasts from the carcass (I may be

a vegetarian but I’m also an anatomist). The use of bamboo knives has been documented right across the Pacific. Ethnographic

studies have also shown that bamboo may even be used in preference to stone tools: the stone-adze-makers of Irian Jaya in

New Guinea, for example, like to use a simple piece of split bamboo for butchering.

5

And although my green bamboo knife had done the job well, Jo said it would have been even sharper had it been dried bamboo.

It was clear that bamboo could be used to make excellent cutting tools as well as being suitable for houses, baskets – and

even, as I had already seen, rafts. It was a wonderfully versatile material. (You could eat it, too. Bamboo became one of my favourite dishes on my visit to China, not as the more familiar, delicate

white bamboo shoots, but as inch-long pieces of thick shoots, rather like asparagus but crunchier – and delicious.) However,

the fact that bamboo

could

be used to make efficient tools isn’t proof that it was used. Neither is the fact that bamboo is still being used in some

places to make tools.

So was there any archaeological evidence of bamboo tools?

‘Well, no, not of the bamboo itself,’ admitted Jo. ‘But there is evidence of bamboo being

worked

– as well as other materials like rattan and palm wood – because there’s a high silica content in these materials. Using a

stone tool on bamboo leaves a very distinctive polish on that tool.’

This polish could be seen with the naked eye; Jo had brought along with him some stone flakes that he had used to cut bamboo,

and I could see the polishing quite clearly, next to the cutting edge.

‘How long does it take for this type of polish to develop?’ I asked him.

‘It starts to form immediately,’ he replied. ‘You can see the polish appearing within the first few minutes of cutting bamboo

or rattan.’

Employing microscopic use-wear analysis, it was actually possible to find out

exactly

what had been cut: different materials leave different tell-tale marks on stone tools.

6

Under a light or electron microscope, minute abrasions and polishing on tool edges provide clues that allow the material that

was cut to be identified. This means that archaeologists should be able to tell if stone tools have been used to cut into

bamboo, or rattan, or other materials. It may also be possible to find evidence of bamboo tool use as well. A study of experimentally

produced cut marks on bone showed that it was possible to tell the difference between cuts made with bamboo knives or stone

flakes, using scanning electron microscopy, which produces a very detailed, 3D image.

3

Jo had found examples of polish from cutting rattan on archaeological stone tools from a rockshelter in Timor. But those tools

had been only a few thousand years old.

‘What I’d really like to do is look at the very early, Chinese stone tools,’ said Jo.

As more Asian Palaeolithic sites are discovered, it is clear that the toolkits are more variable than was apparent to Movius

in the 1940s, when he drew a simple distinction between Acheulean hand axes in the West and chopper-chopping tools in the

East. His scheme also lifted the tools out of their environmental context: it didn’t take into account what the tools may

have been used for, or the raw materials that were available to the toolmakers. Archaeologists now caution against ranking

various toolkits in terms of how sophisticated the tools may appear, and also argue that Palaeolithic toolkits are generally

more diverse than previously thought, reflecting intelligent adaptations to a variety of environments.

5

However, even with new discoveries and the emerging impression of a wider variety of stone tools in East Asia, there is still

a clear distinction between the tools of East and West. Bamboo technology provides a tempting explanation for that difference.

Bamboo was everywhere, whereas it may have been difficult to find sources of good quality, workable stone in the rainforest.

Modern rainforest-based hunter-gatherers are mostly vegetarian and occasionally eat small animals – which would have been easily

butchered with bamboo knives, just as I had managed to prepare the chicken in the village.

Heavy-duty butchery tools would have been redundant in the rainforest.

3

I had seen how quick and easy it was to make a good, sharp bamboo knife, using just a simple stone flake. Bamboo technology

seemed as if it would have been a sensible, expedient adaptation to rainforest environments.

Although bamboo itself may be missing from the archaeological record, microscopic use-wear analysis of stone tools and examination

of cut marks on bones now provides archaeologists with an opportunity to test this theory. It may not be long before we know

for sure whether bamboo use really can explain the simplicity of stone tools in East Asia.

However, we are still left with a problem: there is no clear difference between the archaeology associated with archaic humans

and early modern humans in East Asia. Surely we should find some kind of ‘signal of modernity’ as soon as modern humans arrive

on the scene? Shouldn’t modern humans carry with them some badge of superior intelligence, a mark of technological sophistication

that has been lacking from previous human incarnations?

But are we once again falling into the trap of divorcing stone tools from their environmental context? We should not even

start to think about a tool assemblage without first firmly placing our toolmakers in their environment. The suggested bamboo

explanation for the basic stone tools of East Asia could work for archaic human populations just as it does for modern ones:

an intelligent solution to tool-making in a rainforest environment, where bamboo abounds.

So why

do

the tools change at around 30,000 years? If it’s not a different toolmaker, what is it? What is changing at that time? The

answer is: climate. And at 30,000 years ago, East Asia was starting to feel the cold and dryness of the approaching LGM. And

now we really do see the signature of modern human behaviour: when the environment changed around them, the modern humans

in East Asia adapted, by inventing new technologies.

East Asian Genes to the Rescue: Shanghai, China

I wanted to find out just what Chinese genes revealed about regional continuity versus a recent African origin. And I wanted

to speak to a Chinese geneticist.

It was time to leave Beijing and move on to China’s commercial capital, Shanghai. Beijing had seemed grey and somehow very

stolid. It felt like a place where dogma would have very deep foundations. On first impressions alone, Shanghai felt more

progressive, cosmopolitan and open. The centre of the city was an architectural palimpsest, with pre-war art deco hotels standing

next to concrete high-rises, with ugly flyovers and an elegant museum shaped like an ancient bronze cauldron. On the main

streets, international brands jostled for room alongside homegrown shops, and gigantic screens mounted high on buildings displayed

streams of advertisements. There was even a huge screen being carried up and down the Huangpu River on a boat. From the Bund,

I watched the Pudong district lighting up at dusk, as though it was, itself, a huge advertisement for commercialism and capitalism.

China was changing.

I drove out to Fudan University, to the Institute of Genetics, to meet Professor Jin Li. He showed me around labs where teams

of enthusiastic post-doctoral researchers were busy with pipettes and centrifuges. It was out of these labs, some seven years

earlier, that compelling genetic evidence about the origin of the Chinese people had emerged.

Li’s research group had undertaken a massive project designed to test the competing hypotheses about the origins of East Asians.

‘I wanted to see if I could find evidence for regional continuity in the genes of Chinese,’ he explained. ‘I decided to look

at the Y chromosome, and I started off using a marker of recent African origin, which would allow me to filter out those individuals

and leave me with other lineages that may have survived locally through regional continuity. We took thousands of DNA samples

from people all over China.’

So Li had started off wanting to prove the patriotic theory that the modern Chinese had a heritage in China which stretched

back, unbroken, to

Homo erectus

, a million years ago. The genetic marker he had used was a mutation at a site on the Y chromosome called M168, a swap of

a cytosine base to thymine, which previous studies had suggested was present in all non-African populations. But previous

studies had taken only limited samples from Asia. Li’s group had collected DNA samples from more than 12,000 men from South-East

Asia, Oceania, East Asia, Siberia and Central Asia, with the idea that, somewhere among them, there would be much more ancient,

non-African Y chromosomes.

1