The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere (35 page)

Read The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere Online

Authors: Caroline P. Murphy

Tags: #Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #History, #Renaissance, #Catholicism, #16th Century, #Italy

Charles, angered by Clement’s treachery, sent thirty thousand soldiers into Italy late in

1526

. His troops, led by the Duc de Bourbon, consisted primarily of Spanish and German soldiers, the famous

Landsknechts

, augmented by some Italians. The Bourbon Duke envisaged a few skirmishes in northern Italy as enough to make Clement change his mind and switch his loyalty back to Charles. The Emperor would pay his troops and they could return home. The Duc de Bourbon’s victories were indeed substantial. He even felled the last of the great

condottieri

, the Medici Giovanni delle Bande Nere, whose mercenary soldiers, the Black Bands, were the best in Italy. Nevertheless, despite military losses, Clement did not capitulate. Nor did Charles V pay his troops and the soldiers, rendered ferocious by starvation, continued the march south.

Two of Felice’s relatives also played a part in bringing the Sack upon Rome. Her cousin Francesco Maria della Rovere, the Duke of Urbino, was Captain General of the Venetian troops, the most substantial of the armies assembled to block the Imperial invasion. Clement gave him command of the troops of the entire papal Holy League, who were employed to keep back the Emperor’s army. But Francesco Maria did not behave as might have been expected of a general fighting on his home territory. Rather than pressing his advantage and acting aggressively to rout the invaders, he avoided meeting the Imperial troops in armed combat. When he did advance, he almost immediately ordered the retreat of his own men. Guicciardini voiced his scorn for Clement’s appointment of Francesco Maria as his general: ‘What did Clement think would happen?’ he asked. ‘His immediate predecessor [Leo] had taken the Duke’s estate; when he [Francesco Maria] was finally able to show his contempt and hatred for the Medici family, was it likely that he would conceal it, or give up before he saw that family ruined and destroyed?’

3

Greatly assisted by the Duke of Urbino’s strategy of revenge on the Medici, the Emperor’s soldiers advanced closer and closer to Rome. At the beginning of May, they reached the Aurelian walls, on the upper slopes of the Janiculum Hill, above St Peter’s.

Francesco Maria della Rovere, one of Felice’s favourite relatives, facilitated the Imperial troops’ arrival at the gates of Rome. Renzo da Ceri, one of her more troublesome Orsini cousins, allowed them into the city. His actions, though, were the result of incompetence rather than malice. ‘The Pope had no time to search for troops in the areas where good and courageous ones were to be found,’ explained Guicciardini. ‘Consequently he was forced in furious haste to arm about three thousand artisans, servants and other simple people.’ This army of scullions would scarcely have been sufficient to hold back the Imperial forces, but ‘more often than any other officer, Signor Renzo declared his opinion that the enemy could not last two days outside the walls because of their lack of food’.

4

The enemy, however, had no intention of remaining outside the walls. The Aurelian walls were weak. They had undergone little major reinforcement since the days of ancient Rome, and had received only perfunctory attention in preparation for this siege. This time, it was another of Felice’s associates who was at fault, as this task had been placed in the hands of Giuliano Leno. Bourbon, prior to the assault, made a speech designed to rouse his soldiers’ mettle. Not only did he remind them of ‘Rome’s inestimable wealth of gold and silver’, which would be theirs for the taking; he also told them, ‘When I look into your faces I plainly see that it would be much more to your liking if waiting for you in Rome were one of those emperors who spilled the blood of your innocent ancestors...You cannot avenge the injuries of the past; you must take whatever revenge you can.’

5

Spurred on by the idea of revenge on the ancient Roman Empire, the Imperial assault began. Bourbon, in an effort to encourage his men further, made a foolish decision. He took the front line and so was one of the first to be killed, shot by an arrow from a papal arquebusier. His death meant there was no leader to control the fury and rage of his soldiers as they stormed the city. The pathetic Roman guard was powerless to stop them and simply fled. Having penetrated the city walls near the Vatican, the Imperial troops made their way through Trastevere, over the Ponte Sisto, the ancient bridge restored by Felice’s great-uncle Sixtus, and into the heart of the Roman

abitato

. Many of the Spanish soldiers had participated in the taking of the New World, and in the sack of the Aztec capital of Tenochitlán. They now applied those devastating and ruthless methods of conquest to the Eternal City. They imprisoned the inhabitants of the homes they captured and no type of torture was too extreme if it meant their prisoners would reveal where they had hidden their treasure. Afterwards, the Iberians torched the properties. By the evening of

6

May much of Rome was ablaze.

Noble families had gathered together for protection in Rome’s larger palaces, believing in safety in numbers, but such safety was by no means assured. Felice’s wealthy neighbour, Domenico Massimo, was killed by the Imperial troops at his palace on the Via Papalis, the ceremonial route Julius II had taken pains to improve and maintain. So were Domenico’s wife and children and along with them many other noblemen and women who had sought shelter at the home of Rome’s richest man. ‘Just imagine with a heavy heart’, wrote Scipione Morosino to his brother Alessandro, the chamberlain of the Duke of Urbino, ‘those poor Roman noblewomen witnessing their husbands, brothers and children killed in front of their very eyes – and then, even worse, that they themselves are murdered.’

6

Where was Felice della Rovere as Rome was destroyed? She could have avoided the Sack entirely. In April, she had received an invitation from her daughter Julia’s sister-in-law, the Duchess of Nerito, to tour the southern province of Calabria. But Felice had not taken up this offer as she was reluctant to leave Orsini lands, fearful of disturbances breaking out in her absence. Ironically, her worst fears were to be realized without a trip to the south. She and her children, Francesco, Girolamo and Clarice, were all trapped in Rome as hell descended around them.

Felice’s name had always encouraged word play. Her correspondents always wished her

felicità

, or called her a

domina felix

. Yet never had her name been as apt as it was on the day of the Sack. Her current distaste for staying at the Orsini palace of Monte Giordano probably saved her life and those of her children. Monte Giordano was one of the first Roman palaces attacked by the Imperial soldiers, the Orsini family being traditional supporters of the French, the Emperor’s great enemy. By the end of the first day of the Sack, the invading troops had stormed the great gate of Monte Giordano, and set the family compound on fire. A poet, Eustachio Celebrino, declared in verse that, ‘Monte Giordano was set ablaze and burned to the ground.’

1

Celebrino did use some poetic licence as damage to the palace was not so severe but there is little doubt that had Felice and the children been inside the palace, they would have met the same fate as their Massimo neighbours.

As the Sack began, Felice and her children were all together at the Palazzo de Cupis with Lucrezia, Gian Domenico and Francesca. As grand as the de Cupis palace was – Gian Domenico had continued to enhance the house his father had built – it had not been designed as a stronghold and lacked fortifications. Felice and her family knew it would not withstand any kind of a siege. They had to act quickly if they were to save themselves from the invading troops as the battle cries and the shouts of terror from the victims grew closer and closer. Although many of Clement VII’s cardinals had scrambled to be by his side, and were now with him at the fortress of Castel Sant’ Angelo on the Tiber river, Gian Domenico knew that his first loyalty was to his family. Together, they decided that they would stand a better chance of survival if they did not try to escape as one group. They could move faster and would be less conspicuous if they grouped themselves by gender. Gian Domenico and Felice’s sons, Francesco and Girolamo, went as one group; Felice, her mother, sister and daughter as another.

Gian Domenico did not initially take his nephews very far. They simply crossed the street to find refuge at the palace of his neighbour, the Flemish Cardinal Henkwort, adjacent to the German church of Santa Maria dell’ Anima. Gian Domenico’s reasoning for seeking refuge from Henkwort was entirely logical. Henkwort was the most distinguished northern prelate in Rome and so presumed to be immune from attack by his countrymen. Nor was Gian Domenico alone in his thinking; many others had crowded into Henkwort’s home.

Unfortunately, neither the

Landsknechts

nor the Spanish soldiers had any respect for geographical ties when there were riches to be had. For them everyone in Rome was Roman and ‘the Spanish and the Germans, be they priests, or officials or courtiers, were all sacked and taken prisoner, and sometimes treated more cruelly than the others’.

2

The soldiers went systematically to the other cardinals’ palaces, to those of Cesarino and della Valle, who were also Imperial sympathizers. Not only did they strip their homes of all their riches; they demanded ransoms from those sheltering inside. Henkwort was no exception. ‘All the cardinals’ homes were sacked,’ the Cardinal of Como explained to his secretary, ‘even those who were Imperialists. The house of della Valle was robbed of more than two hundred thousand ducats, as was that of Cesarino, those of Siena and Henkwort more than a hundred and fifty thousand, and they made hostages of those inside with ransoms of thousands upon thousands of ducats.’ The hostages paid the ransoms, or

composizione

, in whatever wealth they had on them, supplemented by promissory notes. Yet payment of ransom was no guarantee of personal safety. The soldiers killed many of their victims after extracting their money.

When the Imperial soldiers came to Cardinal Henkwort’s palace, Gian Domenico paid

4000

ducats as security for himself, Francesco and Girolamo. But he quickly realized that such a payment would not ensure their safety. Gian Domenico had not spent the last ten years of his life working to protect his sister’s and her children’s interests to let them, or himself for that matter, die on an Imperial sword. He must also have been very afraid of what would happen were the enemy to learn that Francesco and Girolamo were heirs to the Orsini lordship. So he decided that he and the two teenage boys would escape from Rome. ‘Letting themselves down by a rope, they exited Henkwort’s palace and the city of Rome,’ wrote Como. ‘They went many miles on foot, and encountered many dangers.’

3

Their journey was a long and circuitous one, for the countryside was swarming with Imperial soldiers. But a man with two teenage boys could travel in disguise relatively easily. They acquired a mule, and passed as

mulatieri

, the ubiquitous mule-drivers. Gian Domenico rode the mule and the two boys went on foot. They made first for lake Nepi, which had been designated a safe stop, free from Imperial soldiers. Their ultimate goal was the sea, and boats to freedom, and so the port of Civitavecchia north of Rome was their planned destination. A week after setting out, they finally reached the port, where ‘they are now’, reported the Cardinal of Como, ‘safe among us’. Of all the great palaces in Rome, ‘only the house of the Marchesa of Mantova, Isabella d’Este, who was staying in the great palace of the Santi Dodici Apostoli, built by Papa Julio, remained unharmed’.

4

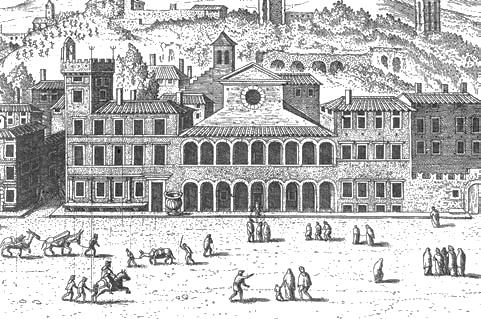

It was Felice’s great fortune that Dodici Apostoli was the place where she chose to take her mother, daughter and sister. Isabella d’Este had come to Rome to secure a cardinal’s hat for her younger son, Scipione, and she had rented the Dodici Apostoli palace from the Colonna family for the duration of her visit. She was perhaps less alarmed than others by the threat of the invading troops as her nephew by marriage was the ill-fated Duc de Bourbon and serving under him as chief lieutenant was her own son, Ferrante. Isabella was confident of a considerable degree of protection. Moreover, Dodici Apostoli was, as the Cardinal of Como noted, ‘extremely well fortified, with bastions on every doorway’, and difficult to penetrate. Isabella sent out word that she would offer shelter to any noble who could make it to the palace. By the end of the day of

6

May, ‘more than a thousand women, and perhaps a thousand men’ were inside Dodici Apostoli.

The initial journey for Felice and the other women was as harrowing as it had been for Gian Domenico and the boys, if not more so. They were much more vulnerable than the men, as their group comprised two women in their forties, one in her sixties and a fourteen-year-old girl, and they could not move as quickly. They had to make their way through the narrow streets from Piazza Navona up behind the Via Flaminia (presentday Via del Corso), the location of Dodici Apostoli. Throughout Rome, women like them were being raped and murdered. But this was not the first time in Felice’s life that she had had to resolve that she would not be taken by Spaniards, and they reached the palace her own father had built almost half a century earlier in safety. They were shrewd enough to dress plainly, realizing that ornate costume would draw attention and betray their noble status. One commentator described them arriving at Dodici Apostoli wearing only ‘simple gowns’.

5

However, beneath these simple gowns they had concealed Felice’s fortune in gems. Her decision, made years earlier, to collect only what could be easily transported, had proved wise. The assembly of Roman nobles and foreign emissaries passed the night at the palace, listening to the destruction of a city. Many beat on the great door of Dodici Apostoli, begging for entrance. Others attempted to break it down, but the portal did not open for them.