The Incredible Human Journey (56 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

He thought his results were entirely compatible with a colonisation of the Americas from the north, but that the early Americans

were much more morphologically diverse than Native Americans are today, and included a lot of people – like Luzia – who didn’t

look at all East Asian.

Walter’s argument was that these Brazilian skulls suggested that a model of just one population expansion into the Americas

was too simple. He advocated that some people had come into the Americas before what we know as typical East Asian features

had developed, or at least while there was a more diverse range of morphologies in East Asia: with more people who still looked like the original beachcombers. I was reminded of the Upper Cave skulls from Zhoukoudian:

they also lacked classic ‘East Asian’ features.

3

Then, according to Walter, there was a later arrival of people with faces more like modern East Asians and Native Americans.

Other physical anthropologists looking at skull shape have also found evidence for a two-wave colonisation of the Americas.

Marta Lahr, of Cambridge University, found that skull shapes of modern Native Americans were similar to those of East Asians,

but that skulls from archaeological populations from Tierra del Fuego and Patagonia showed a more ‘generalised morphology’.

4

In 1996, a skeleton was discovered in Kennewick, Washington State. The skull was dated to about 9300 years old, and also appeared

to be closer in shape to the Ainu of Japan and to Pacific Ocean islanders than to Native Americans.

Walter was aware that this idea of two migrations into the Americas didn’t fit with the single migration revealed by genetics,

5

but he suggested that this discrepancy could be explained if some of the original genetic lineages have been lost, just as

people who looked like Luzia had disappeared over time.

1

,

2

Combining the fossil and genetic data, Stephen Oppenheimer has suggested that there might have been

three

genetically, morphologically and culturally distinct populations that moved from Beringia into the Americas. This harks back

to that idea of Beringia as a staging post, with various, different-looking populations originating in various parts of Asia

moving in, and then expanding into the Americas. Oppenheimer’s three populations include a group descended from the original

beachcombers of Asia (these would be robust people like Luzia); a group connected with later ‘East Asian’-looking people;

and another group from the Russian Altai (refugees moving east from Siberia during the peak of the Ice Age, and sharing the

mitochondrial X lineage with northern Europeans, descendants of westward-moving refugees).

6

But whether or not these two (or three) morphologically, and perhaps culturally, distinct populations came down into the Americas

at the same time, or in different waves, is currently very difficult to pin down. If these populations all flowed into America

at the same time, this does not seem to explain why none of those early Americans (or, at least, the ones discovered to date,

including Luzia and Kennewick Man) look ‘East Asian’.

But recently a large study of more than five hundred skulls from late Ice Age America all the way to the present, including

skulls from Lagoa Santa, suggested a synthesis between the genetic single-wave model and Walter’s ‘Two-Components’ model.

The researchers proposed an initial wave of colonisation, by a variable population from Siberia and Beringia, where East Asian

and robust, palaeoamerican types like Luzia formed opposite ends of a continuous spectrum of variation. After colonisation,

the northern, circumarctic groups then maintained continuous contact, allowing diffusion of that extreme north-east Asian

morphology with facial flatness and projection of the cheekbones to America. This could explain the similarity between Siberian

and Aleut-Eskimos.

7

Some anthropologists urge caution over reconstructing past migrations based on craniofacial shape: European Upper Palaeolithic

skulls appear closer to non-European skulls in Howell’s database than to modern European skulls, despite the genetic indications

that most modern Europeans are descended from Upper Palaeolithic populations. It seems that, all over the world, skull and face shapes have changed a lot since the first colonisers arrived in the various

continents.

8

What is clear, though, is that there is no longer anyone looking like Luzia in the Americas today. Stephen Oppenheimer has

suggested that the Olmec statues have this ‘African’ look, indicating that there may still have been people of this type living

3000 years ago. Walter Neves suspected that the ultimate disappearance of this robust type may have been fairly recent – perhaps

even since European contact with the New World. He showed me a reconstruction of Luzia that had been made by forensic artist

Richard Neaves. As Luzia had a projecting jaw, he had given her broad lips. In the flesh she certainly looked much more African

than East Asian.

It is clear that there are quite a few different opinions and different explanations for the variation seen in the early palaeoindians,

compared with Native Americans today. I imagine the picture will get clearer and some kind of consensus will emerge as more

fossils and artefacts are found, and more genes analysed. The complete story of the first Americans has yet to emerge.

Ancient Hunter-Gatherers in the Amazon Forest:

Pedra Pintada, Brazil

From Rio I flew north-east – to the Amazon. I was bound for an archaeological site that held information about how the early

Brazilians had lived.

We flew over the lower reaches of that largest of rivers, which broke into skeins of water that meandered and reunited, and

over vast stretches of forest, to land at a small airstrip at Santarém. I alighted from the plane into a warm breeze. Clouds

of lemon-yellow butterflies were streaming across the runway, flying with the wind.

From Santarém I caught a ferry to Monte Alegre (pronounced by the locals as ‘monchalegray’). The trip took around five hours,

and, like all the other passengers, I bought myself a hammock to hang up on the double-decked ferry. By the time we were ready

to leave the quayside in Santarém, the decks were festooned with a bright rainbow of hammocks: stripy, checked, fringed, and

embroidered. By mid-afternoon just about everyone was tucked up in their hammocks, gently swaying with the motion of the boat,

in the shade, out of the dazzling glare of the overhead sun.

Arriving at Monte Alegre close to sunset, I was met by Nelsi Sadeck as I got off the ferry, still swaying slightly. The next

morning, we set off from the small town on a road which quickly turned into a dusty, rutted track. We were heading for Pedra

Pintada, the ‘Painted Rock’. Nelsi was a local guide, and had dug at Pedra Pintada for archaeologist Anna Roosevelt, of the University of Illinois, who

had run excavations at the site during the early nineties.

Throughout South America, stone tools, including triangular points, have been found which are quite distinct from the North

American complexes. Most of them are undated, so it’s hard to know how they fit into the story of the colonisation of the

Americas. Some such points had been discovered in the lower Amazon region: very different from fluted Clovis points, these

were long and thin, with downturned ‘wings’ and a stem for attachment to a shaft. Other archaeologists had assumed them to

be Holocene, made some time in the last 10,000 years. But Anna Roosevelt wanted to pin down their age. In order to do this,

she needed to find a site where the archaeological layers were well preserved: it was no good just looking at surface finds. Cave sites seemed ideal – there was a good chance that early sediments would

have been preserved intact – and Anna knew that there were lots of caves and rockshelters in the sandstone outcrops around

Monte Alegre. Roosevelt’s team began their investigations by surveying these caves, mapping them and testing the deposits

inside using an auger to remove cores of sediment for inspection.

1

I was expecting to be venturing deep into the rainforest, but in fact the landscape around Monte Alegre was dominated by low-level

woodland and shrubby pastureland, where skinny white cows and horses grazed. Nelsi and I rattled along in the Toyota Land

Cruiser, stopping to machete back fallen trees on the track, and eventually coming to a halt at the base of a large outcrop.

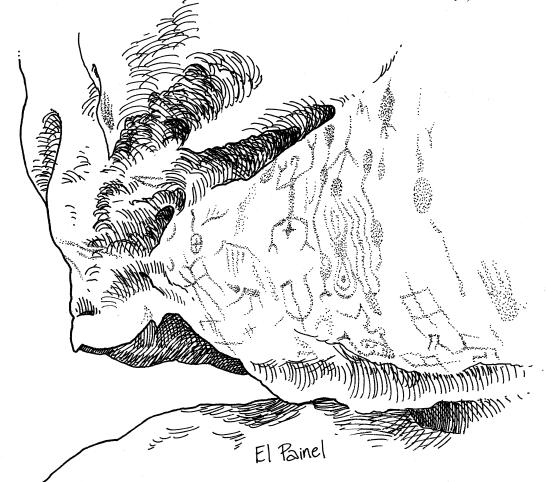

Nelsi led me up the slope to see a painted rockshelter, called ‘El Painel’. There were strange, abstract shapes, some looking

like animal forms, one like a woman giving birth. There were also geometric patterns, and handprints, all in red and yellow

ochre. Up on the rocky outcrop, looking down on the Amazon, I could still see those yellow butterflies on their journey, with

the wind. And, high above us, black vultures circled.

Then we went on to the Caverna da Pedra Pintada itself. We walked through a narrow cleft, which was open at the top, with

tree roots hanging down like lianas inside the cave. There were bats roosting high above us, on an overhang. I pointed them

out.

‘Yes … vampire bats,’ said Nelsi.

There were also peculiar, long-bodied wasps flying in and out of small nests, suspended by papery stalks from the walls of

the cave. I proceeded with caution. We scrambled down into the main cave, which opened into a wide mouth. We were looking

down on to the Amazon flood plain. On the walls were more paintings in red ochre.

The augured samples from Pedra Pintada suggested that the archaeology in the cave was undisturbed, and, in the early 1990s,

the archaeologists had started to excavate.

‘This is where we dug in ’91,’92 and ’93,’ explained Nelsi, gesturing to the floor of the cave entrance. ‘We excavated down

to two metres.’

There were plenty of remains in the more recent, shallower layers, and then the archaeologists found a ‘sterile’ layer of

sediment – containing no archaeological finds. But below that there was a deep layer full of animal bones, shells, burnt

plant remains, stone tools – and pieces of ochre: traces of the earliest inhabitants of the cave. Among the thousands of stone

flakes, there were twenty-four finished stone tools, including stemmed, triangular points made from quartz-like chalcedony,

that may have been used as spear or harpoon points. There were bones from amphibians, tortoises and turtles, snakes and mammals

– but most of the bones were from freshwater fish. The archaeologists found further evidence of the dietary breadth of the

ancient Amazonians from plant remains: there were fragments of burnt wood but also fruits and seeds from forest trees like

jutai, achua, brazil nut and various palms, that still grow in the Amazon rainforest today. Radiocarbon dating of the carbonised

plant, as well as luminescence dating of burnt stone tools and sediment, placed the early occupation of the cave at around

13,000 years ago.

1

,

2

Intriguingly, the chunks of ochre found in the archaeological layers were similar in colour and chemical composition to the

pigment in the paintings on the wall of the cave. It’s impossible to know for sure, but those paintings

could

have been made by the palaeoindian cave-dwellers 13,000 years ago.

Some scholars have argued that the rainforests of Central and South America would have constituted an ecological barrier to

colonisation by palaeoindians (a strange contention really, given that we know people were living in the rainforest at Niah

at least 40,000 years ago, and probably much earlier). And Pedra Pintada definitively demonstrates that this is a misconception:

palaeoindians were happily living in the late Pleistocene rainforest.

3

The further importance of Pedra Pintada to theories of the colonisation of the Americas is that it demonstrates that there

were people living in the Amazon Basin at the same time as (or possibly earlier than) Clovis people in the plains of North

America, but more than 5000 miles to the south.

1

As these two cultures were contemporary, this is clearly a problem for the ‘Clovis first’ theory. There

must

have been people in the Americas before Clovis. Long before Clovis, in fact, as my last destination would prove.

I caught the boat back to Santarém, and made my way to the airport, where clouds of lemon-yellow butterflies were still streaming

across the runway. Then I left the tropical warmth of Brazil behind me as I headed south, to Chile in mid-winter.

Black Soil and Revelations: Monte Verde, Chile

It was quite a shock stepping off the plane in Chile, into a grey, chilly winter’s day. I was a long way from the vibrant

colours and warmth of the tropics, and I was back on the Pacific coast.

It was so cloudy when I arrived in the small city of Puerto Montt that I couldn’t see the amazing setting I was in: a landscape

of lakes and volcanoes. Later, when the clouds lifted, I started to make out the snowy slopes of Osorno and Calbuco in the

distance.