The Incredible Human Journey (53 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

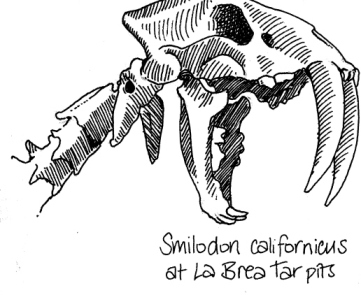

Hunting American Megafauna: La Brea Tar Pits, Los Angeles

Having had my appetite whetted by the remains of those diminutive mammoths on Santa Rosa, I wanted to find out more about

the large animals that roamed the Americas during the Ice Age.

Soon after I started working at Bristol University, I met colleagues in Earth Sciences who showed me some of the collections

held in that department. There was one room in particular that fascinated me: there were samples of rocks from around the

world, and, in a large glass cabinet, the impressive skeleton of a sabre-toothed cat. The bones were dark brown, almost as

though they had been carved out of ebony. The stuff that had turned the skeleton that colour was tar. The cat was a composite

skeleton, made from bones that had been dug up from the La Brea tar pits in Los Angeles. It had been brought to Bristol University

by the explorer and famous palaeontologist Bob Savage, who was a professor in the Department of Earth Sciences during the

fifties and sixties.

I was, therefore, very excited to be visiting the tar pits themselves. I had driven down the Californian coast from Santa

Barbara to Los Angeles (stopping off to watch surfers at Malibu Beach on the way), and now I was heading into the heart of

the city, to get a close look at the amazing palaeontological treasures that had emerged from the tar. I approached La Brea

Museum around the edge of a lake, filled mostly with water, but with tarry edges, and huge methane bubbles rising to burst

on the surface every few seconds. There I found myself face to face with life-size – full-size – mammoths. A great bull mammoth

had become mired in the tar pit, and, on the bank, a cow and her calf were looking on helplessly. They were good models:

it was almost as if I’d been transported back 20,000 years in time.

Inside the museum itself were reconstructed skeletons of a range of animals that had met sticky ends – in the most literal

sense – in the tar pits: giant sloths, horses, camels, mammoths and mastodons, sabre-toothed cats, lions and dire wolves,

an extinct species of wolf that used to live in both North and South America. In a glass-walled laboratory, palaeontologists

worked away, cleaning and preparing the specimens that were still emerging from the tar pits. I went through a door that

took me from the public side of the museum into laboratories and store rooms, where I met the curator, John Harris. I quickly

discovered that John had also been at Bristol University, studying for his Ph.D., and he remembered Bob Savage’s sabre-toothed

cat from La Brea.

John showed me some of the museum stores: they comprised what seemed like endless corridors lined with shelves and trays containing

thousands – millions – of bones from the tar pits. The bones were not fossilised in the true sense of the word: they had not

turned to stone but were still bone because the tar had preserved them. Then John took me outside, to a pit where excavation

was still going on. The pit was almost 10m deep and about 10m square. Down at the bottom of the pit, working away in the black,

sticky sludge, were three young palaeontologists – Andrea Thomer, Michelle Tabencki and Ryan Long – all of whom were themselves

well covered in tar. I sensibly donned a forensic-like white suit and started to descend the ladder into the pit, where I

could safely stand on boards to one side.

‘This is a strange job,’ I offered, gingerly making my way down the ladder into the tarry trench.

‘It’s basically the strangest job in the world … digging up the bones of dead animals out of tar,’ said Andrea.

‘And it doesn’t look like very nice stuff to excavate.’

‘No, it’s terribly sticky. Especially in the summertime. As it gets hotter it gets stickier.’

Around her Wellington-booted feet I could see bones sticking up out of the tar. The more I looked, the more I saw. It was

like a mass grave of Ice Age beasts.

‘We’ve had visiting palaeontologists come by who are just astounded to see this many fossils in one place. It’s probably one

of the richest fossil deposits in the world,’ Andrea told me.

‘And what type of species have you found?’ I asked her.

‘Well, the most common animal we find is the dire wolf. And the second most common is the sabre-cat. We have a very strange

predator– prey ratio – we have way more predators than we do animals that they eat. We think it’s because of the way that

the animals became trapped in these tar pits: a large herbivore would walk in, get stuck, and then all of the carnivores would

come and try to eat him, and then they would get stuck. About 70 per cent of the animals are predators rather than prey, and

that’s completely backwards.’

‘And how old are these fossils that you’re getting out of this pit?’

‘Well, down at the bottom, they’re 40,000 years old. And they’re not actually

fossilised

. They’re still bone – you get incredible detail.’

Michelle was trowelling the surface of the tar, removing a wet, oily layer so that excavation would be easier.

‘It’s called glopping,’ she said. ‘We have to do this every day before we really start work excavating bones from the pit.

The tar is constantly rising up. If we didn’t do this every single day, the pit would start filling up with liquid asphalt

again. We’re fighting nature, and it’s a losing battle.’

Climbing back up out of the pit, I asked John about the scale of the operation.

‘Since 1969 we’ve taken more than 70,000 bones out of this particular locality. All together we’ve got something like three

and a half million specimens in our collections – representing more than 650 species of animals and plants.’

I asked him if they excavated all year round.

‘No. We now only excavate during the summer. We do a ten-week excavation season and in just ten weeks we take out between

one and two thousand bones.’

It was clearly a huge job and the tar pits seemed almost bottomless. And it wasn’t just the planned excavations at La Brea itself that kept the palaeontologists busy. Construction work in downtown

LA often turned up tarry surprises, and a recent sewer trench had unearthed tonnes of tar-soaked sediment – full of bones.

I looked over to where John was pointing, just behind the tar pit where excavations were ongoing, and there were masses of

industrial containers, full to the brim of sediment, waiting to be excavated. John was going to have to pull his workers out

of the pit so that they could focus their attention on this unexpected haul of tarry bones.

Among all those Ice Age skeletons, only one human has ever been found.

‘It’s not that surprising,’ said John. ‘If you get stuck in a tar pit then you’re likely to meet your end there – unless you

have friends to pull you out.’

The tar pits gave a wonderful insight into the richness of animal life in ancient California. It was also obvious that the

vast majority of these large animals were no longer with us. Just as in Eurasia and Australia, the arrival of humans in the

Americas seemed to coincide with the demise of the megafauna.

‘The peculiar thing,’ John continued, ‘is that about 13,000 years ago these large creatures disappeared – and it’s one of

the big mysteries of American palaeontology.

‘Several people have come up with different ideas about how and why they disappeared. This was, after all, right at the end

of the Ice Age; there would have been climatic change and environmental change. But that had happened at least ten times during

the Pleistocene so that, in itself, climate change wouldn’t have caused the extinction of the megafauna.

‘Thirteen thousand years ago is about the time when humans arrived in North America, and some people think that it was humans

hunting the megafauna, or introducing diseases against which the megafauna had no immunity, that was part of the cause.’

La Brea tar pits don’t contain any evidence of human predation, but there are other sites in America that show, unequivocally,

that humans were hunting mammoths. But, just as on other continents, whether or not humans hunted the mammoths and other megafauna

to extinction, or whether changing climate and environment played a more significant role, it is difficult to know.

But John said that there was another, rather intriguing, theory about the disappearance of the American megafauna that had

recently exploded on to the scene.

‘The third suggestion that’s come up recently is that, apparently, there was an explosion of an asteroid right over the Great

Lakes region of North America at around 13,000 years ago …’

When I was in Arlington Springs and looking at the side of the gully (now eroded much further back than when Phil Orr discovered

Arlington Woman), John Johnson had pointed out several black layers in the section. Most of them were probably due to forest fires that occasionally ripped through the island’s vegetation. I had seen the results

of recent forest fires in the hills above Santa Barbara: blackened trees and a thick layer of ash over the ground.

But it seems that one of these black layers represents something more than random and sporadic forest fires. Across North

America, at more than fifty sites, a particular black layer has been found that dates to 12,900 years ago. The timing of this

layer coincides with the onset of the Younger Dryas cool period, and with the extinction of the North American megafauna: mammoths, mastodons, ground sloths, horses and camels. Proponents of the asteroid hypothesis suggest that human overkill and

climatic cooling are both inadequate explanations of megafaunal extinction. While mammoth and mastodon kill sites have been

identified, there are none for the other thirty-three genera of megafauna that also disappeared. And previous cold spells similar in degree to the Younger Dryas had not resulted in mass extinctions.

1

Geological analysis of the 12,900-year-old black layer from several sites revealed that it contained not only charcoal, carbon

spherules and glasslike carbon indicative of intense forest fires, but also rather more strange components, like nanodiamonds

and fullerenes containing extraterrestrial helium. These are very rare things indeed: they are found in meteorites and in

the ground at extraterrestrial impact sites. So the suggestion is that the continent-wide wildfires were caused by a comet

hit.

1

No crater has yet been identified, but the researchers suggest that perhaps there is none to find: maybe the comet crashed

into the Laurentide ice sheet, making very little mark on the earth beneath the ice – or perhaps it exploded in the air. In

1908, something from space – either a burnt-out comet or an asteroid, less than 150 metres in diameter, exploded in the atmosphere

above Tunguska in Siberia. The resulting airburst set fire to 200km

2

of forest, and knocked down trees over a wider 2000km

2

,

while leaving no crater. Perhaps the widespread fires of 12,900 years ago were caused by multiple airbursts or impacts.

Maybe this proposed impact even set off the Younger Dryas, with clouds of soot and smoke from the forest fires blocking out

sunlight. Perhaps the impact knocked off parts of the ice sheet, with rafting icebergs bringing down the surface temperature of the

Arctic and North Atlantic oceans. It’s an intriguing hypothesis, and the timing certainly works. An extraterrestrial impact

around 12,900 years ago, sparking off continent-wide forest fires, environmental destruction, and subsequent cooling

could

have wiped out the American megafauna.

But other archaeologists argue that there is no need to look to the stars for an explanation of the disappearance of the large

Pleistocene mammals of North America. For Gary Haynes of the University of Nevada the disappearance of thirty-three genera of large mammals

at the same time as the appearance of distinctive Clovis spear points in the archaeological record is not a coincidence.

2

He argues that humans have been known to hunt herd animals to extinction without any ‘help’ from climate change or extraterrestrial

impacts. Haynes also draws attention to the knock-on environmental consequences of losing large ‘keystone’ species, like mammoth

and mastodon. These animals modify their environments, opening up areas of grazing for smaller herbivores. In Africa, large herbivores help to keep grassland savannah productive. Archaeologists have argued that the loss of these large grazers in Beringia may even have caused a shift from productive grassy

steppe to moss-tundra. In other words, once humans had impacted particular species of megafauna, the loss of those animals

would have further ecological consequences, spreading out to affect other species as well.

2

Haynes argues that the climatic changes suggested by some to be instrumental in the demise of the megafauna did not happen

at the right time, as the Younger Dryas cold spell succeeded rather than preceded some extinctions (although this is not necessarily

at odds with the comet hypothesis, as the more immediate effects of the impact could have finished off the megafauna). And

there are the archaeological kill sites that demonstrate that the Clovis hunters despatched mammoths. Haynes makes the case

that mammoth and mastodon hunting would have been a sensible strategy for the Pleistocene hunters of North America.