Read The Success and Failure of Picasso Online

Authors: John Berger

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Artists; Architects; Photographers

The Success and Failure of Picasso (17 page)

It is hard to say how conscious Picasso is of talking about his art in terms of magic. What he says is sincere; it describes what he feels when working. At the same time it emphasizes the difference between himself and those who buy his pictures and lionize him. He establishes his right to ignore a certain kind of reasoning. Instead he establishes a logic of his own through which he can express his sense of the mysterious power which he has brought with him from childhood and from the past.

I deal with painting as I deal with things, I paint a window just as I look out of a window. If an open window looks wrong in a picture, I draw the curtain and shut it, just as I would in my own room.

This is a perfect example of ‘mistaking’ an ideal connexion for a real one. Or again, expressed more abstractly: ‘I don’t work

after

nature, but

before

nature and with her.’ This is a definition of magic.

The power which Picasso possesses means that he must be granted a special licence:

It is my misfortune – and probably my delight – to use things as my passions tell me. What a miserable fate for a painter who adores blondes to have to stop himself putting them into a picture because they don’t go with the basket of fruit! How awful for a painter who loathes apples to have to use them all the time because they go so well with the cloth. I put all the things I like into my pictures. The things – so much the worse for them: they just have to put up with it.

On one level, Picasso is claiming here his right to adore blondes – in the flesh. Baskets of fruit notwithstanding, no painter has ever had to stop himself

painting

blondes! But on another level there is the implication that his passions, his will, can control ‘things’ – even against their wishes, and that by means of painting a ‘thing’, he possesses it.

He can be possessed himself, but not in the sense in which the word is understood in the Rue de la Boëtie, a fashionable street of antique-dealers and

objets d’art

, into which he moved in 1918.

The artist is a receptacle for emotions that come from all over the place: from the sky, from the earth, from a scrap of paper, from a passing shape, from a spider’s web. That is why we must not discriminate between things. Where things are concerned there are no class distinctions.

This view of himself as an artist – the artist as receptacle – incidentally confirms how Picasso fits again into Apollinaire’s first category. It also stresses the difference between his unified world of magic and the life around him in a class society. ‘Where things are concerned there are no class distinctions’ would make no sense to an antique-dealer – for him the very opposite is true. But it is a prerequisite for magic.

The primitive, magical bias of Picasso’s genius is not only evident in his statements about art: he performs quasimagical ceremonies as well. Here is an account by

Roland Penrose of Picasso making

pottery.

Taking a vase which had just been thrown by Aga, their chief potter, Picasso began to mould it in his fingers. He first pinched the neck so that the body of the vase was resistant to his touch like a balloon, then with a few dexterous twists and squeezes he transformed the utilitarian object into a dove, light, fragile, and breathing life. ‘You see,’ he would say, ‘to make a dove you must first wring its neck.’

14

Of course this is a game. But play and magic are perfectly reconcilable. (All young children live !through a phase of believing that the world is governed by desire or will.) And what is remarkable is how we feel Penrose, who is by no means an unsophisticated man, falling under the spell of this magic. He is induced to say that the dove breathes life! He has seen the dead turned into the living.

Picasso began to play with such transmutations in the early thirties and spasmodically he has continued up to the present. He takes an object and turns it into a being. He has turned a bicycle saddle and a pair of handlebars into a bull’s head. He has turned a toy car into a monkey’s face, some wooden planks into men and women, etc.

54

Picasso. Bull’s Head. 1943

In the case of the

Bull’s Head

, Picasso has not changed the form of the saddle and handlebars at all. He has scarcely touched them. What he has done is to

see

their possibility of becoming an image of a bull’s head. Having seen this, he has placed them together. The seeing of this possibility was a kind of naming. ‘Let this be a bull’s head,’ Picasso might have said to himself. And this is very close to African magic.

Janheinz Jahn, in

Muntu

,

15

his study of African culture, writes:

It is the word,

Nommo

, that creates the image. Before that there is

Kintu

, a ‘thing’, which is no image, but just the thing itself. But in the moment when the thing is invoked, appealed to, conjured up through

Nommo

, the word – in that moment

Nommo

, the procreative force, transforms the thing into an image … the poet speaks and transforms thing-forces into forces of meaning, symbols, images.

Picasso is an intricately complex character. There is a part of him, cunning as any Rasputin, which exploits ‘magic’ in response to his success as a ‘magician’. There is another part of him which uses it to procure himself licence as a public figure and to defend his independence. Yet another part is governed by sympathies and needs which are unusually close to the point where art really did emerge from magic.

We traced the influence of the vertical invader in Picasso’s choice and treatment of subjects in the period before Cubism, before he became open to the influence of friends. We can see the same influence in his later work, when he was once again isolated.

In the late twenties Picasso became disillusioned with the

beau monde.

He retreated into himself. During the thirties his work was mostly introspective. (

Guernica

, as we shall see later, is a highly introspective work and only the political uses to which it was rightly put have confused people about this.) The imagery of this period is Spanish, mythological, and ritualistic. Its symbols are the bull, the horse, the woman, and the Minotaur.

At this time Picasso was involved in a passionate love-affair, and many of his best works were sexual in inspiration and content. In some of these he clearly identifies himself with the Minotaur.

55

Picasso. Bull, Horse, and Female Matador. 1934

56

Picasso. Sitting Girl and Sleeping Minotaur. 1933

The Minotaur represents the animal in the captivity of an almost human form; it also represents (like the fable of Beauty and the Beast) the suffering which is caused by aspiration and sensibility being rejected because they exist in an unattractive, that is to say untamed, uncivilized body. Either way, the Minotaur suggests a criticism of civilization, which inhibits him in the first case, and dismisses him in the second. Yet, unlike the Beast, the Minotaur is not a pathetic creature. He is a king. He has his own power – which is the result of his physical strength and the fact that he is familiar with his instincts and has no fear of them. His triumph is in sexual love, to which even the civilized ‘Beauty’ eagerly responds.

The emphasis of Picasso’s work did not change again until the end of the Second World War. Naturally, between 1930 and 1944 he painted many different subjects and employed different styles. But all the great works of this period – and in my view it is the period when, the Cubist years excepted, he produced his best paintings and sculpture – share the same preoccupation: a preoccupation with physical sensations so strong and deep that they destroy all objectivity and reassemble reality as a complement to pain or pleasure. Put like that, it may sound as though these works are Expressionist. They are not.

Expressionism, as in

Egon Schiele’s

Self-Portrait

, is concerned with distortions which reflect violent emotions –

Angst

, awe, pity, hatred, etc. Expressionism is produced by frustration.

57

Schiele. Seated Male Nude (self-portrait). 1910

The paintings we are considering by Picasso are concerned with distortions which reflect sensations – sexual desire, pain, claustrophobia, etc. They are the result of a kind of self-abandonment.

58

Picasso. Nude on a Black Couch. 1932

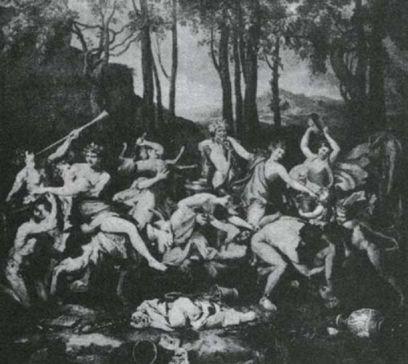

Perhaps the best way of making the point clear is by another comparison. In 1944, on the day Paris was liberated, Picasso painted a variation of Poussin’s

The Triumph of Pan.

It is not one of Picasso’s best paintings, and probably he simply painted it to fix his mind on something whilst he waited for news in his studio. But because the composition of the two pictures is so similar, we can distinguish all the more sharply the way Picasso’s imagination was used to working.