The Incredible Human Journey (55 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

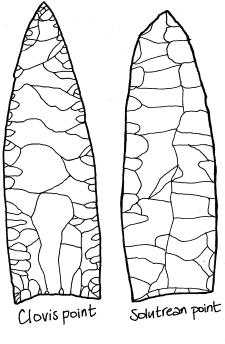

In fact, the closest stone toolkit to Clovis comes from a

long

way away, in western Europe. The similarity between Solutrean and Clovis points and blades is quite remarkable. Some archaeologists

have even suggested that this indicates a completely different origin and route for the peopling of the Americas: from France

and Spain, spreading around the North Atlantic.

8

It’s an interesting idea, but there is really no other evidence to back this up, and a lot of problems with the suggested

route: the Solutrean ended some 5000 years before Clovis started, there’s no evidence of any seafaring tradition in western Europe

and the way would have been blocked by ice sheets.

9

,

10

And then, of course, there are the genes of the Native Americans, which seem firmly to indicate an Asian origin of these

people. Having said that, some have argued that the X haplogroup found among Native Americans indicates a European connection

– as X is also found in Europe. Actually, this is probably right – but the connection is a very ancient one. The X lineages

found in Europe and America split some 30,000 years ago, when the ancestors of those particular groups of Native Americans

and Europeans were living on the Siberian steppe, before they went their separate ways to the west and east.

11

And recent genetic studies have picked up the X haplogroup among Mongolians, in the Altai region.

10

So it seems that the similarity between the Solutrean and Clovis industries may just be coincidental: an example of cultural

convergence in these two widely separated (in space and time) groups of Ice Age hunters.

(Months later, in a field in Exeter, back home in England, I was to meet Professor Bruce Bradley and his masters student,

Metin Eren. Bruce was quite clear that his hypothesis about the Solutrean-Clovis link and a North Atlantic route into the Americas had

not yet been refuted. Indeed, although the best-known Clovis sites were in the western US, he pointed out that the oldest and densest scatter of

sites was in the east. As he put it: ‘It’s thicker than the fleas on a dog in south-eastern US.’ He was also much more convinced by the cultural connection between

western Europe and North America, whereas, to him, the toolkit at Yana bore similarities to the Gravettian of Europe, but

had no real links with American toolkits. This conversation made me realise that the first route into the Americas was still up for grabs – and Bruce and his colleagues

were searching for evidence in the east. He was sure the Solutreans could have made their way, by sea, around the North Atlantic. After all, those people had bows and arrows, and spear-throwers. ‘The idea that they didn’t

have boats – give me a break!’ exclaimed Bruce.)

The development and dispersal of Clovis

is

quite remarkable – in just a few hundred years it had spread through America. But if this wasn’t the culture carried by the

first colonisers, how was it disseminated? Mike’s idea was that Clovis was a ‘technocomplex’ – a tool-making trend – taken up and shared by a wide range of ethnically

diverse people whose ancestors had

already

dispersed across North America.

4

Clovis spread rapidly during the last centuries of the warmish Allerod interstadial, and the overlap between dates from sites

widely spaced across North America makes it impossible to know where exactly it started and in which direction it advanced.

It disappears from the archaeological record almost as swiftly as it appeared, at the onset of the Younger Dryas stadial,

being replaced with another toolkit, named after Folsom, where it was first found.

2

,

12

The date of the disappearance of Clovis takes us back to that comet impact idea. The black layer and the beginning of the

Younger Dryas seem to mark the end of the megafauna in the fossil record of North America, but also the end of Clovis in the

archaeological record. So did that comet strike indeed finish off the mammoths and mastodons and sloths and create such environmental

destruction that human survivors were forced to reinvent their subsistence and devise new toolkits?

Later that afternoon I met archaeologist Andy Hemmings for a practical demonstration of the deadly efficiency of Clovis hunting

technology. He showed me how the fluted base of a Clovis point enabled it to be hafted into a notch on a shaft. He also showed

me bone points, another characteristic feature of Clovis toolkits. Three bone and ivory hooks have been found, of Clovis age,

that suggest these hunters used spear-throwers – atlatls – to launch darts.

1

We had a go at throwing darts (both bone-tipped and metal-tipped – Andy wasn’t keen on breaking the precious stone tips),

using an atlatl, at our target: a car door. It took me a while to get the hang of aiming the contraption, but, when I did,

I managed to make a decent hole in the door. I was suitably impressed. The atlatl allowed the dart to be launched with such

force that it penetrated sheet steel. And, in Andy’s capable hands, it was even more of a precise and vicious weapon. So the

Clovis people certainly had the technology to kill massive animals like bison and mammoths – just not all the time.

It was now time for me to travel south and investigate the story in South America. There are no Clovis sites in Central or

South America, although several of a similar age have yielded a basic flake technology which also includes some ‘fishtail’

points, some of which have fluted bases like Clovis points. But they are not Clovis: these sites represent different cultures,

and adaptations to a very different environment, in South America – contemporary with Clovis sites in the north. One such

site is Pedra Pintada, in the Brazilian Amazon, where excavations at the painted cave in the rainforest have yielded detailed

information about the lifestyles of the South American palaeoindians. Sites like this constitute a significant challenge to

any hangers-on of the ‘Clovis first’ theory, as it is hard to imagine how colonisers moving down through the ice corridor

could have reached South America that quickly.

Over the decades, several sites in South America with apparently pre-Clovis dates have risen to fame, and then been knocked

down, as the bastions of ‘Clovis first’ have picked holes in their archaeological procedures or dating methods. But there

is one site in particular that has stood up to scientific scrutiny: Monte Verde in Chile.

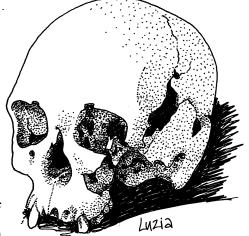

On my way to the Amazon, and Pedra Pintada, I stopped off in Rio, where one of the oldest skulls in the Americas is kept in

a box in the museum.

Upstairs, Rio Museum was like a palace that someone has forgotten to look after. The high ceilings were falling down, exposing

beams and lath, and the paint was peeling on the stuccoed pilasters. Most of the huge rooms were divided into offices and

corridors by the careful arrangement of filing cabinets and cupboards to form party walls.

In a large, dusty room somewhere in one corner of the museum, empty but for a huge wooden table, Walter Neves set down a metal

case. He sprung the locks and carefully opened the lid. Inside was an almost complete skull. He lifted it out and set it down on

a ring-doughnut-shaped piece of foam on the table. I was looking at the face – albeit the skeletal face – of an ancient American.

This was just one of the skulls found in the cave of Sumidouro (meaning swallet or sinkhole) in Lagoa Santa, in Brazil, in

the nineteenth century. The Danish naturalist Peter Lund had discovered the human remains in association with the fossilised

bones of megafauna, and had therefore proposed that people had been in the Americas at the same time that the giant beasts

were around. This was long before any Clovis sites were discovered in North America, and Lund’s contemporaries found it impossible

to accept his assertions about the antiquity of those bones. But archaeologists returning to the caves in the twentieth century found more human skeletons, in the same layers as megafauna.

In the 1970s, a skeleton was excavated from sediments that contained charcoal. Radiocarbon dating of this charcoal showed the skeleton to date back to the end of the Pleistocene, around 13,000 years ago.

Lund was at last vindicated.

1

The skeleton became known as ‘Luzia’ – and it was Luzia’s skull that Walter Neves had placed on the table before me.

‘I am proud to introduce you to Luzia,’ said Walter.

‘She is probably the oldest human skeleton ever found in the Americas. And what I realised back in 1989 was that the morphology

of these skulls of the first Americans was very, very different from the skulls of nowadays Native Americans.’

It

was

an odd looking skull. It didn’t really look Asian. Everything I’d found out so far about the origin of the first Americans

pointed to a homeland in East Asia – but this skull didn’t appear to have much in common with modern East Asians. I said so.

‘No, and it’s not just this skull,’ said Walter. ‘We have recently published a paper with eighty skulls from Lagoa Santa and

also like seventy skulls from Colombia and they all show the same trends.’

I knew the paper. It was the biggest sample of early American skulls that had ever been studied. After taking a suite of measurements

from the Lagoa Santa skulls, Walter had then compared this data with Howell’s database of measurements from more than 2500

skulls from around the world. He had used powerful multivariate statistics – that allow many different measurements to be

compared all at the same time – to look at how close the early Brazilian skulls were to crania from other populations. And

the results showed that the Lagoa Santa skulls were closer to Australians, Pacific Islanders and even Africans than they were

to north-east Asians or modern Native Americans.

2

Present-day Native Americans have a similar skull shape to modern north-eastern Asians: the braincase is short and wide, the

face is broad and wide, with very little protrusion of the jaw, the nasal opening is high and narrow and the eye sockets are

roundish. In contrast, Luzia’s skull was long and narrow, with a quite pronounced, projecting jaw, and broad, rectangular

eye sockets and a wide nasal opening – more like Australians, Melanesians and sub-Saharan Africans.

But how does this fit with the idea of early Americans coming from north-east Asia, through Beringia, into the Americas? Could

it even be taken to suggest a trans-Pacific crossing from Australo-Melanesia to South America? Walter was quick to dismiss

this idea.

‘We never suggested that. We never thought that,’ he said firmly. ‘If you go and see the few human skeletons of the final

Pleistocene in Asia they also look like this – not like today’s East Asians. So these populations showing Australo-Melanesian,

or even an African morphology, they were in East Asia by the final Pleistocene. So we have no doubt that Luzia’s people also

came from Asia using the Bering Strait as the entry to the Americas.’