The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere (39 page)

Read The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere Online

Authors: Caroline P. Murphy

Tags: #Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #History, #Renaissance, #Catholicism, #16th Century, #Italy

Fittingly, the architect Felice probably employed in this enterprise was the one she had commissioned to design Bracciano’s

fonte

, Baldessare Peruzzi. Poor Peruzzi had suffered badly at the hands of the Imperial troops. Vasari wrote:

Our poor Baldessare was taken prisoner by the Spaniards, and not only lost all his possessions, but was also much maltreated, because he was grave, noble and gracious in demeanour, and they believed him to be some prelate in disguise, or some other man able to pay a fat ransom. Finally, however, those impious barbarians having found that he was a painter, one of them, who had borne a great affection for Bourbon, caused him to make a portrait of that most rascally captain, the enemy of God and man, either letting Baldessare see him as he lay dead [Bourbon was laid out in the Sistine Chapel] or giving him his likeness in some other way, with drawings, or words.

1

Peruzzi was one of the architects who contributed to the renewal of Rome. He designed a beautiful scheme for the renovation of the palace belonging to the wealthy Massimo family, who had lost not only their home but many family members in the Sack. Prior to the Sack, in

1525

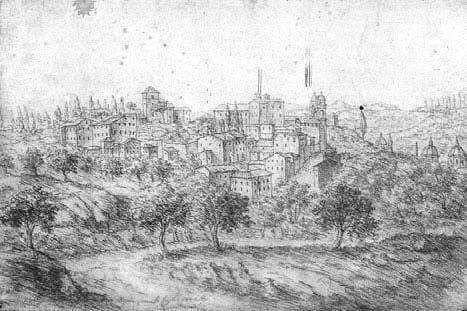

, he had converted the upper storeys of the ancient Teatro Marcello into a palace for the Savelli family, who also owned the Colosseum and rented its upper storeys to hermits and mystics. At the Teatro Marcello, Peruzzi designed a façade for the Savelli, which, with its strategically designed details, would provide optimum legibility when viewed along the narrow street on which Teatro Marcello stood, thereby augmenting the Savelli’s visual presence in the city. He accomplished this effect through a simple but ingenious optical device: inflating the scale and relief of the façade’s window details. A similar strategy is employed on the upper storey of the Bracciano wing at Monte Giordano, which is also situated on a narrow street. Peruzzi’s architectural design gave visual definition to the part of Monte Giordano where Felice and her family resided. It provided a dramatic break, which is still visible today, between the Bracciano palace and the other Orsini buildings within the complex. When the latter were repaired, it was in the late-medieval style of their original design. This emphatic visual separation, at least as far as Felice della Rovere was concerned, served not only aesthetic purposes but social and political ones as well.

For Felice, renovating the palace at Monte Giordano was important for family pride and self-esteem. Renovating another Orsini palace on the market place of Campo dei Fiori was critical for economic reasons. Embedded within the ancient fabric of Pompey’s Theatre, the Campo dei Fiori palace had been the original Roman residence of the Orsini. However, for as long as Felice della Rovere had been attached to the family, the Orsini had rented Campo dei Fiori to cardinals as yet insufficiently wealthy to afford a palace of their own in Rome. The let provided a twofold advantage: income as well as the good will of a cardinal who could become another ally at the papal court.

Campo dei Fiori, which was both market square and residential area for merchants and cardinals, had been an easy target for the Imperial troops who had destroyed some of the palaces flanking the piazza, including the one belonging to Cardinal del Monte, the future Pope Julius III. The damage to the Orsini palace was not so complete. Its ancient foundations had, after all, withstood more than one assault by foreign invaders, but the palace still needed repair. Felice della Rovere did not commission an illustrious architect to undertake its renovation. She probably did not feel the Campo dei Fiori palace, which was a glorified boarding house, needed a new and decorative façade in the way Monte Giordano did. Instead, she hired Ambrosio da Lodi, a

muratore

, a more humble builder, to repair the damage to the palace walls. Ambrosio worked full time for Felice for two years, receiving monthly payments of one or two

scudi

‘for the work on making the walls of the palace at Campo dei Fiori’.

2

Felice also employed Ambrosio at Monte Giordano, making door and window frames.

Despite the damage to the Campo dei Fiori palace, it was still a viable let. Property was at a premium in Rome as so much housing had been rendered uninhabitable during the Sack. Felice had an eager and potentially useful new lodger in the form of the Archbishop of Matera, Cardinal Andrea Matteo Palmieri, a long-standing acquaintance. There was a record of him having loaned her

190

ducats in

1525

to pay for soldiers serving as bodyguards to Girolamo to protect him from Napoleone. Palmieri, from Sicily, which was under Spanish governance, had been one of seven new cardinals appointed by Clement VII in November

1527

as a good-will gesture to Charles V. With no palace of his own in Rome, the new Cardinal was in need of substantial accommodation. Renting Campo dei Fiori to him gave Felice access to the Imperial camp should she need it. In accordance with the mandates from Clement that Napoleone be informed of all activity regarding Orsini property, Felice duly wrote to him. His reply was predictably contrary: ‘I received your letter in which you inform me that I must be content that our house at Campo dei Fiori is to be had by Cardinal Palmieri. I reply to you that I cannot be content as I promised it to another and I do not wish to be less than my word, and God knows how much I have sacrificed in other matters for love of you and my brothers. Nothing else occurs to me. I recommend myself to you.’

3

Felice appears to have gone ahead, despite Napoleone’s protests, with the let to Palmieri. Although she was prepared to rent Campo dei Fiori to a Sicilian who had helped her in the past, Felice must have had ambivalent feelings towards the Spanish themselves. They had wrought untold damage on her property and possessions at Trinità dei Monti. The convent of Trinità dei Monti had some association with the French crown – the friars who resided there were Franciscan Minims. Their founder, Francesco di Paola, had gone to France in the late fifteenth century as a spy for Sixtus IV. He had stayed at the French court as confessor to the French queens and Louisa of Savoy named her son, the future Francis I, after him. Some French money had gone towards the building of the Minims’ church in Rome. This French tie had made Trinità dei Monti a prime target for Spanish rage. But it was not the French who were to suffer but the Italian friars, not to mention Felice herself. When the realities of the Sack hit home, Felice had arranged to have the precious objects and valuable papers she kept in her palace adjacent to Trinità transferred to the church. As many had done, she believed that Rome’s holy places would be safe from attack. She was to be proved very wrong.

chapter 9

Felice was in Fossombrone when she learned of the horrors unleashed at Trinità dei Monti. In July

1528

, Benedetto di San Miniato, now her chief

maestro di casa

in Rome, sent her a report of the state of the convent he had received from a Genoese friar who had gone to stay at Trinità just before the Sack occurred: ‘This friar tells me he is a loyal servant to your ladyship, and being at the church he was able to tell me all that happened to the young friars and their father. Of the friars only thirty-three remain alive; the others are dead, either martyred, or from fever and plague.’ There was certain irony here, Trinità dei Monti, with its secluded hilltop location, was usually safe from plague, and had served as a refuge during previous outbreaks of the disease. Benedetto went on to tell her, ‘The convent received much damage. The Spanish invaded the sacristy and sacked the convent very badly, burning, setting the woodwork, doors and windows alight. And the Genoese friar tells me that the Spanish took away the papers and other things belonging to your ladyship.’

1

The Spanish also went on to ravage Felice’s own adjacent property, the garden, the vineyard and the palace itself. On her return to Rome, Felice had set about a comprehensive renewal of the Trinità dei Monti property. In September

1531

, ‘Maestro Menico Falegname [carpenter] da Formello was given one

scudo

to buy hinges and other things to make beautiful doors

at the Trinità.’ ‘Menico da Formello was given five and half

scudi

for hinges, a lock and key for the Trinità.’

2

For the outdoors, she hired an entirely new team of gardeners, who erected a new vineyard and re-created the pleasure garden, which had been the subject of admiration by Felice’s guests in earlier years.

The other treasured possession of Felice’s that the Spanish stole and then desecrated was her diamond crucifix, the one given to her by her father and which she had given up as ransom that night at Dodici Apostoli. She had written from Urbino to the Bishop of Mugnano, who had been so skilled at locating the jewel she had given as a baptismal gift to the Monterotondo Orsini, hoping he could help her find the crucifix. He professed to have heard nothing about its possible whereabouts. Much later, in November

1532

, she would receive a letter from an Italian, Giovanni Poggio, in Madrid. Poggio had discovered its location, and he was prepared to broker its return to her. He wrote:

I found myself in these parts the other day with the Viceroy of Navarre, the brother of the late Alonso da Cordoba [the Spaniard responsible for assessing the ransom of those nobles at Dodici Apostoli] whom your ladyship will remember for the time he was in Rome when Rome was sacked. He came to discuss business with me, and told me that Don Alonso his brother had told him at the time of his death that he held a diamond crucifix belonging to you valued at

570

ducats, and that the said cross has lost two diamonds. If you wish to have the crucifix restored to you, you can pay him the

570

ducats, less the value of the two diamonds. The price, as your ladyship knows, is estimated on the value of other similar items...All I desire to know is whether your ladyship would like me to proceed in the recuperation of the cross.

3

Felice’s cross had had a life story of its own. It had been a diplomatic gift, offered by the city of Venice to Pope Julius. In presenting it to his daughter, the Pope had used it as a token of reconciliation, where it became the prize piece in Felice’s jewellery collection. She in turn had had to use it as ransom, handing it over to Cordoba. The Spaniard had then gouged out two of the cross’s individual gems, using them for wages or bribes, desecrating the cross for purely practical reasons.

Badly as she wanted to see her cross removed from the hands of the unconscionable Spanish, and returned to her, its rightful owner, by late

1532

Felice was suffering from severe financial constraints. Heavy responsibilities, both past and present, meant she did not have the ready cash to retrieve this prized possession.

chapter 10

If Felice was unable to secure the return of a memento of her father, she was more successful in helping to ensure the completion of a memorial to him. The Sack had made this urgent, for the church of St Peter and the Vatican Palace had been particular targets for Imperial destruction. Storming the Vatican Palace, the German soldiers used their daggers to score into the famous frescos painted by Raphael in Julius’s apartments the name of Charles V and mocking anti-papal sentiments such as ‘You should not laugh at what I write. The

Landsknechts

have run the Pope out of town’; or, quite simply, ‘Babylon’. These graphic reminders of their desecration are still visible today. In the meantime, the Spanish plundered Julius’s tomb in the choir of the Petrine church. The prelate Pietro Corsi lamented, ‘Entry was made even into graves and rich tombs...the diamond ring and emeralds were wrenched from fingers. Who could take such liberties with you, Julius, greatest of popes and best father of fathers?...[From you] the unpacified Iberian has not feared to despoil the right hand of its signet ring after you were buried.’

1

Other reports claimed that after robbing the pontiff’s tomb, the Spanish soldiers played ball with his skull. Of all the insults the Imperial troops had heaped on the papacy, the plundering of Julius’s tomb and the desecration of the body of this father of new Rome were seen as among the most heinous.