The Spoilers (22 page)

Authors: Rex Beach

He took down his Winchester, oiled and cleaned it, then buckled on a belt of cartridges. Still he wrestled with himself. He felt that he was being ground between his loyalty to the Vigilantes and his own conscience. The girl was one of the gang, he reasonedâshe had schemed with them to betray him through his love, and she was pledged to the one man in the world whom he hated with fanatical fury. Why should he think of her in this hour? Six months back he would have looked with jealous eyes upon the right to lead the Vigilantes, but this change that had mastered himâwhat was it? Not cowardice, nor caution. No. Yet, being intangible, it was none the less marked, as his friends had shown him an hour since.

He slipped out into the night. The mob might do as it pleased elsewhere, but no man should enter her house. He found a light shining from her parlor window, and, noting the shade up a few inches, stole close. Peering through, he discovered Struve and Helen talking. He slunk back into the shadows and remained hidden for a considerable time after the lawyer left, for the dancers were returning from the hotel and passed close by. When the last group had chattered away down the street, he returned to the front of the house and, mounting the steps, knocked sharply. As Helen appeared at the door, he stepped inside and closed it after him.

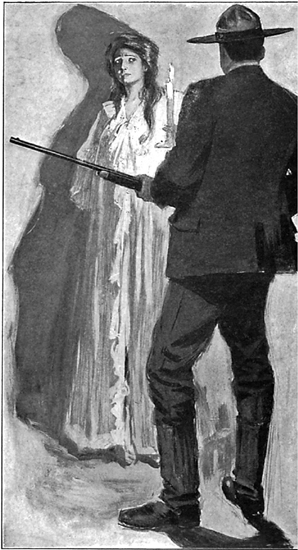

The girl's hair lay upon her neck and shoulders in tumbled brown masses, while her breast heaved tumultuously at the sudden, grim sight of him. She stepped back against the wall, her wondrous, deep, gray eyes wide and troubled, the blush of modesty struggling with the pallor of dismay.

The picture pained him like a knife-thrust. This girl was for his bitterest enemyâno hope of her was for him. He forgot for a moment that she was false and plotting, then, recalling it, spoke as roughly as he might and stated his errand. Then the old man had appeared on the stairs above, speechless with fright at what he overheard. It was evident that his nerves, so sorely strained by the events of the past week, were now snapped utterly. A human soul naked and panic-stricken is no pleasant sight, so Glenister dropped his eyes and addressed the girl again:

“Don't take anything with you. Just dress and come with me.”

The creature on the stairs above stammered and stuttered, inquiringly:

“What outrage is this, Mr. Glenister?”

“The people of Nome are up in arms, and I've come to save you. Don't stop to argue.” He spoke impatiently.

“Is this some r-ruse to get me into your power?”

“Uncle Arthur!” exclaimed the girl, sharply. Her eyes met Glenister's and begged him to take no offence.

“I don't understand this atrocity. They must be mad!” wailed the Judge. “You run over to the jail, Mr. Glenister, and tell Voorhees to hurry guards here to protect me. Helen, âphone to the military post and give the alarm. Tell them the soldiers must come at once.”

“Hold on!” said Glenister. “There's no use of doing thatâthe wires are cut; and I won't notify Voorheesâhe can take care of himself. I came to help you, and if you want to escape you'll stop talking and hurry up.”

“SHE STEPPED BACK AGAINST THE WALL, HER WONDROUS, DEEP, GRAY EYES WIDE AND TROUBLED”

“I don't know what to do,” said Stillman, torn by terror and indecision. “You wouldn't hurt an old man, would you? Wait! I'll be down in a minute.”

He scrambled up the stairs, tripping on his robe, seemingly forgetting his niece till she called up to him, sharply:

“Stop, Uncle Arthur! You mustn't

run away.”

She stood erect and determined. “You wouldn't do

that,

would you? This is our house. You represent the law and the dignity of the government. You mustn't fear a mob of ruffians. We will stay here and meet them, of course.”

“Good Lord!” said Glenister. “That's madness. These men aren't ruffians; they are the best citizens of Nome. You don't realize that this is Alaska and that they have sworn to wipe out McNamara's gang. Come along.”

“Thank you for your good intentions,” she said, “but we have done nothing to run away from. We will get ready to meet these cowards. You had better go or they will find you here.”

She moved up the stairs, and, taking the Judge by the arm, led him with her. Of a sudden she had assumed control of the situation unfalteringly, and both men felt the impossibility of thwarting her. Pausing at the top, she turned and looked down.

“We are grateful for your efforts just the same. Good-night.”

“Oh, I'm not going,” said the young man. “If you stick I'll do the same.” He made the rounds of the first-floor rooms, locking doors and windows. As a place of defence it was hopeless, and he saw that he would have to make his stand up-stairs. When sufficient time had elapsed he called up to Helen:

“May I come?”

“Yes,” she replied. So he ascended, to find Still-man in the hall, half clothed and cowering, while by the light from the front chamber he saw her finishing her toilet.

“Won't you come with meâit's our last chance?” She only shook her head. “Well, then, put out the light. I'll stand at that front window, and when my eyes get used to the darkness I'll be able to see them before they reach the gate.”

She did as directed, taking her place beside him at the opening, while the Judge crept in and sat upon the bed, his heavy breathing the only sound in the room. The two young people stood so close beside each other that the sweet scent of her person awoke in him an almost irresistible longing. He forgot her treachery again, forgot that she was another's, forgot all save that he loved her truly and purely, with a love which was like an agony to him. Her shoulder brushed his arm; he heard the soft rustling of her garment at her breast as she breathed. Some one passed in the street, and she laid a hand upon him fearfully. It was very cold, very tiny, and very soft, but he made no move to take it. The moments dragged along, still, tense, interminable. Occasionally she leaned towards him, and he stooped to catch her whispered words. At such times her breath beat warm against his cheek, and he closed his teeth stubbornly. Out in the night a wolfdog saddened the air, then came the sound of others wrangling and snarling in a near-by corral. This is a chickless land and no cock-crow breaks the midnight peace. The suspense enhanced the Judge's perturbation till his chattering teeth sounded like castanets. Now and then he groaned.

The watchers had lost track of time when their strained eyes detected dark blots materializing out of the shadows.

“There they come,” whispered Glenister, forcing her back from the aperture; but she would not be denied, and returned to his side.

As the foremost figures reached the gate, Roy leaned forth and spoke, not loudly, but in tones that sliced through the silence, sharp, clean, and without warning.

“Halt! Don't come inside the fence.” There was an instant's confusion; then, before the men beneath had time to answer or take action, he continued: “This is Roy Glenister talking. I told you not to molest these people and I warn you again. We're ready for you.”

The leader spoke. “You're a traitor, Glenister.”

He winced. “Perhaps I am. You betrayed me first, though; and, traitor or not, you can't come into this house.”

There was a murmur at this, and some one said:

“Miss Chester is safe. All we want is the Judge. We won't hang him, not if he'll wear this suit we brought along. He needn't be afraid. Tar is good for the skin.”

“Oh, my God!” groaned the limb of the law.

Suddenly a man came running down the planked pavement and into the group.

“McNamara's gone, and so's the marshal and the rest,” he panted. There was a moment's silence, and then the leader growled to his men, “Scatter out and rush the house, boys.” He raised his voice to the man in the window. “This is your workâyou damned turncoat.” His followers melted away to right and left, vaulted the fence, and dodged into the shelter of the walls. The click, click of Glenister's Winchester sounded through the room while the sweat stood out on him. He wondered if he could do this deed, if he could really fire on these people. He wondered if his muscles would not wither and paralyze before they obeyed his command.

Helen crowded past him and, leaning half out of the opening, called loudly, her voice ringing clear and true:

“Wait! Wait a moment. I have something to say. Mr. Glenister didn't warn them. They thought you were going to attack the mines and so they rode out there before midnight. I am telling you the truth, really. They left hours ago.” It was the first sign she had made, and they recognized her to a man.

There were uncertain mutterings below till a new man raised his voice. Both Roy and Helen recognized Dextry.

“Boys, we've overplayed. We don't want

these

peopleâMcNamara's our meat. Old bald-face up yonder has to do what he's told, and I'm ag'in' this twenty-to-one midnight work. I'm goin' home.” There were some whisperings, then the original spokesman called for Judge Stillman. The old man tottered to the window, a palsied, terror-stricken object. The girl was glad he could not be seen from below.

“We won't hurt you this time, Judge, but you've gone far enough. We'll give you another chance, then, if you don't make good, we'll stretch you to a lamppost. Take this as a warning.”

“Iâs-shall do my d-d-duty,” said the Judge.

The men disappeared into the darkness, and when they had gone Glenister closed the window, pulled down the shades, and lighted a lamp. He knew by how narrow a margin a tragedy had been averted. If he had fired on these men his shot would have kindled a feud which would have consumed every vestige of the court crowd and himself among them. He would have fallen under a false banner, and his life would not have reached to the next sunset. Perhaps it was forfeit nowâhe could not tell. The Vigilantes would probably look upon his part as traitorous; and, at the very least, he had cut himself off from their support, the only support the Northland offered him. Henceforth he was a renegade, a pariah, hated alike by both factions. He purposely avoided sight of Stillman and turned his back when the Judge extended his hand with expressions of gratitude. His work was done and he wished to leave this house. Helen followed him down to the door and, as he opened it, laid her hand upon his sleeve.

“Words are feeble things, and I can never make amends for all you've done for us.”

“For

us!”

cried Roy, with a break in his voice. “Do you think I sacrificed my honor, betrayed my friends, killed my last hope, ostracized myself, for

âus'

? This is the last time I'll trouble you. Perhaps the last time I'll see you. No matter what else you've done, however, you've taught me a lesson, and I thank you for it. I have found myself at last, I'm not an Eskimo any longerâI'm a man!”

“You've always been that,” she said. âI don't understand as much about this affair as I want to, and it seems to me that no one will explain it. I'm very stupid, I guess; but won't you come back to-morrow and tell it to me?”

“No,” he said, roughly. “You're not of my people. McNamara and his are no friends of mine, and I'm no friend of theirs.” He was half down the steps before she said, softly:

“Good-night, and God bless youâfriend.”

She returned to the Judge, who was in a pitiable state, and for a long time she labored to soothe him as though he were a child. She undertook to question him about the things which lay uppermost in her mind and which this night had half revealed, but he became fretful and irritated at the mention of mines and mining. She sat beside his bed till he dozed off, puzzling to discover what lay behind the hints she had heard, till her brain and body matched in absolute weariness. The reflex of the day's excitement sapped her strength till she could barely creep to her own couch, where she rolled and sighedâtoo tired to sleep at once. She awoke finally, with one last nervous flicker, before complete oblivion took her. A sentence was on her mindâit almost seemed as though she had spoken it aloud:

“The handsomest woman in the North . . . but Glenister ran away.”

IN WHICH THE TRUTH BEGINS TO BARE ITSELF

I

T was nearly noon of the next day when Helen awoke to find that McNamara had ridden in from the Creek and stopped for breakfast with the Judge. He had asked for her, but on hearing the tale of the night's adventure would not allow her to be disturbed. Later, he and the Judge had gone away together.

Although her judgment approved the step she had contemplated the night before, still the girl now felt a strange reluctance to meet McNamara. It is true that she knew no ill of him, except that implied in the accusations of certain embittered men; and she was aware that every strong and aggressive character makes enemies in direct proportion to the qualities which lend him greatness. Nevertheless, she was aware of an inner conflict that she had not foreseen. This man who so confidently believed that she would marry him did not dominate her consciousness.