The World at War (77 page)

Authors: Richard Holmes

Their prey – a burning freighter sinks in the Indian Ocean.

The Japanese surrender delegation aboard USS

Missouri,

2 September 1945. Interviewee Toshikazu Kase stands third from the right, holding a briefcase.

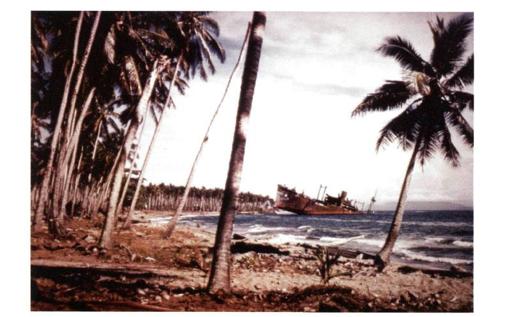

Beached Japanese transport at Guadalcanal.

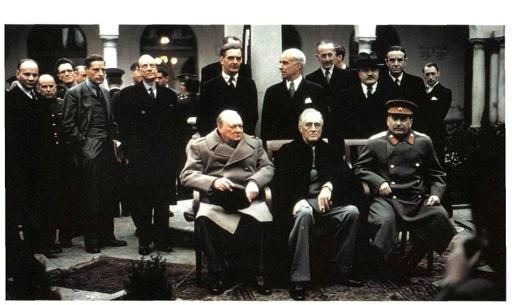

The victorious Big Three at Yalta. Roosevelt was dying, Churchill was exhausted and only Stalin seemed eternal and indestructible. Churchill had planned to stay on in this resort after the meeting but was so dejected by the talks that he told his staff to get him away from 'this Riviera of Hades'.

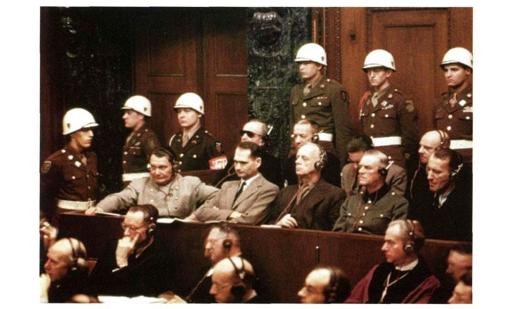

Hitler's Gang on trial at Nuremberg, 1945–46. Luftwaffe Chief Hermann Goring, Former Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess, Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and Senior SS Leader Ernst Kaltenbrunner sitting in front of Admiral Karl Dönitz (in dark glasses), his predecessor Admiral Erich Raeder, Hitler Youth Leader Baldur von Schirach and Labour Minister Fritz Sauckel.

indicate that our leaders underestimated the striking force of the Anglo-American Army that invaded Europe. We got back a good piece of western Austria which had been occupied by the Soviets. I can only say that I think, even from the Soviet point of view, that the division of Germany was regarded primarily as a division intended to keep the troops separate. I don't know when the Russians finally came to the conclusion that they were going to divide Germany.

ANTHONY EDEN

We did discuss with Russians at one of our meetings the possibility of the percentage authority we should regard the other as having in certain countries. The Americans didn't like the idea; it may seem reprehensible now and yet it was practically the only thing we could do and we thought it right to concentrate on those countries where we could. For geographical reasons in a country like Bulgaria, a Slav country, or Romania, which we couldn't reach, or Hungary, which was an enemy power, Churchill thought and I agreed with him that we could not attempt to have more than a limited influence there. So far as Greece was concerned the Russians did play fairly, and when the Greeks were fighting in Athens at Christmas 1944 and Churchill and I went out there, the Russian military representative came to the conference which we held and sat there with his gilded epaulettes, facing the local Communists, and he had quite an effect. So they did fulfil their part of the bargain so far as concerned Greece. And I am not at all repentant about the arrangement we made. Without it we couldn't have intervened as much as we did in Greece and give the country a chance not to fall under Communist rule, which Stalin might otherwise have required to be established there.

*78

CHARLES BOHLEN

In the first place during the war it was very difficult to predict Soviet policy; on the other hand there was no way of telling definitely what effect the association with Western Powers during the war, in some form of cooperation, might have had on Soviet thinking. It seemed to be an idea that three powers would consult whenever there was any problems in regard to the occupied areas and I was surprised that the Russians bought it so easily. Whether or not Stalin had in mind the famous deal with Churchill of 1944 with percentage of influence, all I can say is that it never came up at all in any form. Roosevelt knew about it, but there was never any reference to it, at least as far as we were concerned, with the Russians. But it's conceivable that Stalin was operating to some extent on what was expressed in that piece of paper.

ANTHONY EDEN

Latterly FDR was a sick man, no question of that. When Churchill and I met him at

Malta, where we'd hoped to have discussion, we were looking forward to meeting FDR when he arrived in this splendid battle cruiser in a wonderful dramatic scene. But when he came to talk – nothing. His daughter whirled him away after dinner and said, 'Now, father, it's your bedtime.' And he was sick but also I think there was this feeling that Roosevelt had, that some Americans had, they didn't want to be ganging up with us before they met the Russians. I'm sure it was a mistake, because any dictatorship in my experience functions better when those it's dealing with are ganged up. At any rate there was one of our difficulties, both that Roosevelt was sick and there was no preparation between us.

ALGER HISS

Director of the Office of Special Political Affairs, Yalta participant

There was no doubt there was a mood of euphoria. The war was going well in the West, the Russians were scoring victories. We rendezvoused with the British delegation at Malta so we got our ducks in a row before we talked to the Russians for a tripartite meeting of Allies. This, looking back on it, was a little strange, but it seemed perfectly normal at the time. The general attitude, in spite of the indications, was not edginess but distance – by the usage of 'we' and 'they', 'they' being the Russians. In spite of what that indicates there was a sense of unity in the curve of the whole development of Roosevelt's foreign policy since 1933. Yalta was the culmination of Roosevelt's policy – after all the United Nation as a term had been coined long before that. There was a belief, at least on Roosevelt's part, that coexistence was feasible, necessary and desirable. In the intemperate discussions that have come up about Yalta, the idea that nobody could trust the Russians to agree to come to lunch at a time they said was not present at that time. My experiences in all the negotiations I had with them, at San Francisco and again in London when United Nations had its first meeting, was that they were stiff bargainers, but when agreement was reached they were quite meticulous in sticking to the words of the agreement. This had some significance when we come to talk about the terms of the Yalta agreement. It was not my experience with them that they openly, cynically, welshed in any particular kind of phase – they stuck to what had been agreed to, so the real question is what was agreed to? Provisions were ambiguous so they had in their minds the right to interpretations, just as they thought we might have slightly different interpretations, which for me is the gist of the Polish part – the most difficult part of the Yalta agreement as far as the United Nations was concerned. We hammered that out in pretty considerable detail. Concessions were made to us both by the British and the Russians, and it was our show, we were the hosts. So Yalta did represent the culmination of the Roosevelt policy and there was great euphoria. There was a great deal of suspicion, I'm speaking for our side – I don't know about the Russian attitude, I would assume they were as capable of suspicion as we.

AMBASSADOR HARRIMAN

The whole myth of Yalta is that Churchill and Roosevelt sold out to Stalin. The argument was that in areas which the Red Army would occupy as they drove the Nazi forces back into Germany, Stalin was in control and there was nothing that Churchill or Roosevelt could have done physically except try to persuade Stalin. They agreed to nothing except they insisted there should be free elections, that people would be allowed to take their own part. There was an agreement about boundaries but the fundamental principle was that Poland and other countries should be free. Roosevelt's health in my opinion did not play a major role. It's perfectly true that he was weak – he was not able to work long hours, long conferences tried him, he stayed in bed in the mornings – but he took care of himself, he trained himself. These were subjects which he had been considering over several years and he had them fully in mind and he never gave in on anything that he wasn't ready to give in on. So I think there's very little in the fact to justify those who say his health played an adverse role. He was ill, he was a tired man, but a man of great courage and determination.

CHARLES BOHLEN

At the time the Red Army was in occupation of almost all of eastern Europe and most of the Balkans and therefore I think we learned there that wherever the Red Army was they would install a Sovietised system and there was just no argument about it. We did the very best we could on Poland. The British felt very strongly about it, having gone to war on behalf of Poland in 1939, and, although less so, we felt fairly strongly because of the large numbers of Poles in the United States who have intense interest to what happens in their country. Other aspects which are frequently overlooked came out more in favour of the Western side. The voting formula for the Security Council was adopted and also, largely due to the efforts of Mr Churchill backed by President Roosevelt, France obtained a zone of occupation and a seat on the Control Council. Stalin was very much opposed to that. You could tell when he was really worked up about something because he'd got up from his chair and walk up and down behind it several times in the discussion of whether France should have a zone or a seat on the Council.

ALGER HISS

My function was primarily as a technical assistant to Secretary of State Stettinius and to the President on matters relating to the United Nations. We'd corresponded back and forth with Great Britain and Russia about the things left unsaid, particularly the veto power, and we thought we were close to an agreement which could be reached at Yalta. In addition, I served in the Far Eastern Division before I started with United Nations affairs and so I was an extra in case Far Eastern policy questions came up. We had Bohlen and Freeman Matthews on such matters, and I guess that was the team. Harriman of course came, also expert not only on Soviet matters but on Europe generally; we were a pretty small team. I was concentrating on the United Nations; I could be fairly objective about the Polish and other issues. All of us went over all the papers together beforehand. This was a time when position papers were beginning to be popular and we had a session at Marrakesh with Mr Stettinius when we made him do his homework. I left out Harry Hopkins – I can see Harry's gaunt figure and face as we sat round the big table at plenary sessions. Bohlen sat on the President's left because he was interpreter. Stettinius sat on his right, behind was Harry Hopkins. Matthews and I were huddled in the remaining space in the background with papers in front of us, and occasionally whispering, occasionally passing notes. And there were pauses for consultation. In the mornings the hard work was done by the Foreign Ministers. All the plenary sessions were held at Lavadia Palace where President Roosevelt was, not because of his illness but because he was the only Chief of State – the others were merely heads of government, so it was protocol as well as convenient. We would try to hammer out in the morning sessions, the three Foreign Ministers and their staff, and after each session it was the duty of the technicians, Gladwyn Jebb and Pierson Dixon were my opposite numbers on your staff, working out the text of what had been agreed to be submitted to the plenary session.

*79