The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere (38 page)

Read The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere Online

Authors: Caroline P. Murphy

Tags: #Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #History, #Renaissance, #Catholicism, #16th Century, #Italy

If Isabella did not write to Felice directly, then Gian Domenico made sure Felice knew what had occurred. For Felice, Isabella’s behaviour served to end a friendship that had lasted over twenty years. She knew how wealthy the Gonzagas were. Their exploitation of the Romans in such a time of financial desperation was utterly despicable. Yet Isabella was too powerful and too useful a person, especially given the ravaged state of Rome, for Felice to be able to sever links with her entirely. However, while Isabella wrote to Felice as her ‘dearest sister’, Felice in return used the formal language of patronage which emphasized the distance she felt between them. In a letter she wrote to Isabella following the incident with the del Bufalo family, Felice revealed nothing of her personal life; nor was there any suggestion that she held any affection for Isabella. ‘My lady and benefactress,’ wrote Felice to Isabella in

1529

, ‘I must thank your illustrious ladyship for the order you sent out for possession of the church pension of Santo Stefano di Povi to be given to Maestro Vincentio Caroso, gentleman of Rome, who is my creature, and I would be most obliged if you would write to the priest and ensure possession is maintained for Maestro Vincentio...and with reverence I recommend myself to you. Your servant, Felix Ruvere d’Ursinis.’

10

Nothing in the tone of this letter suggests that Felice and Isabella shared a history, one that had once involved plans for Felice’s daughter and Isabella’s nephew to marry, or their daring escape from Rome. Felice would have preferred not to have to write to her at all. It was difficult for Felice to be in a position of obligation to Isabella, even if it was on behalf of another, when she was so accustomed to being the

patrona et benefatrix

. And while she enjoyed the peace and tranquillity of Fossombrone, she longed to return to the states that she governed.

The Imperial army vacated Rome in the autumn of

1528

. Many Romans waited not just for the soldiers to depart but for the plague to die down as well before they returned. Felice herself was unable to leave for Rome until the late summer of

1528

. She had to wait for more than disease to leave her city. She had the added disadvantage of being haunted by the spectre of Napoleone.

Freed from gaol in Castel Sant’ Angelo, her stepson, predictably, had taken advantage of the anarchic situation, as well as of Clement VII’s lack of power, to take full control of the Orsini estates. He had established Bracciano as his headquarters, from which he was fighting his own personal war against the Imperial army, primarily for personal financial gain. He even took to piracy, holding up Spanish ships on the Tiber. Napoleone’s activities drove the Imperial army, an unlikely ally for Felice, to launch an attack on him. She received a communication from a secretary, Giovanni Egiptio da Vicovaro, in July, informing her that Napoleone had been ‘broken, with the loss of forty horsemen’.

11

Undaunted, he went north, to serve as a mercenary soldier in the Tuscan revolt against Medici rule.

It was only at this point that it was deemed safe for Felice to consider leaving Fossombrone and finally returning to Rome. Napoleone had gone; the Imperial troops had gone; the plague was over, and a humiliated Clement VII had paid a vast ransom to Charles V to secure his return and peace in the city. In the same letter, Giovanni Egiptio informed Felice she would receive a licence from Pope Clement VII, allowing her entrance into monasteries that would offer her accommodation on her way back home. Mules were hired for the journey, although Felice was to prove tardy in paying for them. One Angelo Leonardo da Calli would be obliged to write to her a year later demanding

25

scudi

, a not inconsiderable sum, for the mule she rode when she left Fossombrone.

12

chapter 7

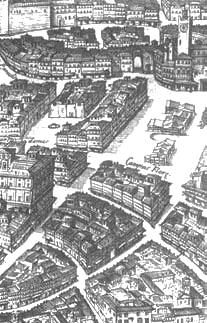

Felice rode on the hired mule into a Rome that was all but destroyed. The gleaming city created by her father, Julius II, had vanished. In its place were blackened buildings, such as the Palazzo Massimo, whose residents were now all dead. The remains of less opulent houses had been dismantled for firewood in the bitterly cold winter of

1527

. The population was decimated by violence and its aftermath, disease. Anybody looking at Rome could ask themselves, with good reason, how it differed from the city as it had been at the end of the Middle Ages. It says much for Roman resilience, a determination not to let the progress of the early sixteenth century be for nothing, that when its leaders did return, they immediately and effectively set to work restoring the prestige of their families and returning their city to its former glory. None the less, here and there, signs of the destruction can still be found. Underneath the beautiful pavement of Palazzo Massimo, rebuilt in the

1530

s by Baldessare Peruzzi, lie charred floor tiles, a memento of the time the palace was set alight in May

1527

.

Felice spent the next few years attempting to re-create her life as it had been prior to the events of May

1527

. There was much to be done, much to be replaced, from replacing clothing lost in the Sack to the repair of the badly damaged Orsini palaces. This period was not an easy one in Felice’s life and the events of

1527

had taken an emotional toll on her. Her servant Perseo di Pontecorvo wrote sympathetically to her in the August of

1529

, ‘I have heard that you are physically well, but that your soul is afflicted from these great troubles. I can say nothing but that I have the greatest sorrow for you, as well as for myself and that all we can do now is to be patient. I beg that you have the will to govern as well as you possibly can, with all your wisdom.’

1

However emotionally scarred Felice might have been, she had no option but to return to work, and there are indications that even if she was mentally depressed, she had no intention of entering into a physical decline. In the same month as she received the letter from Ponticorvo one of her woman servants, Camilla, wrote in response to Felice’s request for a teeth-cleaning recipe. Camilla’s instructions were to ‘boil rosemary with spring water, and with that, wash the teeth and gums every morning, then repeat, and this is the way to keep the gums healthy. To keep the teeth clean and white, take coral, pumice stone and radish and mix them into a powder, and in the morning rub them on to the teeth. Then take a bit of vinegar and wash it round your mouth, and this will make the teeth white and clean and refreshed.’

2

Felice also had a number of outstanding debts as a result of the Sack. She owed

4

scudi

to the mariner who had taken her from Ostia to Civitavecchia, although he had to wait until December

1531

to receive his fee. She needed a vast amount of new clothes for herself and her children. As her account book shows, a Roman merchant, Donato Bonsignore, did very well out of the family’s losses. ‘An authorization was made up for Bernardo de Vielli who has to give

50

ducats to Mr Donato Bonsignore, which is in part payment for the

105

ducats for the requirements created by the Sack of Rome.’ ‘An authorization was made for Donato Bonsignore to come to receive

20

scudi

for the many clothes Signora Felice wishes to take from the said Donato.’ ‘An authorization was made up for Donato Bonsignore, merchant in Rome, for

12

scudi

and

10

ducats,

12

scudi

to Mr Riccio, tailor, for the fabric taken by order of the Signora, which is for two yards and three palm lengths of raw silk to line a dress for Signora Clarice, and more to line and border two ladies’ dresses, and a

scudo

to Lorenzo Mantuano for a half-palm of scarlet silk for a stomach piece for Signor Hieronimo.’ ‘Two yards of satin and raw silk were taken from Donato Bonsignore for Signora Clarice’s under and outer garment for

5

scudi

.’ The greatest expense for a single item of clothing for Felice came in Jaunary

1532

, when ‘an authorization was made up for Bernardo de Vielli to pay Faustina de Cola da Nepe

20

scudi

to give to her husband in payment for the dress made of damask that he will make for Signora Felice.’

3

Rome was still experiencing severe food shortages. In March

1531

, Felice wrote a letter to Antonio da Corvaro, to whom she had written harshly in the months before the Sack, admonishing him for hiding a Roman fugitive. This time, however, she addressed him warmly as ‘mio amantissimo’, and thanked him profusely for sending a package of provisions to Rome: honey, chestnuts, and a barrel of snails.

4

The snails say much about the hardship of the time. Customarily the food of the poor, they were no longer to be scorned. Felice was actually in a more fortunate position than most when it came to access to food supplies, thanks to the grain grown on Orsini farmland, as well as her own harvest at Palo. The grain shortage in Rome was dire. Even before the Sack, grain reserves had been low. The Jubilee of

1525

had brought thousands of pilgrims to the city and they had demolished existing grain supplies. During the Sack, not only had the soldiers taken for themselves most of what was available, they had also fired much of the surrounding countryside, destroying young crops. In consequence, the price of grain rose exponentially and now cost as much as

20

ducats a

rubbio

.

5

The high grain prices operated to the advantage of those who had grain to sell. Indeed, the inflated price was the means by which Felice was able to bring about her family’s economic recovery. Her own servants had always received part of their wages in the form of grain, but it now became part of the payment given to outside help, such as Francesco Sarto, the tailor, who visited Felice’s home to sew for her. He received ‘one

scudo

and an authorization to go pick up a

rubbio

from Galera, on account of the sewing of the clothes he did for Signora Felice’.

6

And it was grain that helped Felice pay for the damage done to her Roman properties during the Sack.

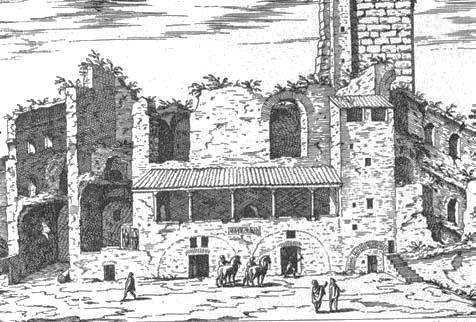

Despite her evident ambivalence towards the palace of Monte Giordano and her reluctance to spend any more time within its walls than she could possibly avoid, Felice recognized its importance – physical, economic and symbolic – to her sons’ patrimony and their prestige in Rome. Monte Giordano had suffered considerable damage during the Sack. The Orsini French connection was well known and the palace had been one of the first targets of Imperial attack, set ablaze on the first day. To leave the burned and blackened exterior unrestored would be to preserve a symbol of the Orsini family’s humiliation and defeat. However, this need to repair the damage also gave Felice the opportunity to dissociate herself further from her Orsini relatives. Monte Giordano was not one single integral palace, but a citadel-like settlement of several adjoining buildings situated around a courtyard, each belonging to different branches of the Orsini family. The Bracciano Orsini had always occupied the largest wing, but now Felice chose to ensure, through architectural devices, that from the outside her family appeared as removed as possible from the rest of the Orsini clan. After the completion of the renovation in the

1530

s, Felice spent much more time in Monte Giordano than she had in the previous decade. It was as if, having placed her own seal on its fabric, she was finally comfortable within its walls.