The Success and Failure of Picasso (16 page)

Read The Success and Failure of Picasso Online

Authors: John Berger

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Artists; Architects; Photographers

His former friends, and especially Braque and Juan Gris, considered his new life a betrayal of what they had once striven for. Yet the problem was not simple. Braque and Gris, in order to continue as before, had to retreat within themselves. Picasso chose instead to go the way of the world. The private details involved need not concern us. What we need to know is how his spirit, his attitudes, were changed.

The change was dramatic, as you can see immediately in this portrait of his future wife in an arm-chair:

47

Picasso. Olga Picasso in an Armchair. 1917

According to Apollinaire’s distinction, Picasso has re-become an artist of the first type. He has re-acquired his prodigious skill, his uniqueness, and his ease. This particular portrait is so stuffy – an

haute bourgeoise

complete with fan in a glass case on the china cabinet – that distaste may blind us somewhat to the skill. The skill is more obvious in the drawing of

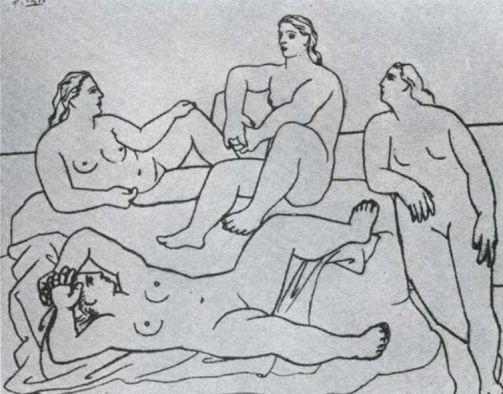

Bathers.

48

Picasso. Bathers. 1921

The legend of Picasso

as a magician now begins. It is said that he can do anything with a shape or a line. This legend is to culminate much later in the famous sequence of Picasso drawing with light from an electric torch in the film made by Clouzot and aptly called

Le Mystère Picasso.

He did not of course revert to what he had been in 1906. He never forgot the experience of Cubism. The woman lying on her back in the

Bathers

is drawn in a way that would have been impossible before 1910. And soon Picasso was to re-apply the lessons of Cubism in a far more violent and original way. But, except on the very rare occasions when he has been deeply moved, the struggle and what Apollinaire called ‘the stammering’ has gone. The prodigy has been re-born.

Picasso was now not only successful, he was also exotic. The circle in which he moved could not have accepted him on any other terms except those of exoticism. Beneath his perfectly-made dinner-jacket he wore a bullfighter’s cummerbund. For a ball given by Comte Étienne de Beaumont

he dressed as a matador. He designed three more ballets for Diaghilev. Compared with

Parade

they were conventional and romantic. One was set in Naples and the other two in ‘picturesque’ Spain.

The experience of being fěted and employed as an exotic magician, combined with the sense of isolation which has always accompanied Picasso’s awareness of himself as a prodigy, re-awoke the vertical invader. Perhaps the sense of loss he must have felt about his Cubist friends contributed to the awakening. Aware of being exiled from the one period in which he had been accepted by others as an equal, in which he felt at home, he now became more sharply conscious of his other exile from Spain.

49

Picasso as a matador. 1924

A frontal attack like

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon

was out of the question; Picasso was still enjoying his success. All that the vertical invader claimed was recognition of his origins. He had conquered but he needed to fly his own standard.

It was at this time that Picasso first began to caricature European art, the art of the museums. At first, and very gently, he caricatured Ingres.

50

Ingres. Drawing. 1828

51

Picasso. Madame Wildenstein. 1918

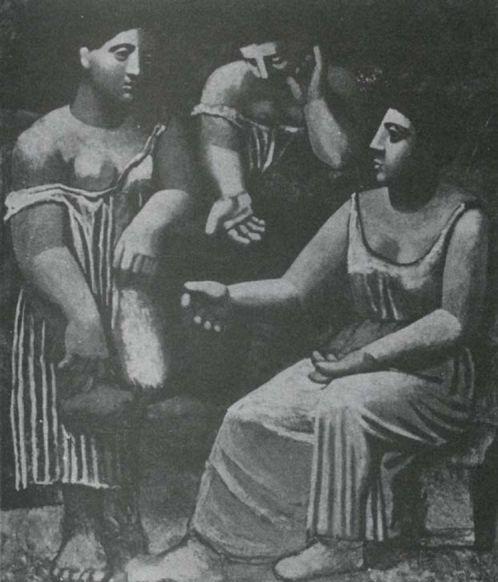

Later and more obviously he caricatured the classic ideal, as found in Greek sculpture and in Poussin.

52

Picasso. Women at the Fountain. 1921

53

Poussin. Eliezer and Rebecca (detail). 1648

The word

caricature

may give the wrong impression. Perhaps these works of Picasso are more like a performance by an impersonator of genius. The performance is too skilful to be considered a mere joke. Yet there is certainly an element of mockery.

For the vertical invader these impersonations or caricatures serve two purposes. First they prove that he can do what the masters have done: that he – who has no terms of his own – can challenge them all on their own terms. Secondly they suggest that, if this is possible, the value and honour officially given to cultural traditions may be exaggerated. If a commoner can perform as a king, where is the justification for royalty? They are not made out of disrespect for the artists concerned, but out of contempt for the idea of a cultural hierarchy.

Perhaps I should add that, although such works prove Picasso’s comparable skill, they are not as satisfying or profound as the originals, because there is a self-conscious division between their form and content. The way in which they are painted or drawn does not arise directly out of what Picasso has to say

about his subject

, but instead out of what Picasso has to say about art history. It is the limitation of

pastiche: a pastiche always has two heads. Picasso gives Madame Wildenstein the mask of an Ingres; he could have given her the mask of a Lautrec, but it would have been socially undesirable. Ingres draws Madame Delorme as he sees her. It is true that he also idealizes and formalizes her, but these formalizations have become part of his way of seeing, they are the mode of his talent’s obsession.

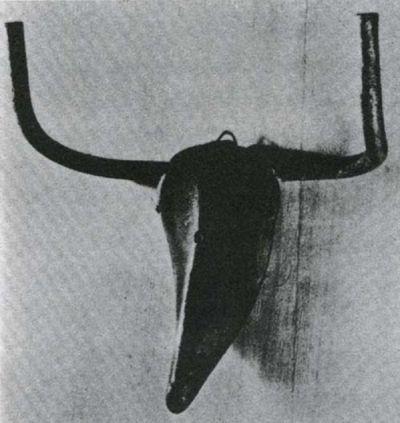

There was a second way in which the vertical invader claimed recognition. From the early twenties onwards Picasso began to make oracular statements about his art. Finding himself treated as a ‘magician’ – in the fashionable sense of the word – he began to discover within himself a more serious magical basis for his work.

The essence of magic is the primitive belief that the will can control the latent forces and spirits residing in all objects and all nature. The power to bewitch and the state of being possessed are superstitious legacies from this early belief. The Spanish

duende

is not far removed from magic. Generally speaking, some belief in magic persisted up to the stage of social development of the clan – and the clan, if not a continuing reality, was at least a memory in Spain.

Frazer in

The Golden Bough

defines magic as mistaking an ideal connexion for a real one.

Men mistook the order of their ideas for the order of nature, and hence imagined that the control which they have, or seem to have, over their thoughts, permitted them to exercise a corresponding control over things.

Magic is an illusion. But its relevance should not be underestimated in the modern world.

13

To some extent all art derives its energy from the magical impulse – the impulse to master the world by means of words, rhythm, images, and signs. Magic first led man to the beginnings of science. And now, modern science confirms, if not the practice, at least some of the concepts of magic. The concept of ‘action at a distance’, with which Faraday struggled and from which he created the concept of the field of force, was fundamental to magic. So also was the conviction that reality was indivisible. Magic offered a blueprint of a unified world in which division – and therefore alienation – was impossible. This blueprint, which had no more substance than a dream, has now become a scientific aim. Magic may be an illusion but it is less profoundly so than utilitarianism.