The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (47 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

The same potent combination of observation and imagination can be observed in the astonishing interest shown in what were known, in the unforgiving terminology of the time, as monstrous births.

15

Conjoined twins were a fascination of the age, and were captured in images often of great anatomical precision. We are likely to give less credence to reports, chronicled with equal earnestness, that a woman had given birth to a cat. But these reports were treated with the utmost seriousness by sixteenth-century authorities, not least because they were thought to portend shocking and evil consequences. No less an authority than Martin Luther achieved an enormous success with the so-called monk calf, a tonsured half-beast he presented as an allegory of the corruptions of the Catholic priesthood.

16

The birth of conjoined twins was universally accepted as a judgment on the sins of the parents. As a broadside of 1565 argued, the ‘monstrous and unnatural shapes of these children are not only for us to gaze and wonder at’. The births of such children ‘are lessons and schoolings to us all who daily offend … no less wicked, yea many times more than the parents of such misformed’ children.

17

And when, in 1569, the English Privy Council received reports of the woman who had given birth to a cat, they ordered one of their number, the Earl of Huntingdon, to investigate. Huntingdon was shortly able to send Archbishop Grindal a detailed transcript of the alleged mother's interrogation, complete with an illustration of the cat.

18

Having reviewed the evidence Grindal decided that this was a hoax, though it was never really established why it had been perpetrated. What is clear is that the event was not regarded as necessarily fantastical; a considerable amount of time was expended by senior officials in flushing out the truth.

This is the part of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century news world that must seem to us most foreign. We are hard put to believe that women gave birth

to animals, or that the inhabitants of Sussex had been terrified by a dragon; yet such reports were published in pamphlets and newspapers right up to the eighteenth century.

19

Sudden calamities and afflictions prompted particular reflection: in this era all news had a moral shape. Victims of misfortune, particularly collective misfortune, were always invited to look to themselves for causes.

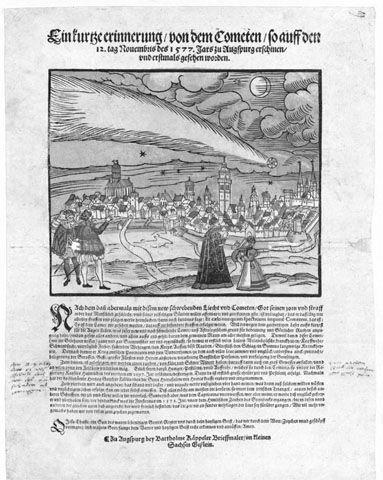

12.1 The comet of 1577. A frequent subject for representation, and feverish interpretation.

The sense that calamitous events represented the working out of God's purpose was still unflinchingly believed throughout this period. We see it in the Protestant reporting of the sack of Magdeburg, which highlighted both the horror and the need for God's people to turn back to Him with a humble spirit.

20

Incidences of plague, a recurring terror of these centuries, prompted a similar call for amendment of life. This was an affliction that seemed to defy both treatment and cure, striking indifferently at rich and poor. A stunned sense of powerlessness is as evident in pamphlets written at the time of the London plague in 1665 as it had been a century before. Plague was, in the Dutch expression, God's gift, beyond the fathoming of medical science.

21

The plague was beginning to recede when in 1666 London was consumed by a devastating fire. In this case renewed reflections on God's dreadful justice were mixed with more prosaic analysis: rumours quickly circulated that the fire had been deliberately started by the Catholics.

22

This shift in emphasis, certainly encouraged by the increased level of news reporting, marks a trend towards a more rationalistic turn to the reporting of natural and man-made disasters. It coincides with the increased dissemination of empirical observation in the natural sciences. Scholars were encouraged, and encouraged each other, to gather and interpret empirical evidence, and be less respectful of inherited wisdom; as science advanced, so God's domain would contract.

23

Applied to the world of news reporting this shift in emphasis certainly had a darker side. For as news men gradually abandoned the pious calls for self-amendment, they focused instead on a new avenue of causality: if they were not to blame themselves, then blame must lie elsewhere. A ravenous news press fed and encouraged the search for scapegoats, and a heightened adversarial tone to political debate. In this respect, at least, news reporting became recognisably more modern.

News Well Buttered

The question of how much credit should be given to news reports was of course as old as news itself. It underlay all the calculations of rulers of medieval societies, as they weighed the value of the limited and incomplete sources of information at their disposal. But at least in earlier generations these problems had been relatively well defined: How much could one trust a messenger? Was the bringer of news an interested party? How much weight to put on a rumour? Necessarily, until recipients of news could obtain corroboration, much consideration was given to the credit of the bearer, who might be a trusted subordinate, a well-informed source who had provided good information before, or a correspondent whose integrity guaranteed straight dealing.

News reposed on the same bedrock of trust and honour that in principle underpinned all relationships among those of a certain social standing.

24

This comparatively intimate circle of news exchange was significantly disrupted by the birth of a commercial news market. The market for news spread beyond those for whom it was a professional necessity to be informed, to new, more naïve and inexperienced consumers. The intensification of pamphlet publication and the first generation of newspapers also coincided with a series of complex international conflicts which generated a large but dispersed audience eager for the latest intelligence. It was inevitable that this new hunger for news and the commercial pressures to satisfy it led to the reporting of much that could not be verified, and some downright invention. In 1624 the young dramatist James Shirley wrote scathingly of the trade in fabricated tales from the battlefield, penned by men who had never been near the front. ‘They will write you a battle in any part of Europe at an hour's warning, and yet never set foot out of a tavern.’

25

If there was money to be made, Shirley implied, the newspapers would print it.

This was not altogether fair. Shirley's observations were made at the height of the Thirty Years War, a critical but difficult era for news reporting. People all over Europe were desperate for the latest intelligence; but as we have seen the destruction caused by the fighting created severe disruption to the channels of information flow. Partisan hopes and fears made for additional distortions. The new generation of serials during the English Civil War faced similar problems with their domestic reporting, as William Collings, editor of the

Kingdom's Weekly Intelligencer

, wearily acknowledged in 1644. ‘There were never more pretenders to the truth than in this age, nor ever fewer that obtained it.’

26

As this example makes clear, news men were very conscious of the difficulties they faced in getting true reports. Thomas Gainsford was one of several who used his columns to urge readers to be less impatient: news could not be printed if there were none to be had. News men had no wish to be bounced into publishing information that turned out not to be true, not least because their livelihood depended on a reputation for reliability. William Watts was badly wrong-footed when after the battle of Breitenfeld in 1631 he reported the death of the Catholic general Tilly, and held to this even when reports emerged to the contrary. We can appreciate, though, that his reasoning did reflect a careful attempt to balance conflicting information. Watts just guessed wrong:

Indifferent reader, we promised you (in the front of our last Aviso) the death and internment of Monsieur Tilly, which we now perform: notwithstanding the last Antwerpian post hath rumoured the contrary, against which you may balance each other, and accordingly believe. Only we will propose one question

unto all gainsayers, let them demonstrate where Tilly is, and that great formidable army which he has raised, and we will all be of the Catholic faith.

27

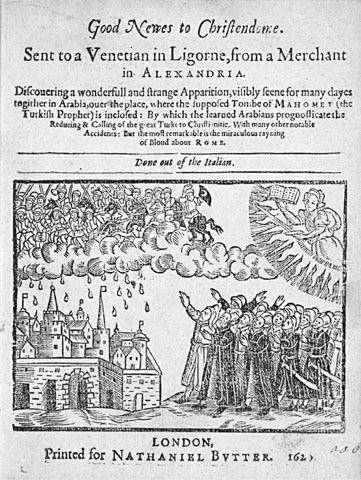

12.2 Unquiet skies. Here Butter has both armies battling in the sky and clouds dripping blood. A strange apparition indeed.

In fact, instances where a news man would go out on a limb with an unconfirmed rumour were rare (and there is no evidence that Watts followed through on his pledge to turn Catholic). Seventeenth-century newspapers

were on the whole characterised more by caution than risk-taking. Many news men were at pains to point out when foreign news was as yet unverified. Gainsford's judicious formula could stand for many: ‘I would rather write true tidings only to be rumoured, when I am not full sure of them, than to write false tidings to be true, which will afterwards prove otherwise.’

28

This professionalism was seldom credited by the critics of news men. Much of the criticism of newspapers, it must be said, emanated from privileged members of existing circles of news exchange, like James Shirley, and the proprietors of manuscript news services who had a financial interest in emphasising the superiority of their own sources. The ridicule heaped on the newspapers and their readers also reflected a decree of social contempt for neophyte consumers. Nowhere was this more evident than on the London stage, where dramatists made the newspapers a regular butt of their humour. The unfortunate Nathaniel Butter came in for particular ridicule, as his name proved an irresistible target for puns. In

A Game of Chess

, Thomas Middleton made great play of Butter, presumably knowing that for his audiences Butter was the public face of news. Abraham Holland concluded a more general assault on the news men with a memorable couplet:

To see such Butter every week besmear

Each public post and church door!

29

The news men's principal persecutor was Ben Jonson, the first to make the newspaper press the subject of their own play,

A Staple of News

. Here the target was as much the credulous purchasers of news as the news men, like the countrywoman whom Jonson imagines wandering into the staple office to ask for ‘any news, a groat's worth’.

30

Such simpletons, he implied, were easily manipulated. The criticism was probably wide of the mark. Although in principle a single issue of the news serial was well affordable for many of very limited income, these were not the typical consumers of news serials. The news men aimed their productions at a subscription market: and subscribers were likely to have been wealthier (a shilling a month was a significant outlay) and more sophisticated readers; they would need to be, to make sense of the elliptical, staccato reports that were the newspaper style.

One should also keep in mind that sceptical commentators usually had an axe to grind, and the London playwrights were no exception. To some extent the newspapers threatened the theatre's role in contemporary news commentary. Ben Jonson was a representative of the established media, enjoying the access of the privileged to information and backstairs gossip. He had smoothly mastered the theatre's arch references to contemporary events

for an informed and knowing clientele. He also disapproved of the news-papers’ editorial line: he was no supporter of the policy of intervention in the Thirty Years War. He resented the papers’ political role, which by raising consciousness of the plight of Protestants abroad piled pressure on the reluctant king to intervene.