The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (33 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

The Taxis also had their difficulties in these years. The division of the Habsburg inheritance between Spain and Austria compromised their existing contracts as imperial postmasters, and led to legal and jurisdictional problems. The imperial post had to this point been paid for by the Netherlandish treasury, underwritten by Spanish subventions. When Philip II inherited the Netherlands, the service became de facto Spanish. This in itself was sufficient to alarm the German postmasters, since a number of those appointed to man the local stations were Protestants. In 1566 two members of the Taxis clan, Leonhard the general postmaster, and Seraphin, postmaster of Augsburg and Rheinhausen, actually embarked on litigation with each other to resolve a dispute over the division of fees along the Netherlandish/German road.

23

That the payment of the postmasters’ salaries depended on Spanish subventions became increasingly critical when the Spanish treasury ran out of money. Spanish bankruptcy meant that salaries went unpaid. The system began to creak. In 1568 Cardinal Granvelle was already complaining of stoppages and major delays. A decade later the German postmasters could stand it no more; in 1579 they went on strike.

For the German Lutherans the patent inadequacies of the imperial postal service in this period represented something of an opportunity. The leading princes established their own messenger relays. In 1563 Philip of Hessen and August of Saxony joined together to sponsor a courier service to keep them in touch with William of Orange, a vital ally in the Netherlands.

24

Later Württemberg

and Brandenburg-Prussia would be brought into the network, though it remained essentially a private system of communication between the German Protestant courts, not open to the public.

For the imperial cities, the motivation was more commercial than political. For some time a single arterial network that privileged official government mail had not suited their needs particularly well. In 1571 the merchants of Nuremberg petitioned for the establishment of a direct link with Antwerp via Frankfurt and Cologne. The following year Frankfurt established its own weekly postal service to Leipzig. These

Ordinari-Boten

were the descendants of the fifteenth-century city messengers. The difference was that the system would, like the imperial post, be open to all, and would follow a regular published timetable.

The 1570s witnessed the establishment of a dense network of these city courier services throughout Germany.

25

The northern city of Hamburg had previously laboured under a significant disadvantage through its distance from the main postal routes.

26

Now, starting in 1570, the city created a whole postal network of its own, with weekly services to Amsterdam, Leipzig, Bremen, Emden, Cologne and Danzig. The influence of the Netherlandish Protestant diaspora is evident in the choice of routes, since many of these cities (Hamburg included) had significant colonies of exiled Dutch merchants. Even in privileged Augsburg the merchants saw which way the wind was blowing. In 1577 they established their own independent merchant post to Antwerp via Cologne.

27

The Augsburg postmaster, Seraphin von Taxis, was understandably furious at this apostasy, but while the imperial post was in chaos there was little he could do. This same year the general postmaster Leonhard was forced to flee Brussels to avoid being imprisoned by the Dutch rebels. The situation could not go on, and in the last two decades of the sixteenth century the Emperor himself intervened to take matters in hand.

Regeneration

The reform of the post became the rather unlikely crusade of Emperor Rudolph II, who had succeeded his father Maximilian II as ruler in the Habsburg dominions in 1576. In his last years Rudolph would become a tragic figure, self-exiled to his castle in Prague with his ever-expanding collection of curiosities. But even Rudolph could see that the brewing crisis of religion in the imperial lands required closer coordination of imperial Habsburg policy. The result, in 1597, was a milestone edict reforming the imperial post.

28

This mandate proclaimed the reunification of the Spanish and imperial systems and simultaneously announced stern measures against unauthorised

competition. If this had the urban courier services in its sights, it was bound to remain a dead letter while the imperial postal routes provided no service for the major German cities. In 1598 therefore the imperial post took a major step forward with the establishment of an imperial post office in Frankfurt, with a branch line linking Germany's main commercial marketplace to the existing network. An entirely new post road then connected Frankfurt directly with the Netherlands via Cologne. After protracted negotiations a new east–west service was created between Cologne and Prague, via Frankfurt and Nuremberg. Finally a direct service between Cologne and Hamburg, and between Frankfurt and Leipzig, brought the principal cities of the north and east into the system.

29

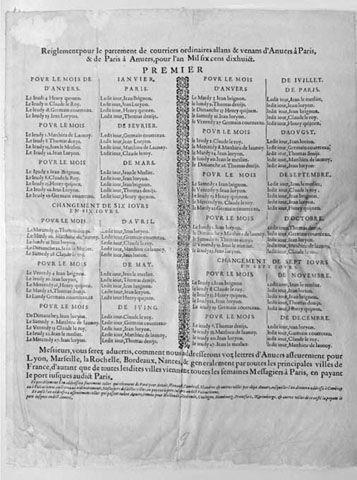

8.2 The postal service between Paris and Antwerp, five times a month in both directions. This was a vital lateral route, connecting two major news hubs and through them the Low Countries and provincial France.

All this was not achieved without a certain amount of bad blood. Having invested in their own regular courier services, the German cities did not take lightly to their prohibition. An arrest of city couriers on the road between Frankfurt and Cologne led to a collective protest to the Emperor.

30

But the imperial post had one critical advantage. The new imperial routes were set up with the same sequence of relays as the main imperial line. The city courier services, in contrast, had no intermediary stages for changes of horses: the couriers rode the whole length of the route. In direct competition the imperial service could often deliver the mail on the longer journeys in half the time. As tempers cooled, the German city councils recognised the benefits of the imperial system and the independent German courier services gradually withered away.

By 1620, at the conclusion of these developments, the German Empire had been provided with a postal system of unparalleled efficiency and sophistication. The single arterial route between Brussels and Vienna had been replaced by an intricate network of services centred on Germany's new postal capital, Frankfurt. Taken together with simultaneous renovations in the English and French systems, the revitalised imperial post made possible a new era in the history of communication.

The new imperial postal network reached its completion just as the long period of peace enjoyed by Germany since 1555 was about to come to an end. In 1618, two years after the announcement of the new Frankfurt–Leipzig line, the Defenestration of Prague began the tragic sequence of events that made Germany the new battlefield of international politics. The Thirty Years War brought death and destruction to large areas of Germany, as foreign and mercenary armies criss-crossed the Continent. The conflict caused terrible damage to the Germany economy, and ended for ever German supremacy in parts of the European book trade. But one perverse consequence was to give new impetus to the development of an effective international postal network. The involvement of so many foreign powers in the German conflict meant that all Europe's capitals felt the need for swift, reliable information. Several took steps to improve their own internal communications, and to link these systems to the central European postal network. In France the royal postal monopoly was strengthened, and the network of postal stations expanded in 1622 to take in the southern cities of Bordeaux and Toulouse, and also Dijon, close to the potential battlefields in the east. In this same year Lamoral von Taxis established a courier service between Antwerp and London. This was followed, a decade later, by a treaty between the Brussels postmaster and the English postmaster general.

31

Danish and Swedish interests in Germany also stimulated an improvement in the information network.

32

In 1624 Christian IV of Denmark set up his own

postal system, based on Copenhagen, with a branch office in Hamburg. Four years later the Swedes extended this network with their own connection between Hamburg and Helsingör. The Swedish invasion of Germany in 1630 briefly resulted in the creation of an alternative postal network centred on Frankfurt, with 9 routes and 122 posts.

33

While this soon collapsed after the Swedish defeat at Nördlingen in 1634, a more enduringly significant development was the establishment of a direct route between Paris and Vienna, via Strasbourg, finally cutting out the long diversion through Brussels that had so limited French access to the international post.

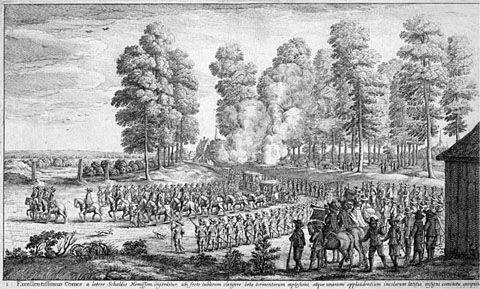

8.3 The profits of a postal monopoly. Part of a series of four prints commemorating a visit by the Imperial Postmaster-General, the Count Thurn and Taxis, to the Postmaster of the Netherlands. The size of the retinue is impressive.

With this development, the European postal network was fundamentally complete. The only further innovation that would be introduced, really until the coming of the railways and the penny post, was the substitution of a coach service in place of the postal riders.

34

The postal coaches increased the volume of mail that could be carried, and created the possibility for travellers to avail themselves of the service. In the sixteenth century merchants and messengers who had ridden post had to be able to ride at the speed of the postal riders. This was an expensive service and only men who rode well could consider it. The postal coaches were a different matter; from the mid-seventeenth century, when coaches started to appear on short stretches of the German roads, a far

wider cross section of travellers could avail themselves of the opportunity to travel in comfort. No longer did a traveller have to furnish their own wagon, ensure that the horses were strong and sound, and check that the driver was equipped to make what repairs were necessary on the journey: all that would be taken care of. Regular timetables meant that travellers could plan a journey with the reasonable assurance of timely arrival. The extra carrying capacity was especially important for the distribution of bulky mail items, such as newspapers. Within a few decades of their establishment the mail coaches came to bear the major burden of the timely distribution of printed news.

The developments we have witnessed in this chapter represent a remarkable advance in European communications. The previous centuries had seen slow incremental changes in the rates of travel, accompanied by an increase in the volume of correspondence between those with sufficient funds to create their own network of communications. The best news was available only to those who could make the considerable investment necessary for what were essentially private networks, official or commercial. The coming of print in the sixteenth century had brought with it a substantial transformation in the reader community, and ingenious innovation in printed news: though much of this news was not particularly fresh, or, indeed, time specific. All of this changed within two decades of fierce innovation at the turn of the seventeenth century. At their end all of Europe's major commercial centres were closely linked in a dense web of public postal services. News could now be passed along reliable channels, at modest cost, with far greater regularity. It is no surprise, therefore, that the next significant development in the commercial exploitation of this news should take place here, in the commercial hubs of Germany and northern Europe. This development, closely connected with the expansion of the postal service, was the birth of the newspapers.

CHAPTER 9