The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (48 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

So Jonson, like many representatives of the established media, was never likely to give the newspapers a fair hearing. Even so, his criticism does reflect a wider dissatisfaction with the serial form itself – and here there were fair points to be made.

31

Until this point the pamphlet had been the normative printed form of news delivery. Although news pamphlets and serials shared many points of similarity (the serials were closely modelled on the pamphlets in physical terms), their relationship with the potential audience was fundamentally different. Non-serial pamphlets were very much superior as conduits of information. Because they only appeared when there were important events to publicise, they did not have to deal with uncertain or unresolved issues: they were published after the event. On the whole they had much more space (on average four times as much text as early newspapers) and dealt with a single issue rather than the newspapers’ frantic miscellany. Because non-serial pamphlets were one-off publications they did not assume prior knowledge; they took time to explain context and consequences. The news events recorded in pamphlets often preserved their interest for some time. Many were published or reprinted a long while after the events described. They did not need to be rushed out; they left time for reflection and judgement.

The news serials were invariably more hectic. They described events still unfolding, and not yet fully known. They were forced to include much information that seemed portentous at the time, but in retrospect was utterly trivial. The news men, whose major editorial task was to choose what threads of news to print from a larger heap, were not particularly well qualified to make such judgements. Often this was just one of many tasks in a busy print shop. No sooner was one issue on sale than news men were gathering copy for the next. There was little mental space for reflection and explanation, even if the style adopted in the newspapers (inherited from the manuscript newsletters) had allowed for this, which it did not.

News pamphlets could adopt a very different approach. Most pamphlets would appear only at the conclusion of a siege or campaign, when the outcome was known (a luxury not available to a weekly publication). In a pamphlet facts could be marshalled and shaped towards this known outcome. For those wanting to make sense of troubled times this must have seemed a much more logical form of news reporting. Pamphlets also offered more opportunity for erudite and fine writing, for commitment and advocacy.

So there were good reasons, quite apart from professional competition, why many regarded the newspapers as a fad, and a retrograde step for news publication. But when Ben Jonson took aim at the new naïve readers, he need not have worried, because these were hardly the intended audience: these neophyte consumers were far more likely to buy, if anything, a pamphlet which gave them a complete view of a single subject. An individual issue of a newspaper would always be like coming into a room in the middle of a conversation; it was hard to pick up the thread, and the terse factual style offered little help. This was not how they were intended to be read, or collected: most newspaper issues passed safely into the hands of more sophisticated readers, who followed events on a regular basis.

The Scourge of Opinion

The rising tide of criticism reflected the fact that by the late seventeenth century a serial press was a fixed and unavoidable feature of the commerce of news. While the lands in northern Europe had taken most enthusiastically to the newspapers, by late in the century Italian cities also had a decent scattering of papers, and the form was even beginning to establish a foothold in Spain. Germany, with its patchwork of independent jurisdictions, achieved by far the best coverage, and it was here too that the critics of newspapers made their voices heard. In the third quarter of the seventeenth century a number of writers articulated their disquiet at the proliferation of the serial press, and the dangers to society if newspapers fell into the wrong hands. In 1676 the court official Ahasver Fritsch published a brief pamphlet on the use and abuse of newspapers.

32

Fritsch was a firm supporter of princely power, and was strongly of the view that the circulation of newspapers should be confined to public persons who had an occupational need to remain informed (that is, the traditional readers of

avvisi

). The fact that he published his tract in Latin indicates that these were very much his intended audience.

Fritsch's theme was taken up a few years later by Johann Ludwig Hartman, a Lutheran pastor and prolific author. Hartman had developed a line in sermons denouncing the sins of dancing, gambling, drinking and idleness; to these he added, in a trenchant discourse of 1679, the sin of newspaper reading.

33

Hartman was prepared to concede that merchants needed to read newspapers; but otherwise they should be forbidden to the general public. Fritsch and Hartman set the tone for a debate that focused on defining which social groups could safely be entrusted with political news. Daniel Hartnack, a skilled and imaginative publisher, also tried to draw a distinction between useful reading and mere curiosity. In normal times, Hartnack agreed, reading of newspapers should be restricted to the informed who could apply proper critical judgement. Only in time of war should everyone read papers.

34

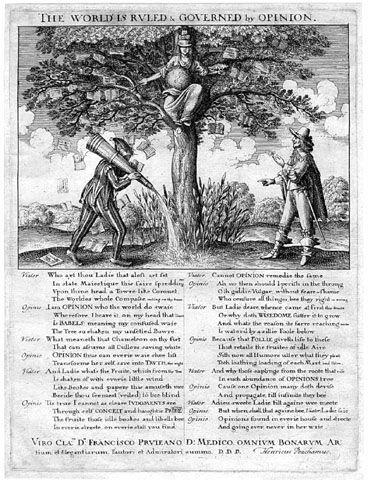

12.3

The world ruled and governed by opinion

. Opinion is represented as a blindfolded woman, crowned with the Tower of Babel. The fruits of the tree are pamphlets.

This sense of social exclusivity is a warning against overestimating the reach of the first generations of newspapers. Those in the circles of power, with access to good sources of news, were deeply sceptical as to whether much good would come of extending these privileges to untrained minds. It was only at the very end of the seventeenth century that a German author would join the debate with an unambiguous statement in favour of reading newspapers. Kaspar Stieler's

Zeitungs Lust und Nutz

(

The Pleasure and Utility of Newspapers

) was a ringing endorsement of the right to follow the news:

We who live in this world, must know the present world; we get no help here from Alexander, Caesar or Mohammed if we wish to be wise. Whoever seeks this wisdom and wishes to partake in society must follow the papers: must read and understand them.

35

Stieler had no patience with the attempt to limit access. All people, he believed, had the natural instinct to learn, and this extended to the latest current events. By enumerating the groups that would profit from newspaper reading, Stieler answered critics of the press directly. Teachers and professors needed to follow the news to stay up to date. Clergymen could incorporate material from the papers into their sermons (and find in them instances of God's interventions in human affairs). Merchants and itinerant workmen would be informed of the conditions on Europe's hazardous roads. Country nobles read newspapers to ward off boredom, and their ladies should read them too: better they prepared themselves to discuss serious subjects than waste time on gossip. Those who objected that newspapers were full of material unsuited to gentle eyes should remember that the Bible was also ‘full of examples of murder, of adultery, of theft and many other sins’.

36

Stieler's broadside was timely, because at the beginning of the eighteenth century the virtues of news reading were far from universally acknowledged. On the contrary, the intensification of participatory politics brought a host of new anxieties that called into question the value – and the values – of the serial press. Critics of the newspapers focused on three main issues which they felt compromised the media contribution to public debate. They complained of information overload: that there was simply too much news, much of it contradictory. They worried that the old tradition of straight reporting was being contaminated by opinion. This they believed, not without reason, was because statesmen were seeking to manipulate the news for their own

purposes. All of these factors were likely to distort or obscure the truth, and leave readers confused and bamboozled.

The complaint that good sense was being drowned in a torrent of print was not entirely new at this time. Since the first decades of the sixteenth century, and the surge of pamphlets that accompanied the Reformation, contemporaries had been startled and unsettled by the pamphlet warfare stimulated by successive crises of European affairs. To apply the same criticism to the newspapers at the beginning of the eighteenth century may seem wide of the mark. In most parts of Europe a single newspaper still enjoyed a local monopoly. Only in London and a few German cities (notably Hamburg) was a larger number of regular serials in direct competition. Here rivalry could bring damaging consequences.

37

Papers were all too gleefully eager to point up each other's errors. It seems not to have occurred to them that by impugning their rivals they damaged the credibility of the genre as a whole. Daniel Defoe, who was hardly innocent of hyperbole or partisan exaggeration, at one time or another attacked the truthfulness or integrity of most of his competitors, including

The Daily Courant, The English Post, The London Gazette

,

The Post Boy

and

The Post Man

.

38

The Tatler

sneered intermittently at the contradictions and exaggerations of the press, concluding, with lofty hyperbole, that ‘the newspapers of this island are as pernicious to weak heads in England as ever books of chivalry to Spain’.

39

Partly this professional warfare was the consequence of a crowded market. London papers drew very largely on the same sources of information for the bulk of their copy, made up of news from abroad. The search for an original angle naturally gave occasion for some artful embroidery. This inevitably caused readers some perplexity, particularly if they read the same report in different places. As Joseph Addison expressed it, with characteristic elegance, in his

Spectator

:

All of them receive the same advices from abroad, and very often in the same words; but their way of cooking it is so different, that there is no citizen, who had an eye to the public good, that can leave the coffee-house with peace of mind, before he has given every one of them a reading.

40

Addison reproved the dangers of journalistic licence; but this largely commercial pressure to embroider news was greatly compounded by anxieties that news was deliberately framed to a partisan agenda. This, the scourge of opinion, was a concern that extended far beyond the crowded London market.

12.4 An attack on

The London Gazette

. The author may not have reflected that such an attack on the English paper of record did nothing to enhance the credibility of the medium as a whole.

Here it is important to remember the historical roots of the newspapers in the manuscript newsletters: a form of news reporting that valued unadorned fact almost to a fault. Those who subscribed to the

avvisi

and their print successors valued the total separation of news from the more discursive, analytical and frankly polemical style of news pamphlets. The fear that the serial news publications might be polluted by this parallel strand of news reporting was widespread and increasing in the early eighteenth century. The publication of what were in effect serial polemics in the English Civil War was an extreme case. But even the German newspapers could not be entirely oblivious to the loyalties of their local readership in times of war. By the early decades of the eighteenth century English newspapers were openly abusing each other for their partisan loyalties, as much as their inaccuracies. Even so, newspapers still by and large fought shy of explicit attempts to direct their readers’ opinions. The first leading article or editorial in a German newspaper was published in Hamburg in 1687, but this proved to be an aberration: a

product of a market where competing serials encouraged experimentation to win readers.

41

More typical was the high-minded declaration with which the editor of

The Daily Courant

addressed his readers in the first issue in 1702: