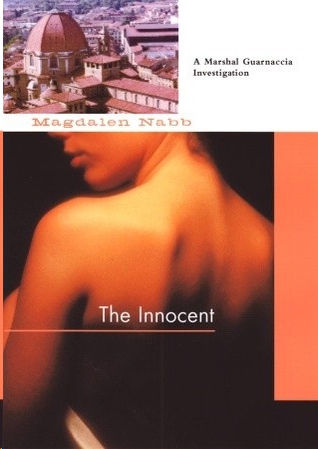

The Innocent

Also by Magdalen Nabb

Property of Blood

Some Bitter Taste

The Monster of Florence

The Marshal at the Villa Torrini

The Marshal Makes His Report

The Marshal’s Own Case

The Marshal and the Madwoman

The Marshal and the Murderer

Death in Autumn

Death in Springtime

Death of a Dutchman

Death of an Englishman

with Paolo Vagheggi

The Prosecutor

Copyright © 2005 by Magdalen Nabb and by Diogenes Verlag AG Zurich

Published in the United States in 2005 by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Nabb, Magdalen, 1947-

The innocent / Magdalen Nabb

p. cm.

ISBN-10: 1-56947-414-1

ISBN-13: 978-1-56947-414-3

eISBN-13: 978-1-56947-761-8

1. Guarnaccia, Marshal (Ficticious character)—Fiction. 2. Young women—Crimes

against—Fiction. 3. Police—Italy—Florence—Fiction. 4. Japanese—Italy—Fiction.

5. Florence (Italy)—Fiction. 6. Rome (Italy)—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6064.A18I565 2005

823’.54—dc22 2005059094

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

I

t was one of those perfect May mornings, hot and fresh, with a sky that was paintbox blue. Even if he’d known what was going to happen, the marshal would have found it impossible to believe at that moment.

Lorenzini had tried to stop him on his way out. ‘Don’t you want a driver?’

‘No, no. It’s as quick to walk …’

And he had escaped from his Station, eager to be out. He could hardly explain to Lorenzini, his second in command and as down-to-earth a Tuscan as you could hope to meet. The thing was that, as soon as he’d opened the window in his little office and sniffed the sunshine, he’d known it was one of those mornings. The Florentines would be tuning up for the day with the maximum of noise and fuss. He emerged from the cool shadows of the stone archway into the dazzling light of Piazza Pitti, fishing for his sunglasses and, dead on eight o’clock, the conductor raised his baton. Hammers began ringing on scaffolding going up against the façade of the Pitti Palace, clanging away in time to a dozen tuneless church bells. Horns tooted as the first traffic jam of the day formed below the sloping forecourt around some roadworks. A pneumatic drill started up.

‘Marshal Guarnaccia! Good morning!’

‘Oh, Signora! Good-morning—how’s your mother doing?’

‘She should be out of hospital tomorrow. Mind you, we can’t expect …’

What it was we couldn’t expect was drowned out by the roaring drill and the marshal, with a vague, inaudible answer, pushed between the queuing cars and made for the bar on the other side of the piazza.

The bar was full of people having breakfast and the hissing espresso machine sent up wafts of fresh coffee. Three women, in summery outfits, stood blocking the counter, deep in discussion.

‘Don’t get me wrong, I’ve got nothing against her. She’s good woman, she’s delightful, she’s a saint, whatever you want! But she’s a megalomaniac, that’s all I’m saying!’

The marshal removed his sunglasses and stared at the speaker. She wore a lot of jewellery and looked as if she’d just been to the hairdresser, which she couldn’t have at that hour, could she … ? Over her head the barman indicated that he was already making the marshal’s coffee.

He shifted away from the women’s perfume in favour of hot jam and vanilla. It might have been the pleasure of the spring morning or it might have been those two bits of dry toast which were his breakfast these days, but he helped himself to a warm brioche and that was that.

‘Of course, she means well.’

‘Oh, of course!’

What a conversation! The marshal drank up his coffee and paid.

He couldn’t get out of the bar because of an unruly snake of schoolchildren pushing and yelling, tumbling along the narrow pavement. A woman trying to get in lost her temper. ‘They’re allowed to run riot these days. It’s disgraceful!’

Retreating behind his dark glasses, the marshal remained silent. If they couldn’t run riot at that age, when could they? He was well aware that the sight of his uniform inspired people to blame him for just about everything, from undisciplined schoolchildren to the war in Iraq, not to mention that broken street light which, no doubt, would get mended now the elections were coming up. He joined the tail end of the school group moving towards via Guicciardini and the Ponte Vecchio. Their accents were northern, must be a school trip … People regarded him as one of the ‘they’ who ‘ought to do something about it’. A large, pink-faced man was coming towards him, shifting on and off the kerb between pushing children and hooting cars, and trying to shake off a whining gypsy woman who was pulling at his clothes. The marshal paused and turned his black gaze on the gypsy who disappeared to attach herself and whine elsewhere. Well, it was true. They ought to do something, but what … ? That fat schoolboy at the back whose friends were jumping on him and snatching at his backpack might have been his older son, Giovanni. Totò, younger, livelier and cleverer, ran rings round him. Giovanni, so like his father, had all his sympathy, Totò his admiration.

He paused again. A pretty shop assistant emptied a bucket of soapy water on to the uneven flagstones in front of a leather shop and swept the suds into the road.

‘Sorry …’

‘No, no … Take your time.’ He enjoyed the smell of the leather on the warm air. The girl smiled at him and went in with her bucket.

The children had pushed on, and were cutting a swath through the tourists on the bridge, while the marshal turned away from noise and sunshine into the gloom of an alley to his left.

He always chose this route for cutting through to via Maggio and the big antique shops these days. Traffic had been banned from going through, so he could walk in the middle and hear his own footsteps on the uneven paving, above the other sounds of hammers and rasps, radio music and snatches of conversation. Exhaust fumes had been replaced by the old familiar smells of glue and varnish, fresh sawdust and drains. And just about at the halfway point between the two main streets, four of these alleys met in a tiny piazza. It was a higgledy-piggledy sort of shape and for most of its short life it hadn’t even had a name. Recently, the residents had chosen one and put up a plaque they’d had made themselves. The reason for this was that the piazza had been created not by a Florentine architect but by bombs and landmines during the German retreat.

Luftwaffe

pilots, ordered to bomb the Ponte Vecchio, took very good care to miss it. The result of their excursions was the destruction of the buildings on either side of the bridge and the creation of this ‘piazza’ where a building at the crossroads had been mined to block the roads leading to the only surviving bridge over the Arno. It had quickly taken on the air of the real thing and filled up with restaurant tables and potted hedges. Fluttering from windows and brown shutters hung rainbow flags for peace, violet flags for the Fiorentina and fresh white flags for the medieval football tournament which would start in a few days.

‘Morning, Marshal! How’s it going?’

As usual, Lapo was on the doorstep of his little trattoria, grinning defiantly behind huge glasses across his four chequered tables at the grander twelve-table outfit a few metres away. His hands were stuffed under the bib of the apron down to his ankles such as his father and grandfather had worn before him. The sleek young things across the way wore trendy imitations of the same.

‘Can’t complain, Lapo. How about you?’

‘Not so bad, not so bad. Have a coffee with me.’

‘No, no … I’ve only just had one. I must get on.’

‘So when are you going to come and eat with us? You’re always saying you will. My Sandra’s a good cook, you know.’

‘I’m sure she is …’ The good smell of herbs and garlic sizzling in olive oil, as she started her sauce for today’s pasta, wafted from the open door.

‘You’d be my guest, you know that.’

‘It’s not that …’

‘No, well, I didn’t suppose it was, not with the prices I charge. If you’re thinking of eating across there you’ll be wanting a mortgage.’

‘I would never dream of going there, you can be sure of that.’ The thing was that after years of being a grass widower before his wife joined him from Sicily, the last thing he wanted was to eat out anywhere. Going home to his own kitchen and finding family, food and warmth was his idea of luxury.

As if reading his mind, Lapo insisted, ‘Bring the wife and kids.’

‘I will. That’s a promise. Now, I’d better be on my way. How’s it going with …’ The marshal inclined his head to indicate the bigger restaurant. ‘Are they still trying to buy you out?’

‘Oh-ho, yes.’ Lapo smiled broadly, flashing a row of shiny new teeth of which he was very proud. ‘You can’t imagine the amount of money they’re offering, it’s unbelievable! They’ve even told me to name my own price—there he is now.’ The young owner appeared on his doorstep, black hair sleeked close to his head, black T-shirt, long green apron.

‘Look at that suntan, eh, Marshal? He shut for two weeks in March to go skiing. The people I serve, work. I shut when they shut. What does he think I’d do with his money? Where would I go? This is not a job, it’s my life, here with these people.’ He waved a hand to include the packer who parcelled up bronze chandeliers and pieces of marble statuary for shipping abroad, the shoemaker, the furniture restorer and the printer. ‘Of course, he’s from Milan. You know the sort. They know the price of everything and the value of nothing. Well, he’ll find me a tough nut to crack. I’m enjoying myself, to tell you the truth.’ Lapo grinned and waved a cheery hand.

The younger man nodded and smiled, ‘Good morning!’

Lapo shoved his hands back under the bib of his almost clean apron and muttered, ‘I’ll good-morning you, arsehole—you don’t know what it means to have been born in this Quarter but you’ll learn. What do you say, Marshal?’

Guarnaccia laid a big hand on the smaller man’s shoulder and said, ‘You stick to your guns. It’ll be all right …’ He hoped he sounded more convinced than he felt. As he walked on past the swishing of a printing press behind dusty frosted glass and the cool, fruity smell of ink, he wondered about Lapo, about all of these Florentines. He’d lived among them for so long, but every now and then he would get the feeling that they were from another planet. The young furniture restorer wasn’t there. His shutter was down. He was often away up north, buying stuff. The shoemaker wasn’t there either, though the door was open and the spotlight over his last was switched on.

A young boy was working there, head bent low in concentration. Must be an apprentice. Yet weren’t they all forever grumbling that it was impossible to get apprentices these days … ? Captain Maestrangelo, his commanding officer, always smiled at the marshal’s puzzlement, and it took a lot to get a smile out of him. Once he’d said:

—The world is made up of five elements: earth, air, fire, water, and the Florentines.

The marshal had stared at him, not knowing what to reply.

—Not my own, I’m quoting.

—Ah …

What was that supposed to mean? He should have asked Lapo about the shoemaker, a prickly, sharp-tongued man. His handmade shoes were famous all over the world, his quick temper a byword in the piazza. He’d had a heart attack last year and the doctor had ordered him to take it easy, not get so annoyed. Nobody, including the marshal, thought much of his chances.

He came out on via Maggio and started his round of visits to the important antique dealers, delivering this month’s list of stolen pieces. Lorenzini had by this time given up saying:—We could send them e-mails. Probably he considered the marshal, who still prodded with two fingers at his manual typewriter, a hopeless case. It could be, though, that with experience he was beginning to understand that when a crime was committed it was too late to start getting to know your people.