The Incredible Human Journey (51 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

‘So, 17,000 years ago, the ice sheets were pulling back from the west coast of Canada?’

‘That’s right, but the Queen Charlotte Islands had their own little ice cap, which was much thinner than the big one. This

is one of the reasons why this area deglaciated earlier. It’s not like a single wall of ice that’s pulling back.’

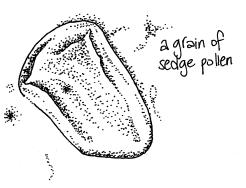

The pollen in the Dogfish Bank sample showed that this coastal plain was exposed between around 17,000 and 14,500 years ago

– after the glacial ice retreated and before the sea-level rise from all that melting ice flooded it. Careful analysis of

the pollen in the sediments from beneath the seabed showed that Dogfish Bank had been a wetland environment, with lots of

sedges, along with various grasses, horsetails, willow and the dwarf evergreen shrub, crowberry. Pollen from wetland species

like bayberry, as well as fossil green algae, indicated that the land was marshy.

2

‘Do you think people could have lived here?’ I asked.

‘Well, based on this – absolutely,’ said Rolf. ‘This was dry land, with vegetation growing on it.’

‘And do you think the coast could have formed a route for the first colonisation of the Americas?’ I asked.

‘There were a number of sites from the Gulf of Alaska right down the side of British Columbia that were free of ice, from

16,000 years ago. And, each summer, the green patches would have expanded. There were even forests starting to form on the Queen Charlotte Islands

when the inland corridor was still locked up in ice,’ explained Rolf.

The sample from the southern end of Haida Gwaii, from a site above sea level, showed that sedges also dominated the early

plant life there, but that there were lots of other herbs and shrubs as well. Some of these plants, like ferns, prefer warm,

moist habitats, whereas others, such as crowberry and bearberry, survive in cold, dry places. This mixture of plants is similar

to that found in the coastal tundra of modern south-western Alaska. The concentration of pollen grains in the sample gradually

increased over time, as the plants gained a firm foothold on the post-glacial landscape. By 15,600 years ago, the first trees,

lodgepole pines (

Pinus contorta

), had arrived and the environment of the islands changed from tundra to pine woodlands with ferns covering the ground between

them. Pine pollen can blow a long way, but the presence of this species on the islands was also confirmed by radiocarbon dating

of a lodgepole pine needle to just over 14,000 years ago. Other coastal sites in British Columbia have shown pine woodland

to be widespread by about 14,000 years ago. As the climate grew even warmer, the succession of plants continued: the pine

woodlands started to disappear, to be replaced by spruces.

2

‘People could have travelled down the coast, probably by boat, from oasis to little oasis. The environment was certainly suitable

for humans, but we’ll leave it to the archaeologists to find the hard evidence that they were actually there.’

After lunch in one of the pleasantly wooded courtyards of Simon Fraser University, I explored the campus. The original sixties

buildings were designed by architects Arthur Erickson and Geoff Massey, and the modernist design principles have been maintained

in later buildings, so that the whole scholarly city has a stylistic coherence and grace. I sat down to read in the calm serenity

of the Academic Quadrangle, where a huge jade boulder was reflected in the still waters of a pond. The monumental buildings

had a lightness and aesthetic appeal that I didn’t normally associate with sixties concrete architecture. Their futuristic

qualities had made them the ideal backdrop for sci-fi series: James Fraser University has featured in

The X-files

,

Stargate

, and as a city in the Cylon-occupied planet of Caprica in the film

Battlestar Galactica

.

Back in Ice Age Canada, though, and aliens aside, British Columbia held other clues to the potential coastal dispersal of

its earliest human inhabitants. Bizarre as it may seem, but very fitting for Canada, one of those clues is

bears

. The Haida Gwaii Islands are full of limestone and are rained on a lot: perfect conditions for cave formation. Limestone

caves are particularly good for fossil preservation, and so the Haida Gwaii caves seemed like a pretty good place to start

looking for fossils. In 2000, a team of Canadian palaeontologists and archaeologists started excavating the caves – and quickly

started to find animal bones. These included dog, mouse deer, duck – and bear. Radiocarbon dating showed the dog bones to be quite recent in palaeontological

terms: less than 2000 years old. But the bear bones were very exciting – they were much older.

3

I travelled north from Vancouver, taking the ‘Sea to Sky’ Highway along the magnificent coast of Howe Sound up to Squamish,

then winding through the wooded gorges of the Cheakamus River valley to Whistler. This ski resort – in summertime – was full

of holiday-makers going mountain-biking, whitewater-rafting, and shopping. But that day Whistler also hosted archaeologist

Quentin Mackie, who had kindly arranged to come down from the University of Victoria especially to meet me, and he had brought

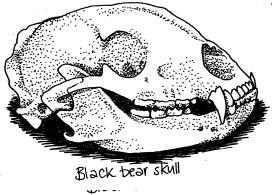

along a couple of old friends: two bear skulls from excavations on Haida Gwaii.

When I arrived in Whistler, Quentin Mackie was already there, in the foyer of the hotel, with the two bear skulls on a coffee table in front of him (I wondered what the other hotel guests thought of this). The skulls were different sizes – one was

a brown bear, the other a black bear – but both looked formidable beasts. They were ancient specimens, excavated from caves

on Haida Gwaii.

‘These are just a couple of the specimens we’ve discovered in the caves,’ explained Quentin. ‘We’ve found more than six thousand

bear bones, from black and brown bear, and some of them date to as early as 17,000 years ago.’

So, very soon after the peak of the last Ice Age, Haida Gwaii was supporting not only sedges and grasses, but large – very large – mammals.

‘We were really surprised to get this early date, because conventional wisdom suggested that, at that time, there would have

been nowhere for bears to live on the north-west coast: it would have been covered by ice. There was some pollen evidence

for ice-free areas, but we thought that these were small, very windswept, perhaps not very viable environments.’

‘How do you think the bears got there, that long ago?’ I asked.

‘With these early dates we have to consider one of two possibilities. Either these bears were able to get into the coast from somewhere [north] very early – as early as 17,000 years ago, or they

spent the last part of the glaciation on the coast, in some kind of refugium. Both of those are really interesting – because

if bears could get in early or if bears could survive through the LGM on the coast, then it implies that humans could have

done as well.’

I could see Quentin’s point – that the presence of a large mammal in Haida Gwaii might have implications for human migrations

3

– but I was also a little sceptical.

‘But you haven’t found any evidence of

humans

that long ago?’

‘Well, no. But the interesting thing about these bears is that they make a pretty good analogy for humans. They’re large land

mammals, they’re quite territorial, and they’re omnivorous. They eat berries, roots, insects, even small mammals like ground

squirrel – and they may even chase down deer and caribou. They’re also very good beachcombers. They will go along the strand

line – and I’ve seen them do this many times – roll over rocks and lick up sand hoppers and crabs. But they’re also quite

capable of taking migrating salmon from rivers.

‘Humans would have been able to eat pretty much anything that a bear would eat … so I think that if it was a good environment

for bears – which it clearly was – then it was a great environment for humans.’

Quentin had found some evidence of human activity dating back to 13,000 years ago. It seemed that people had been hunting

the hibernating bears at that time, which sounded like a highly dangerous pursuit, but Quentin said there were historical

accounts of people waking hibernating bears with burning braziers, then waiting by the cave mouth to spear the angry animal

as it emerged.

‘Bear meat is quite edible. I’ve eaten it myself. If you cook it well it’s delicious, and very nutritious. The bears’ winter

pelts would also have been extremely valuable to these people, and we also have a really good record of them making tools

out of bear bones, so it’s a fabulous resource from nose to tail.’

However, these bear hunters weren’t early enough to have been among the first colonisers of the Americas. But Quentin was

not about to give up the search.

‘These caves are still some of the oldest sites in Canada. And we feel fairly confident that in the next few years we’ll be

able to push that date back a little bit.’

The mitochondrial genetic lineages of brown bears have also been investigated – including mtDNA from bears preserved in permafrost

– and they tell us something very interesting. It seems that brown bears, like humans, came through Beringia – and had persisted

there throughout the LGM.

4

Not only that, the mtDNA of brown bears suggests that, having survived in refugia on islands off the western coast of Canada,

these formidable animals went on to repopulate the mainland from about 13,000 years ago.

I missed out on seeing actual bears in Canada (although I did see a whole bear skeleton in a gem shop window), but I did get

to visit a remnant of the Great Cordilleran ice sheet: the Ipsoot glacier, high in the mountains above Pemberton, near Whistler.

A helicopter dropped me off on the glacier, along with mountaineer Jim Orava, and I spent a thoroughly enjoyable day learning

to ice-climb. Equipped with ice axes and crampons, we crawled over the glacier – climbing and traversing vertical walls of

ice, leaping over crevasses with ropes for security. I had rock-climbed before, but it was a very different sort of climbing

on ice. In just one day, I began to understand

why

people want to climb mountains, but it also made me absolutely sure that the unbroken coast-to-coast glacier of the merged

Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets would have been an absolute barrier to hunter-gatherers at the peak of the last Ice

Age.

From one extreme to another, I also went snorkelling in the chilly coastal waters of British Columbia. Warmly wrapped in 5mm

of neoprene wetsuit, I explored the shallow waters around the edges and islands of Sechelt Inlet, north of Vancouver. As

well as plenty of sea stars and fish, I saw lots and lots of kelp. And, believe it or not (and at this point it does start

to feel as though archaeologists are clutching at straws, or seaweed, or whatever, along the Canadian Pacific coast), kelp

has also been implicated in the proposed coastal route into the Americas.

Kelp forests are incredibly rich ecosystems – among the most productive and diverse habitats on earth. They support a great

wealth of marine life: fish and shellfish, marine mammals and birds. For hunter-gatherers on a kelp-forested coast, the marine

resources are easily as rich as – if not richer than – those on land, provoking some archaeologists to call the potential

coastal route into the Americas the ‘Kelp Highway’. Bears come into the story again here: grizzly bears on the richly provided coast grow two or three times as large as their

inland cousins.

5

Kelp thrives in cool nearshore waters, preferring temperatures of less than 20 degrees C, and can even survive a winter beneath

sea ice. Today, the coastal kelp forests of the north Pacific stretch all the way from Japan to Baja in California. There’s

a break along the tropical coasts, where the sea is too warm for kelp, then it starts again along the Andean coast. The kelp

forests would have been there, in the rising post-glacial waters, so any prehistoric beachcombers would have been well provided

for. Today’s Pacific kelp forests are home to a huge variety of fish, shellfish (such as abalones, sea urchins and mussels),

seabirds and sea otters. Before Beringia disappeared beneath the waves, its bays and inlets supported large mammals like walrus

and sea cow. Although the sea level around western Canada early in the post-glacial would have been about 100m lower than

today, the coastline would have been almost as convoluted and fragmented as it is now. Any coastal hunter-gatherers

must

have had boats in order to get around and efficiently exploit this environment.

5

But as it has been argued that modern humans emerging from Africa – some 60,000 years before the Americas were even glimpsed

– were adapted to coastal and estuarine environments and probably had watercraft, it seems quite reasonable to assume the

early Americans would have used boats to navigate and forage along the coast.