The Silk Road: A New History (39 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

With the weakening of the Kushan Empire in the second or third centuries

CE

, Indian migrants who crossed the Pamirs introduced Buddhist teachings to Khotan as they did at Niya. A prominent Chinese translator traveled from Luoyang to Khotan in 260 in search of the original version of an important Sanskrit text. After working for twenty-two years, he sent the written Sanskrit sutra to Luoyang but chose to remain in Khotan, where he died.

9

This account, preserved in an early sixth-century Chinese catalog of Buddhist texts, is the first written mention of Buddhism in Khotan.

DECORATIVE SKIRT BAND FROM SHANPULA

This skirt band shows a stag, its head weighed down by exaggerated antlers that fill the entire vertical frame. Colored pink, red, and blue, his four legs and tail stand out from the navy background. A creature—perhaps a bird with its head facing upward—rides on its back. Deer with giant antlers often occur in the art of neighboring Central Asian nomadic peoples. © Abegg-Stiftung, CH-3132 Riggisberg, 2001. Photo: Christoph von Viràg.

Khotan’s most imposing Buddhist ruin, Rawak, dates to this period as well. The site lies 39 miles (63 km) north of Khotan in the desert, east of the Yurungkash River. Visitors today take a car or bus to a location a few miles from the site, and then either walk (if it is not too warm) or ride a camel. The desert is blistering hot, and extraordinarily fine sand gets into everything, yet it teems with life: small plants, lizards, and rabbits thrive under foot, while hawks and larks fly overhead. Eventually visitors reach a guardhouse, where an incongruous chain stretches across the road and a sign identifies the archeological site. A central monument surrounded by sections of a wall is visible. Sand covers much of the ruin, and one can easily imagine the shifting dunes obscuring the whole edifice in a few years’ time.

Rawak profoundly impressed Aurel Stein on his arrival in April 1901. Realizing that he needed to remove massive amounts of sand before he could map the site, he sent for additional laborers to help the dozen workers in his crew. Spring windstorms blew sand into everyone’s eyes and mouths, making all physical labor trying. Working section by section, the crew eventually uncovered the central stupa, the monument designed to hold relics of the Buddha. It stood an imposing 22.5 feet (6.86 m) tall and formed the shape of a cross, with stairways on each of the four sides.

10

As the workmen shoveled away the sand, they uncovered a huge, rectangular interior wall. In addition, they unearthed the southwestern corner of an exterior wall, which originally extended all the way around the interior wall.

As worshippers walked around the monument, they proceeded through an impressive walkway, viewing the statues on both sides. Stein supposed that a wooden roof must have covered the walkway between the interior and exterior walls simply because the statues were so breakable. Some oversize statues, standing 12 or 13 feet (around 4 m) tall, depict buddhas; the smaller figures, their attendants.

The absence of wood makes carbon 14 testing impossible; one can only date the statues by rigorous stylistic comparison to other Buddhist statuary. Since the Rawak figures closely resemble the earliest Buddhist statues from Gandhara and Mathura, India, the first phase of construction at the site probably occurred in the third and fourth centuries

CE

, and a second phase followed in the late fourth and early fifth centuries, roughly the same time as the Miran site.

11

SKIRT FOR THE DEAD, SHANPULA

This, one of the largest skirts from Shanpula, measured 6 feet 2 inches (1.88 m) at the top edge, which was gathered around the deceased’s waist. The lower edge of the skirt extended a full 16 feet 6 inches (5.03 m) in length. Too unwieldy to be worn in daily life, this skirt was made specifically for the use of the dead. © Abegg-Stiftung, CH-3132 Riggisberg, 2001. Photo: Christoph von Viràg.

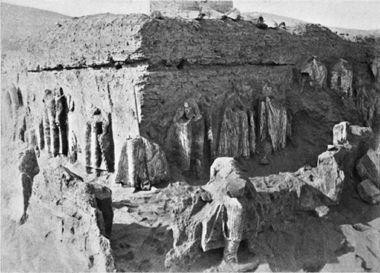

THE WALLS OF RAWAK MONASTERY OUTSIDE KHOTAN

This photograph by Stein’s crew shows the square central stupa at Rawak and the interior wall, over 3 feet (1 meter) tall. This wall, measuring 163 feet by 141 feet (50 m by 43 m), encircled the stupa, enclosing an area just under half an American football field. This wall formed a corridor that devotees used to circumambulate the stupa.

Rawak is much larger and more magnificent than any of the other stupas along the southern route (including the square stupa at Niya found by the Sino-Japanese expedition). Its size testifies to the wealth of the oasis. The Chinese monk Faxian who passed through Khotan on his way to India in 401 also remarked on the oasis’s prosperity and the extent of support for Buddhists among the populace, who, he reported, each built a small stupa in front of their doors.

Khotan had fourteen large monasteries as well as many smaller ones, and Faxian and his companions stayed in one of the large monasteries. Each year, this monastery sponsored a four-wheeled cart in a lavish Buddhist procession. Standing over 24 feet (7 m) tall, and decorated with jewels and banners, the float housed images of the Buddha and two attendants made of gold and silver. Faxian also described a new monastery built to the west of the oasis, which had just been completed after eighty years. The complex had a great hall, living quarters for monks, and a stupa standing some 66 yards (60 m) high.

12

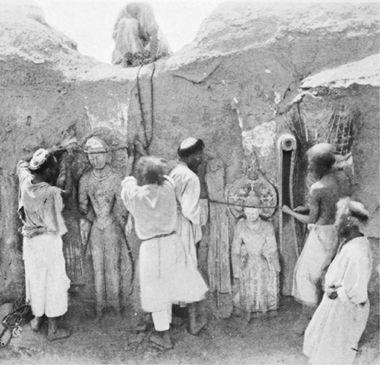

THE FRAGILE STUCCO STATUES AT RAWAK

After cleaning the sand off, Stein examined the stucco statues and concluded that they must have originally had wooden frames inside. Since the interior frames had disintegrated, the statues were too fragile to transport. Stein opted to photograph the statues and ordered his men to use ropes to prop up their heads, but the delicate heads snapped off anyway.

Faxian sometimes exaggerates the number of Buddhists or the depth of their devotion, but he does not distort the basic facts. The monasteries of Khotan were indeed wealthy. The monks of Khotan lived very differently from the Buddhists of Niya, who resided with their families and participated only occasionally in Buddhist rituals. Amply supported by donations from the king and other wealthy patrons, the Khotanese Buddhists could devote themselves full-time to study and the performance of rituals.

In subsequent centuries, with the enthusiastic support of local kings, Khotan continued to thrive as a center of Buddhist learning. Visiting in 630, the Buddhist monk Xuanzang listed the main local products: rugs, fine felt, textiles, and jade. Khotan was famous for its jade (technically nephrite), large chunks of which the inhabitants found in the riverbeds around the oasis. Khotan’s two largest rivers are named the Yurungkash (“White Jade” in Uighur) and the Karakash (“Black Jade”), and they merge north of the city to form the Khotan River. The jade found in the two rivers differs in color, and implements made from the lighter-colored Khotanese jade have been found in a royal tomb, dating to 1200

BCE

, in the central Chinese city of Anyang.

In 1900, when Aurel Stein first came to Khotan, the inhabitants were still prospecting for jade in the riverbeds. In addition, they had expanded their search to include gold and also antiquities. As he noted wryly, “‘Treasure-seeking,’

i.e.,

the search for chance finds of precious metal within the areas of abandoned settlements, has indeed been a time-honored occupation in the whole of the Khotan oasis, offering like gold-washing and jade-digging the fascinations of a kind of lottery to those low down in luck and averse to any constant exertion.”

13

These were the very men on whom Stein depended so heavily in his own excavations and explorations.

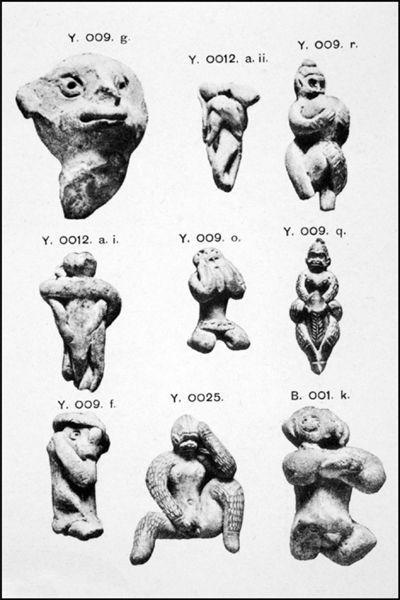

In Khotan itself, Stein purchased surface finds at Yotkan, the site of the ancient capital, but, to his frustration, no ruins survived. He did not excavate, which is puzzling, because today the visitor sees tantalizing evidence of fallen walls and buildings spread over a large area. Stein did find small clay figurines of monkeys everywhere.

14

Modern visitors can go to Yotkan, but it is more interesting to go to Melikawat, a ruin on the Yurungkash River, 22 miles (35 km) south of the city. There, multiple sand dunes sit on a barren, but evocative, moonscape occupying several square miles (10 sq km) of an ancient city lost in the dunes. One can hire a donkey cart and wander in the hills of sand—or proceed on foot. Local children offer various scavenged items for sale; tourists scan their trays of obviously manufactured fakes, hoping to spot a genuine item.

In 1901, after leaving Niya and going west for eight days, Aurel Stein found a wooden slip with the earliest evidence of the indigenous language of Khotan in Endere (modern Ruoqiang), an oasis 220 miles (350 km) to the east of Khotan. The wooden slip surfaced in the ruins of a house near a Buddhist stupa. Like the Niya documents, this slip, too, is written in Kharoshthi script, but the handwriting and the spelling are not exactly the same as those at Niya. Because of the many similarities, most scholars assume that the slip dates to the third or fourth centuries

CE

.

15