The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World (13 page)

Read The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World Online

Authors: R. Murray Schafer

Surely I am not the only one to conclude that the rhythm of hooves must have knocked around infectiously in the minds of travelers? The influence of horses’ hooves on poetical rhythms ought to yield a doctoral thesis or three, and certainly Sir Richard Blackmore once spoke of turning verses “to the rumbling of his coach’s wheels.” Some equestrian prosodist ought to be able to work the subject up from there. An influence on music is also evident. How else would one care to account for ostinato effects such as the Alberti bass, which came into existence (after 1700) when coach travel throughout Europe became practical, safe and popular? The same influence can be felt in the jigging rhythms of the country square dance, which the southern Americans call, not without reason, “kicker music.” Perhaps these thoughts are merely idiosyncratic, but I will stitch them together again when I consider the influence of the railroad on jazz and the automobile on contemporary music.

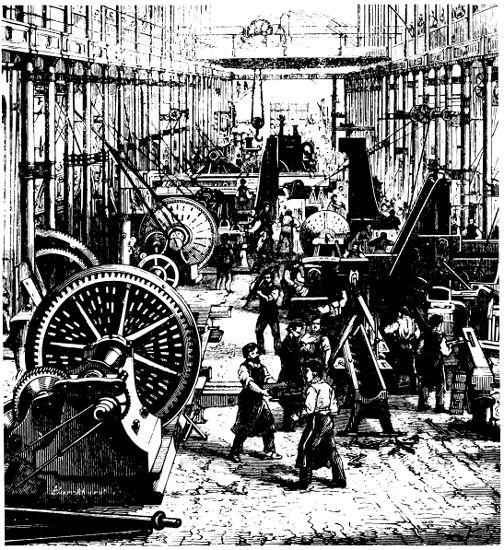

The Rhythms of Work Begin to Change

Before the industrial Revolution work was often wedded to song, for the rhythms of labor were synchronized with the human breath cycle, or arose out of the habits of hands and feet. We will later discuss how singing ceased when the rhythms of men and machines got out of sync, but it is not too early to point out the tragedy. Before this, the shanties of the sailor, the songs of the fields and workshops set the rhythm, which street vendors and flower girls imitated or counterpointed in a vast choral symphony. At first, as Gorky’s novel

The Artamonovs

testifies, the workers brought their songs to the cities willingly enough.

Pyotr Artamonov paced the building site, pulling absently at his ear, observing the work. A saw ate lusciously into wood; planes shuffled, wheezing, to and fro; axes tapped loud and clear; mortar splashed wetly onto masonry, and a whetstone sobbed against a dull axe edge. Carpenters, lifting a beam, struck up

Dubinushka

, and somewhere a young voice sang out lustily:

"Friend Zachary visited Mary,

Punched her mug to make her merry.”

Later, the workers would resign themselves spitefully to jeering at the mill. Then they would just

gather on the bank of the Vataraksha, nibbling at pumpkin and sunflower seeds and listening to the snorting and whining of the saws, the shuffling of the planes, the resounding blows of the sharp axes. They would speak in mocking tones of the fruitless building of the tower of Babel.

The industrial workshop killed singing. As Lewis Mumford put it in

Technics and Civilization:

“Labor was orchestrated by the number of revolutions per minute, rather than the rhythm of song or chant or tattoo.”

Street Criers

But this came later. Before the Industrial Revolution the streets and workshops were full of voices, and the farther south one went in Europe the more boisterous they appeared to become.

Turn your eyes upward, myriads of windows and balconies, curtains swinging in the sun, and leaves and flowers and among them, people, just to confirm your illusion. Cries, screams, whipcracks deafen you, the light blinds you, your brain begins to feel dizzy and you gulp air. You feel drawn into becoming part of the enthusiastic demonstration, to applaud, to cry “Evvive"—but for what? What is there before your eyes is nothing exceptional or extraordinary. All is perfectly calm; no deep political passion is stirring in these people. They all mind their business and talk about normal things; it is just a day like any other. It is Naples’ life in its perfect normality, nothing more.

Why do the voices of South Europeans always seem louder than their northern neighbors? Is it because they spend more time outdoors where the ambient noise level is higher? We recall that the Berbers learned to shout because they had to shout over the cataracts of the Nile.

But the streets of all major European towns were seldom quiet in those days, for there were the constant voices of hawkers, street musicians and beggars. The beggars in particular plagued the composer Johann Friedrich Reichardt when he visited Paris in 1802–3. “Usually they are not violent as they fall on one, but they hamper one and touch the heart all the more with their continuous beseeching cries and their miserable behavior.” The ubiquitous street cries were impossible to avoid. “The uproar of the street sounded violently and hideously cacophonous,” reported Virginia Woolf in

Orlando;

but this is too general. Actually each hawker had an uncounterfeiting cry. More than the words, it was the musical motif and the inflection of the voice, passed in the trade from father to son, that gave the cue, blocks away, to the profession of the singer. In the days when shops moved on wheels, ads were vocal displays. Street cries attracted the attention of composers and were incorporated into numerous vocal compositions, by Janequin in sixteenth-century France and by Weelkes, Gibbons and Dering in the England of Shakespeare’s time. The Fancies by the last three composers contain some one hundred fifty different cries and itinerant vendors’ songs. A catalogue of some of these gives a good idea of the variety of goods and services which were available in the towns of Elizabethan England:

13 different kinds of fish,

18 different kinds of fruit,

6 kinds of liquors and herbs,

11 vegetables,

14 kinds of food,

14 kinds of household stuff,

13 articles of clothing,

9 tradesmen’s cries,

19 tradesmen’s songs,

4 begging songs for prisoners,

5 watchman’s songs,

1 town crier.

The town crier preserved by Dering is clearly from before the days of the Puritan reforms. He begins with the traditional invocation “Oyez,” from the Norman French verb

oüir

, to hear.

Oyez, Oyez. If any man or woman, city or country, that can tell any tidings of a grey mare with a black tail, having three legs and both her eyes out, with a great hole in her arse, and there your snout, if there be any that can tell any tidings of this mare, let him bring word to the crier and he shall be well pleas’d for his labour.

The practice of maintaining town criers proceeded down to about 1880, or at least that is the time when their names disappear from the directories of cities like Leicester.

Public hawking was carried on also in the theaters and opera houses, as Johann Friedrich Reichardt reported from Paris.

Between the acts, hawkers enter bearing orangeade, lemonade, ice cream, fruit, and so forth, while others bring opera libretti, programs, evening newspapers and journals and still others advertise binoculars, all vying with one another and making such a commotion that one is driven to distraction. This is even worse on those days when the theatre, as is common in France, is so full that the musicians of the orchestra are forced out to accommodate extra spectators. Right after the last word of the tragedy, the hawkers push past the doors and bawl out “Orangeade, Lemonade, Glacés! marchand des lorgnettes!” and so forth, completely bereft of any music, lacerating the ears and feelings of all sensitive spectators.

Noise in the City

It will be noticed, from several of the quotations of the last few pages, that street music was a continual subject of controversy. Intellectuals were irritated by it. Serious musicians were outraged—for frequently it appears that unmusical persons would engage in the practice, not at all to bring pleasure, but merely to have their silence bought off. But resistance moved to the middle class as well, as soon as it contemplated an elevation of life style. After art music moved indoors, street music became an object of increasing scorn, and a study of European noise abatement legislation between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries shows how increasing amounts of it were directed against this activity. In England, street music was suppressed by two Acts of Parliament during the reign of Elizabeth I, but it can hardly have been very effective. Hogarth’s well-known eighteenth-century print,

The Enraged Musician

, shows the conflict between indoor and outdoor music in full view. By the nineteenth century, a by-law in Weimar had forbidden the making of music unless conducted behind closed doors. The bourgeoisie was gaining the upper hand, on paper at least. In England the brewer and Member of Parliament, Michael T. Bass, published a book in 1864 entitled

Street Music in the Metropolis

, together with a proposed Bill, designed to put an end to the abuse. Bass received a great many letters and petitions supporting his Bill, including one signed by two hundred “leading composers and professors of music of the metropolis,” who complained vigorously of the way in which “our professional duties are seriously interrupted.” Another letter, signed by Dickens, Carlyle, Tennyson, Wilkie Collins, and the Pre-Raphaelite painters John Everett Millais and Holman Hunt, stated:

Your correspondents are, all, professors and practitioners of one or other of the arts or sciences. In their devotion to their pursuits—tending to the peace and comfort of mankind—they are daily interrupted, harassed, worried, wearied, driven nearly mad, by street musicians. They are even made especial objects of persecution by brazen performers on brazen instruments, beaters of drums, grinders of organs, bangers of banjos, dashers of cymbals, worriers of fiddles, and bellowers of ballads; for, no sooner does it become known to those producers of horrible sounds that any of your correspondents have particular need of quiet in their own houses, than the said houses are beleaguered by discordant hosts seeking to be bought off.

A further communication received by Bass for his proposed bill was in the form of a detailed list of interruptions from Charles Babbage, the eminent mathematician and inventor of the calculating machine. Brass bands, organs and monkeys were the chief distractions, and Babbage came to the conclusion that “one-fourth part of my working power has been destroyed by the nuisance against which I have protested.”

Selective Noise Abatement: The Street Crier Must Go

As a result of this agitation, the Metropolitan Police Act of 1864 was passed, though the problem cannot have been immediately solved, for street cries continued to be noted until the turn of the century and later. But by 1960, the only European city in which street cries could still regularly be heard was Istanbul. When at last the legislators of European towns were able to conclude that the problem of street music had been solved, they failed to appreciate the correct reason for it. It was not the result of centuries of legislative refinement but the invention of the automobile that muffled the voices of the street cries. Then slow-witted administrations all over the world got down to designing by-laws to solve a problem that had already disappeared. “No hawker, huckster, peddler or petty chapman, news vendor or other person shall by his intermittent or reiterated cries disturb the peace, order, quiet or comfort of the public” (Vancouver, By-Law No. 2531, passed in 1938).

By the 1930s Parisian citizens were lamenting the disappearance of street criers—

si la chanson française ne doit pas mourir ce sont les chanteurs des rues qui doivent la perpetuer;

but Professor Beauty was by that time in his padded cell, which is to say that the disappearance of street music has been largely a matter of indifference to aesthetes and collectors.

The study of noise legislation is interesting, not because anything is ever really accomplished by it, rather because it provides us with a concrete register of acoustic phobias and nuisances. Changes in legislation give us clues to changing social attitudes and perceptions, and these are important for the accurate treatment of sound symbolism.

Early noise abatement legislation was selective and qualitative, contrasting with that of the modern era, which has begun to fix quantitative limits in decibels for all sounds. While most of the legislation of the past was directed against the human voice (or rather the rougher voices of the lower classes), no piece of European legislation was ever directed against the far larger sound—if objectively measured—of the church bell, nor against the equally loud machine which filled the church’s inner vaults with music, sustaining the institution imperiously as the hub of community life—until its eventual displacement by the industrialized factory.

PART TWO

The Post-Industrial Soundscape