The Incredible Human Journey (36 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

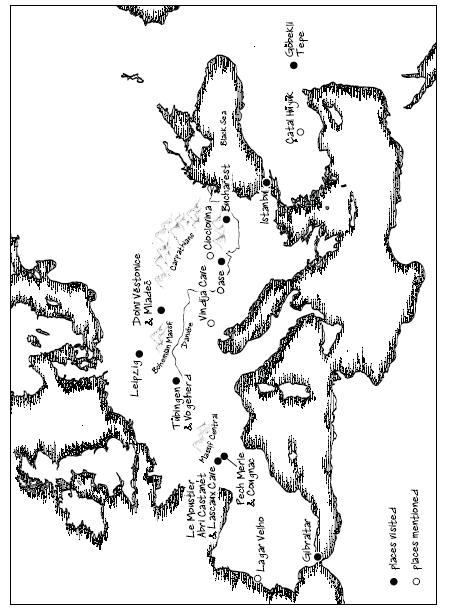

Crossing the Water into Europe: the Bosphorus, Turkey

Making my own way up through the Asian part of Turkey, I reached a watery barrier: the Bosphorus. This narrow strait connects

the Black Sea in the north to the Sea of Marmara, and at its southern end the Sea of Marmara narrows down again to form the

Dardanelles, connecting through to the Aegean Sea.

In Istanbul, I took the ferry to cross the glittering Bosphorus, from the Asian to the European side. I thought about the

early colonisers reaching this waterway, and Bulbeck’s ideas about coastal and estuarine adaptations, and the possible use

of watercraft in the Palaeolithic. It didn’t seem to me that the modern Bosphorus and the Dardanelles would have constituted

much of a barrier to the early pioneers.

In fact, when I looked into it, it turned out that the Bosphorus was dry during the Pleistocene. It wasn’t until after the

Ice Age that the sea level rose sufficiently to flood the Bosphorus and connect them. Boreholes drilled down through the sediments at the bottom of the strait show how and when the connection between the two

bodies of water was established: the Sea of Marmara spread northwards and eventually opened into an estuary at the southern

end of the Black Sea, around 5300 years ago, and the Bosphorus was formed. Interestingly, it looks like there was another,

intermittently open, connection between the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea during the Pleistocene, to the east, from what

is now the Gulf of Izmit.

1

So even if the Bosphorus wasn’t there to cross, there may have been times when the colonisers

would

have got their feet wet crossing from Asia to Europe.

From the Bosphorus region colonisers could have headed northwards to the coast of the Black Sea, or continue beachcombing

westwards along the Mediterranean coast, and it appears that they did both. There are a scattering of sites with Upper Palaeolithic

stone tools, on or close to the Mediterranean coast, in Italy, France and northern Spain, and there are also sites dotted

along both the European and Asian shorelines of the Black Sea. An important early Upper Palaeolithic site is Bacho Kiro, in

Bulgaria, where a ‘pre-Aurignacian’ toolkit – with lots of blades – has been found, dating to 43,000 years ago. Moving northwards

up the west coast of the Black Sea, the colonisers would have reached the great delta of the Danube, in modern-day Romania.

They could have then used the waterway as a superhighway into the heart of Europe: there are many Upper Palaeolithic sites

along the Danube and its tributaries. The conventional radiocarbon dates for this westwards spread across Europe suggested

it took place between 45,000 and 35,000 years ago. New, calibrated radiocarbon dates for these sites suggest that this dispersal

into central and western Europe happened fairly rapidly, between 46,000 and 41,000 years ago. This speedy spread across Europe

may have been helped by another episode of global warming, the Hengelo interstadial.

2

,

3

,

4

,

5

Face to Face with the First Modern European:

Oase Cave, Romania

My next destination was a site along that Danube corridor. I travelled to Romania, to meet geologist and speleologist (cave

expert) Silviu Constantin, who was going to introduce me to the cave where the earliest known modern human fossil in Europe

had been discovered.

From Bucharest, we drove east, following the Danube fairly closely, like our predecessors 40,000 years before. We drove and

drove, and eventually reached a small village in the south-western Carpathians, the name of which I cannot disclose because

the exact locality of the cave was secret. A couple of stray dogs chased our car up the hill, excitedly barking, but when

we stopped and got out they ran away. We were staying in the 7 Brazi (fir trees) Pensiune, high up on the hill overlooking

the village.

The following morning, we met up with the team of cavers who were accompanying us – Mihai Bacin (leading the team), Virgil

Dragusin and Alexandra Hillebrand – and sorted out caving gear for the trip before heading off to the cave itself. We drove

through wooded valleys and past abandoned factories, and eventually turned off on to a dirt track. About a quarter of a mile

later, we reached a point where the road had collapsed. We all got out to take a look, and, after hauling some large stones into the hole, decided that it was passable, and cautiously

drove the cars over the roughly stopped-up breach. It held. We pulled up just around the corner from the collapsed track.

The cave itself was below us in the steep-sided valley, and we scrambled down the wooded slope, lugging our equipment down

to the stream bank at the bottom. Once we were down, I could see the tall, slit-like entrance of the cave, with the stream emerging from it.

This was

Peştera

cu Oase, the Cave of Bones. It was incredibly exciting to be standing there, in front of a place that I had

read so much about. A colleague from Bristol University, João Zilhao, had been part of the team that excavated there in 2003–5, so I had heard

a lot about the cave from him. Unfortunately, he was in Portugal investigating another cave, but that left me in Silviu’s

capable hands – he had also been one of the excavating team, and he had dated the finds from the cave.

On 16 February 2002, a group of intrepid cave divers were exploring the cave. The cavers had made their way into the depths,

past a duck-under and through a longer, underwater section, and up a steep ramp to an area littered with animal bones. ‘They

found a human mandible, right on top of the flowstone. It was probably dug out recently by an animal. It was just sitting

there, waiting for someone to discover it,’ said Silviu.

When the mandible was radiocarbon dated, it was found to be 35,000 years old, the oldest known remains of a modern human in

Europe.

‘You must have been pretty excited to get that date back,’ I said.

‘I remember everyone was excited,’ said Silviu. ‘The oldest human was here, in Romania. We were proud that it was in one of

our caves.’

The cave was an exciting proposition for scientists studying this period of prehistory. In 2003, an international team of

archaeologists visited the cave, and discovered masses of bones – mostly cave bear, but also some other human material: fragments

of a skull. These pieces were found further down the slope than the mandible, in part of the cave that was subsequently,

and evocatively, named Panta

Strãmoşilor

(the Ramp of the Ancestors). The skull and mandible were from two different individuals.

The place where the bones were found is hard to get to now – and involves that dive.

‘The archaeologists were trying to figure out how such a massive bone deposit could come into the cave,’ said Silviu. As a

geologist and a caver, he had joined the team to answer this question. He could also help with dating – using uranium series

dating on stalagmites. From his investigation, it seems that

Peştera

cu Oase once had another entrance, allowing the cave bears access. In fact, the two galleries that lead off from the Ramp of the Ancestors both seem to have

had openings in the past.

Today, these entrances have collapsed, and are practically blocked off, although some small animals – such as rodents – still

fall down into the cave through the sinkholes.

1

The majority of the bones in Oase belonged to cave bears. There were also bones of other cave-dwellers such as wolf and cave

lion, which had presumably made their dens in there at various times. However, also found in the cave were skeletal remains

of distinctly non-cave-dwellers such as ibex and red deer. These could have been brought into the cave by people, but there

were no signs of such habitation in the cave, nor any cut marks on the animal bones to suggest that they had been eaten by

humans. That left geological processes and carnivores to explain the accumulation of bones in the cave. In 2005, the archaeologists

returned to excavate the cave; they found many more bones, but also important clues as to how the skeletal remains had ended

up there. Underneath a covering of stalagmite, they found a 30cm-thick layer of cave bear and other animal bones, many bearing

the tooth marks of bears and wolves. This looked like a collection of bones of animals eaten by carnivores denning in the

cave, as well as the cave-dwellers themselves. Under that was a layer of bones mixed with sand, gravel and cobbles, and these

were sorted by size – larger bones at the top of the slope, smaller ones at the bottom, and many of the bones in this layer

had rounded-off edges. These bones had been swept into this part of the cave by flooding. So it seemed that the animal bones

in Oase had ended up there through a combination of cave-dwelling carnivores bringing their dinner home, and flooding.

‘So how do you think the human bones ended up in the cave?’ I asked Silviu.

‘Most probably they had been washed in.’

There were no gnaw marks on these bones, so perhaps a person, or even a buried skeleton, had fallen in through a sinkhole

and then the bones had been washed further down the cave by floods.

1

Nevertheless, it seems rather strange that there are only cranial remains – a skull and a mandible, and no other parts of

the skeleton – but there are still a lot of bones in Oase. Perhaps the rest of the skeleton will yet be found.

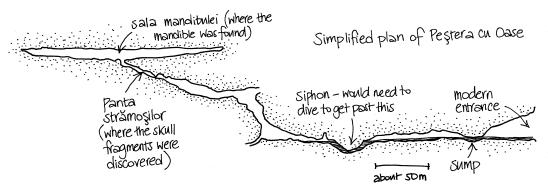

I followed Silviu into the cave – wading along the stream and into the first great gallery, with Mihai, Virgil and Alexandra

following behind. The roof was very high, and hung with enormous stalactites. Towards the back of this gallery were a series of pools with stalagmite

edges. We followed the stream around to the left, where the roof plunged down. We were lucky that day: there hadn’t been much rain the previous weeks and days, so the water level was low enough to enable

us

just

to keep our heads above water. In a wetter period this would have been a duck-under. Still, it was an awkward manoeuvre: under the water, the cave floor sloped away from the gap I was aiming for, and I couldn’t

get a foothold. As my feet slipped, I gave up trying to walk through the gap, and swam through it instead. On the other side,

I was wading shoulder-deep, hanging on to a rope to keep me close to the shallower right-hand wall. The floor of the tunnel

gradually rose up until the water was just knee-high.

We all made our way along this narrow, tunnel-like part of the cave. Sometimes the floor dipped down and we would plunge in

up to our chests again. Eventually, we reached a wider part of the tunnel, but the roof sloped down and down until it touched

the water: this was the siphon, and the end of the line for me. I would have had to dive to get to the Ramp of the Ancestors.

It was frustrating in a way, but I had known that I would only be able to get this far. I still felt privileged to have come

so close, and to have explored the cave where Europe’s earliest modern human had been found. Silviu and I sat down on a convenient

stalagmite and I asked him about excavating in the cave. It sounded arduous and difficult – getting to the site was one thing,

taking in tools and bringing back bags of sediment and bones, through the siphon and through the duck-under another altogether

– but the results had been worth it. When the skull had been dated, it was even older than the mandible: around 40,000 years old. And there were some things about the skull and mandible that seemed a little odd.