The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere (43 page)

Read The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere Online

Authors: Caroline P. Murphy

Tags: #Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #History, #Renaissance, #Catholicism, #16th Century, #Italy

Napoleone continued to be a tenacious adversary. On

4

November, impatient that his enemy had not yet met his demands, and seeing that the number of troops attempting to storm Vicovaro had not diminished, he attempted to escape, taking Girolamo with him. However, soldiers impeded his way and Napoleone retreated back into the castle. A few days later he contrived to escape by himself, but not without taking, as one of Felice’s servants informed her, ‘all the silver from the church and crosses and altar cloths, and everything. All he has left is one cloth for the saying of the Mass.’

12

Napoleone’s departure precipitated the capitulation of the castle, and Girolamo was finally released. When the soldiers stormed Vicovaro, only three of Napoleone’s men were left guarding Girolamo. At the sight of his rescuers Girolamo declared that he thought he would never be released. Napoleone was gone for the moment, but all knew he would return before too long. For the time being, at least, the business was concluded, as a summary was sent to Venice: ‘Signor Alvise Gonzaga has retaken Vicovaro, Signor Napoleone had fled, Signor Alvise was thus able to take the land, and Signor Girolamo brother of the said Napoleone who was imprisoned is now liberated.’

13

The war of Vicovaro had been costly, not only to Felice personally, but also to the papacy. Not only had Clement spent a great deal of money, he had also lost a papal commander far more reliable than Renzo da Ceri or Francesco Maria della Rovere. He made it clear to Felice that in order to avoid a repetition, the situation between the Orsini brothers must be resolved. France put pressure on Clement too. In

1533

, ‘through the intercession of King Francis I’, Clement passed an act absolving Napoleone for his actions, along with his band of sixty-six men.

14

A division of Orsini property had also to take place, known simply as

la divisione

. However, Napoleone was not to be found, and was thought to have escaped to France. Girolamo too disappeared for much of that year, so little progress was made with the partitioning of the estate.

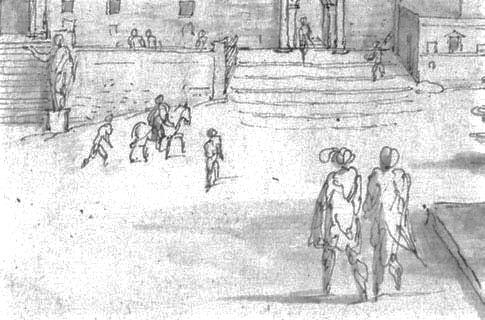

C. Boel, after Antonio Tempesta ‘Bourbon sends Troops to Attack’

chapter 14

Appearance was still a critical matter for Felice. It did not matter that the previous year had seen the most public demonstration yet of the rift between the brothers, or that Napoleone might get his way and receive a significant portion of the estate. She had to ensure that her family appeared stronger than ever. The structural restorations to the fabric of Monte Giordano were complete, and she had acquired sumptuous new furniture carved from oak and walnut. Felice began to entertain at the palace in a way she had not done before. For the Shrove Tuesday carnival festivities, she hosted what was to be described as one of the grandest events ever at Monte Giordano. It was traditional for widowed noblewomen to host a carnival celebration to which only women were invited. Felice’s guests included the mother and illegitimate daughters of Cardinal Franciotto Orsini, with whom Felice had come to be on better terms since he had attempted to help her in the negotiations with Napoleone at Vicovaro. Also invited were her cousin Maria della Rovere and her daughter, and the wife of Gregorio Casale, a Vatican financier from Bologna. The guest of honour was Portia Colonna, a widowed matriarch like Felice herself, thus her counterpart in the other great Roman family. Portia was accommodated in one of the most magnificent new rooms, described as containing two beds and sumptuous wall hangings. Francesco Orsini’s servant wrote to inform him that ‘the party was one of the greatest ever, and a beautiful comedy was performed by servants of the Reverend Trani’.

1

For Christmas

1533

, the whole of Felice’s family gathered at Monte Giordano, the first time they had been together since the Jubilee of

1525

. Julia came with her husband, the Prince of Bisignano, and their two little girls, as did Clarice, accompanied by the Prince of Stigliano. Francesco and Girolamo were both present and the festivities extended into January. But the relative peace of

1533

proved to be a lull before the storm. As the party ended, word reached the family that Napoleone was riding to Rome, and everything changed.

If Girolamo Orsini had survived the siege of Vicovaro without sustaining much physical harm, the same could not necessarily be said of his mental state. Being taken prisoner and held captive by his half-brother was a deeply humiliating experience for a young man who prided himself on his warrior-like abilities, even if they had never been put to the test. The ways Napoleone baited Girolamo inside Vicovaro can only be imagined. Certainly he would have hurled insults at him, at his brother and especially at his mother, taunting him, declaring that his family must care little for him if they were not prepared to give up land to secure his release. Possibly Girolamo had come to believe this himself, which would account for his absences from his family during

1533

. Girolamo might have sworn loyalty to the Pope, but had undoubtedly sworn a personal oath that he would have his revenge on Napoleone.

Napoleone’s motivation for coming to Monte Giordano is unclear but appeared to centre around Clarice, and his desire to see her. Supporters of Napoleone claimed all he wished to do was to ‘kiss the hand of his sister [Clarice]’ prior to her departure south.

2

Such a desire on Napoleone’s part was met with trepidation by Felice and her family. It was unlikely that all Napoleone wished to do was to give a formal greeting to Clarice. Napoleone had always recognized her particular value. He had once before tried to force Felice’s hand by insisting that he be the one to determine her younger daughter’s future. Clarice, for her part, knew how dangerous he was. In his madness had he hatched some new plan to kidnap her and have her violated so that she would no longer be fit to be the Princess of Stigliano? Clarice, the Prince of Stigliano, and the Bisignano left as soon as they could. As the Prince of Bisignano would later report, ‘On our departure from Rome we were accompanied part of the way by the Signora Felice, her mother, the Abbot of Farfa [Francesco], and Signor Girolamo. Her mother and the Abbot turned back, and Signor Girolamo stayed to accompany us for some of the way.’ Napoleone caught up with them. Girolamo, enraged, turned to his hated half-brother, drew his sword and killed him. ‘Some’, remarked Bisignano, with perhaps a hint of understatement, ‘are of the opinion that the reason for this act is due to the enmity he has from the time that Napoleone captured him.’

3

Bisignano’s account of Girolamo’s killing of Napoleone is actually the most detailed in existence. To flesh out the scene any further requires a certain degree of imagination. Girolamo’s act of violence was an impetuous one, undoubtedly triggered by his memory of those terrible months as a hostage at Vicovaro. He now found himself facing, for the first time since then, the brother who had never been a brother to him. Girolamo now had the opportunity to take his revenge for his imprisonment, to protect his younger sister, to restore his honour and most importantly, to restore his honour in front of his brothers-in-law, southern princes both, for whom honour was the stuff of life. Few sword thrusts can have been delivered with as much hatred and satisfaction as Girolamo’s that day. And few can have been met with as much surprise. It was Napoleone who was the merciless professional soldier with the reputation for cunning, the one driven by an ever blazing rage. Girolamo was over a decade his junior, a mere boy who had never fought in a war, who had spent his life protected by his mother. Yet it was the boy who killed the man. The scene is of the type that would later appeal to nineteenth-century painters eager to capture the drama and gore of the Italian past. The first work the Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt publicly presented was a scene from fourteenth-century Rome, where the Roman hero Cola di Rienzo mourns his brother, killed in a skirmish between the Orsini and Colonna families. The painter vividly captures a road in the Roman

campagna

, the city visible in the distance. The attackers are now riding away, leaving a man to lament over the body of his dead brother. But while Napoleone had followers who mourned his loss, there was no mourning from his brothers, only rejoicing, and a profound sense of satisfaction at honour regained.

Girolamo’s action shocked the Italian nobility. Fratricide was not uncommon, but it was more normal practice to hire an assassin or a poisoner to do the deed. That Girolamo killed Napoleone with his own hands reflects his deeply entrenched desire to redeem his own honour. That, at least, was something his peers could understand, and was probably what eventually saved him. Although initially Girolamo was condemned to death by the city of Rome, in May of

1534

his death sentence was commuted to a brief term of imprisonment and the payment of a large fine described as

il debbito di sangre

, the debt of blood. The prison sentence was purely theoretical. After the murder, Girolamo had continued to ride on with his brothers-inlaw and was hiding at Cassano, the Prince of Bisignano’s estates deep in the south of Italy.

There is a surprising lack of documentation relating to the murder in the Orsini family’s archive. No letter survives referring directly to what had occurred. Clarice wrote to her mother on

22

March

1534

, telling her how sorry she was ‘to be absent from your ladyship’s side at this time’.

1

From April

1534

there is a letter to Felice from Girolamo written in his near illegible scrawl, in which little more than the word ‘disgratia’ can be deciphered.

2

There is another from this period to Girolamo from Portia Colonna, Felice’s guest at Monte Giordano the previous year for the carnival celebrations, in which she assures Girolamo, over and over again, of her love for him ‘as a sister’.

3

Yet it is as if every other reference to this event has been systematically removed from Orsini records, thus concealing an event that would stain the family’s reputation indelibly.

There is, however, a great deal of surviving documentation relating to the business end of the matter, the payment of the ‘debt of blood’. From Clement VII’s perspective, Girolamo’s removal of Napoleone was by no means to the Pope’s disadvantage. Napoleone, who had plotted to assassinate Clement and had assisted in a revolt in Tuscany against the Medici, had long been a thorn in the Pope’s side. Although Clement had often been exasperated by the behaviour of both Girolamo and Francesco Orsini, he had followed in his cousin Leo’s footsteps and always shown favour to their mother, but Napoleone’s assassination was not without potential political consequences and Clement could not now put his personal relationship with Felice above all else. Francis I of France had always been sympathetic to Napoleone and his claims, and Clement’s niece, Catherine de’ Medici, had been married the previous year to Francis’s son, Henry. Clement had no desire to provoke any kind of international incident by appearing to ignore Girolamo’s action, allowing it to go unpunished. In fact, what Girolamo had done presented Clement with a desperately needed opportunity to swell the papal coffers which were still drastically depleted following the Sack. The Pope confiscated Vicovaro and Bracciano.

The removal of Vicovaro was bad enough, but Bracciano was the hub, the nerve centre, of the Orsini economy. Without the Bracciano estate, the Orsini of Bracciano could no longer function. The removal of their patrinomic lands rendered them nameless and homeless. It was thus Felice della Rovere’s task to ensure that this option was not put into effect. To that end,

1534

was to see her perform the greatest acts of diplomacy and financial strategy of her entire life. She knew that if she were to succeed the greatest impediment to her son’s smooth succession as Bracciano lord had been removed. She could never have urged Girolamo to kill Napoleone; the consequences were too great. But now that Napoleone was out of the picture, the prospect of a trouble-free horizon spurred her on to retrieve her sons’ estate.