The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere (36 page)

Read The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere Online

Authors: Caroline P. Murphy

Tags: #Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #History, #Renaissance, #Catholicism, #16th Century, #Italy

The following day, business negotiations began with the invaders, transactions that suggest that Isabella’s offer of shelter might not have been entirely altruistic and that shelter did not come without a price. The first Imperial officers to arrive at the palace were Ferrante Gonzaga, along with his cousin, Alessandro Novolara Gonzaga, a captain of the Emperor’s army. They recognized the financial value of the assembled company, and they called the Emperor’s Spanish lieutenant, Alonso da Cordova. ‘He entered,’ wrote Como, ‘saying he was in need of a good drink, and he began to make calculations, not of how much the Marchesa and her goods were worth, but of all the others. He demanded no less than

100

,

000

ducats, declaring that they could easily afford such a small sum.’

6

But the assembled hostages were not Renaissance business men for nothing, and they haggled with Cordova about how much they could pay, beating him down, narrated Como, ‘to

40

,

000

ducats, and then with an

additional

12

,

000

, which in total made

52

,

000

ducats. This was paid in money and silver, and of the thousands that were missing, in bank credits. Of the first

40

,

000

, half went to Alessandro Novolara, the other half to the Spanish captain. Of the

12

,

000

,

2000

was given to four

Landsknechts

and the other

10

,

000

, some say, was secreted away by Don Ferrante. We do not know if this is true, but if it is, it would have been very dishonest.’ The hostages were, after all, Ferrante’s mother’s visitors, and it is hardly polite to extract

10

,

000

ducats from one’s overnight guests, no matter what the circumstances.

Not everybody could afford the same amount. Felice stood security for others for small and large sums. She contributed

150

ducats for the ransom of the Genoese Pietro di Francesco, and promised

2000

ducats on behalf of her nephew, Francesca de Cupis’s son, Christofano, who was of far lesser standing than herself. How much she paid for herself is unknown, although undoubtedly it would have been several thousand ducats. She gave up her jewels for ransom, including her most treasured possession, the diamond cross her father had given her after her marriage, for the equivalent of

570

ducats.

Felice’s long-standing relationship with Isabella d’Este allowed her the privilege of being among the first to go. The Marchesa of Mantua was anxious to leave Rome, although such an exit was not deemed prudent until

13

May owing to the continued carnage in the street. The Sack of Rome was by then over a week old.

Outside the fortified walls of Dodici Apostoli, the streets of Rome had become human abattoirs, depositories of rotting flesh. It is hard to imagine how sickened Felice felt. Rome was her city, on which her father had lavished loving care, a city of which she had become a symbol of its golden age, a city whose future was represented by her sons. What future could she see now among the dead bodies and the burnt-out houses, especially when she had no way of knowing whether her sons were dead or alive?

chapter 4

The party’s journey to the Roman walls was a relatively safe one as Isabella’s son Ferrante supplied them with an escort. Travel beyond the walls was another matter. Gian Maria della Porta, the

nuncio

for the court of Urbino, another member of their party, gave a graphic account of their journey:

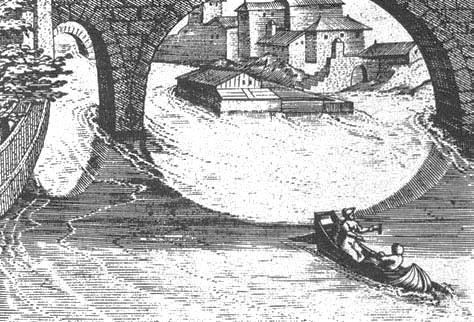

Finally we left Rome accompanied by Signor Ferrante Gonzaga, who took us all the way to the road to Ostia, from where we were to take a boat. But as we arrived there, the wind changed, and we were obliged to spend the night sheltering by the city walls, in greater danger than had we stayed in Rome. The following day we could go no further than the Magliana [the papal villa built by the river, from where they could sail to the coast]. Finally yesterday it pleased God to take us to Ostia, from where we are hoping to leave as soon as possible...

1

An hour before midnight, the group sailed from Ostia to the port of Civitavecchia, which they reached in the small hours of the morning. Boats were in great demand at the port, but this was an occasion on which Felice could be the one to give assistance. The Genoese sea captain Andrea Doria was in charge, and he gave Felice the deference due to the woman who had once been Madonna Felice of Savona. He helped Isabella get ships to take her and the considerable quantity of possessions she had acquired in Rome back to Mantua.

Felice had to wait for the arrival of Gian Domenico and her sons before she could do anything, and her relief was immeasurable when they finally appeared at the port. Now that they were all finally out of Rome, she could take in the extent of their plight and her own helplessness. Here she was, a woman in charge of vast estates in the Roman

campagna

, and it was too dangerous for her to go to any of them. All were prime targets for the Imperial troops. They were burning much of the surrounding countryside in order to deprive the Romans of food supplies. This action only compounded Rome’s pre-Sack food shortage, brought on by the huge numbers of pilgrims who had come to the city in

1525

for the Papal Jubilee.

Greater than Felice’s fear of Charles V’s army was her fear of Napoleone. The rage of the imperial troops would eventually burn out but Napoleone’s never would. In March

1527

Napoleone had been arrested for entering into anti-papal negotiations with the Spanish viceroy in Naples and had been imprisoned in the Castel Sant’ Angelo.

2

But Napoleone, along with other prisoners, had escaped from the Castel when the Sack began. All had taken a vigorous part in the killing and looting, unconcerned that it was fellow Romans they were attacking. Felice knew he would not hesitate to take advantage of Rome’s anarchic state to pursue her and her children if he could, to take them hostage or even kill them. She was also sure Napoleone would feel confident that he would be free from the threat of any papal reprisal. Pope Clement VII had reneged on the payment of most of a

400,00

ducat ransom to the Emperor. The Pope had then fled to Orvieto,

126

kilometres to the north of Rome. Orvieto was a nearly inaccessible hill town, easily defended, with the added benefit of a papal palace built during the late Middle Ages. Hidden away in the hills, Clement was in no position to offer the protection he had given Felice in recent years.

Felice knew her only option was to flee far from Rome, and she considered where she might find suitable accommodation, perhaps for a lengthy period. She might have gone to Mantua with Isabella d’Este, or to the island of Ischia, off the Neapolitan coast, where the noblewoman and poetess Vittoria Colonna was offering shelter to a number of Roman nobles and humanists. Instead, Felice turned to her blood relations, her cousins in Urbino, Francesco Maria della Rovere and his wife Eleonora Gonzaga. The della Rovere cousins were a logical choice. Felice was on good terms with them, and she had made numerous efforts on Francesco’s behalf over the past years. She was also aware that neither Francesco Maria nor Eleonora was currently resident at Urbino. Francesco Maria, however nominally, was still commanding the Holy League from a camp outside Viterbo, some fifty miles to the north of Rome. Eleonora divided her time between her parents’ home in Mantua and Venice. So Felice had good reason to believe that they had room to spare at their ducal palace. And like Orvieto, Urbino was high in the hills. Felice and her family would be far from the reach of Napoleone.

Felice and the de Cupis family split up once again. This time, Felice took her three children, and her mother, sister and brother stayed together for the journey to Venice. At Civitavecchia, Felice commanded a ship robust enough to undertake the long sea voyage from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic coast. The family sailed south. They rounded the heel of Italy, and then sailed north until they reached Pesaro, the largest port in the Duchy of Urbino. The devastated city of Felice’s birth was left far behind and she could finally feel she and her family were out of danger.

chapter 5

Even today, Romans often make the Marche, the province containing Urbino, a summer retreat. Its hilly peaks, which are not quite mountains, are still verdant when all else is parched, and the landscape is wilder and more densely wooded than the cultivated fields of the northern Lazio. For the Orsini

gubernatrix

and her children, this country was to be a similar kind of retreat, a haven.

By the beginning of June

1527

, Felice and her children had settled in Urbino. From his battle camp at Viterbo, Francesco Maria wrote to her to ease her lingering fears. He assured his cousin that she was not to worry. ‘I think of your children as my own,’ he wrote. ‘You are now in a safe place and the Abbot [Napoleone] will not be able to get to you.’

1

In return, Felice wrote a series of grateful letters to her della Rovere cousins. Each expresses her thanks more fervently than the last, and are a far cry from the businesslike missives she wrote in the first person plural to her servants. The first letter announced that she and her children could never fully express the obligation they felt to their highnesses. The second, to the Duchess, told of her gratitude for the kindness of all at court, which was such that, Felice claimed, ‘a hundred tongues could never tell of it’. The third, again to the Duchess, was even more fulsome:

I would like to be able to show my mind’s conception of the expression of my obligation, and that of my children to his excellency the Duke, and to your ladyship. So much humane action never ceases to invoke in me a continual sense of obligation: what gentility and rare virtue you have shown towards me, your servant, and what memories I retain of it. And what merits even more praise is that I know that your demonstrations to me are not those of a lady and benefactress, but of a sister. Only God knows how you can be rewarded for your goodness. My tributes to you could never be sufficient were I to live for a thousand years.

2

Three letters expressing more or less the same sentiments, however heartfelt, might seem more than sufficient. However, Felice was aware that more and more refugee Roman nobles were drifting towards the expansive Urbino court, seeking assistance. She was apprehensive that the della Rovere dukes might feel obliged to help these displaced nobles too. After all, Francesco Maria’s military tactics had contributed to their predicament. Felice had no desire to suffer the indignities of overcrowding; the period she had spent at Dodici Apostoli with two thousand fellow Romans had undoubtedly been enough. So she constructed this last letter to Eleonora with the aim of reminding her cousin that her obligation to Felice was one bound by the special ties of blood and not simply charity. Felice knew she was due, and should receive, preference.

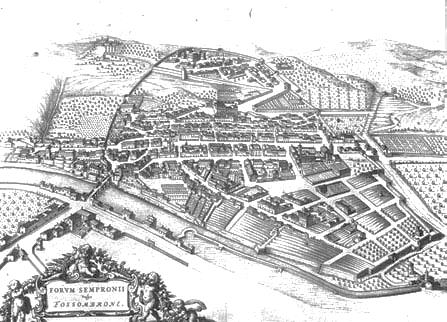

Felice’s solicitations proved effective in helping her obtain what she wanted. So rather than reside in a palace potentially filled with any number of Roman neighbours, she contrived a relocation to an Urbino fiefdom in which she could create an establishment for herself. The della Rovere offered her a palace of her own in the small hillside town of Fossombrone.

Fossombrone is about thirty kilometres to the north-east of Urbino, in the foothills of the Alpe de la Luna. It was one of the ancient settlements in the province of the Marche, deriving its name from its original Latin title, ‘Forum Semprone’. The town, now rather sad and dusty, was acquired in

1445

by Francesco Maria’s grandfather, the great duke and

condottiere

Federigo da Montefeltro, from the Malatesta, the famed tyrants of Rimini. Federigo had built a small palace at the top of the town known as the Corte Alta, the ‘High Court’. In the second part of the fifteenth century, Fossombrone served as an attractive retreat for the Urbino court. It was reasonably close to Urbino itself, yet isolated enough to be quite private. It was renowned for its pure water and good air, so might be said to be the ideal environment for a woman and her family attempting to recover from the traumatic ordeal of the Sack of Rome.